After our previous day’s walking on the Snowies Alpine Walk from Charlotte Pass Village to Perisher via Porcupine Rocks, we were keen to check out another new section. This time we settled on the new nine kilometre walk from Charlotte Pass to Guthega village. A top day beckoned. Clear skies, maximums hovering around 21o C and an alpine ramble with my walking friends Joe, Chris, Neralie and Garry.

by Glenn Burns

The BOM had issued a heatwave warning in its Snowy Mountains forecast. But for this quintet of Queenslanders the threatened 21o C maximum was just so. Not too hot, not too cold.

Snowies Alpine Walk

In 2018 construction started on the Snowies Alpine Walk. The NSW Government boasted it would deliver ‘ a world-class, multi-day walk across the alpine roof of Australia in Kosciuszko National Park.’

This 55 kilometre, 4 day walk, on Ngarigo Country, connects the existing Mt Kosciuszko-Main Range walk with three new sections. Namely, Charlotte Pass to Guthega Village; Charlotte Pass Village to Perisher Village via Porcupine Rocks and, as of 2024, the still incomplete section from Perisher Village to Bullocks Flat in the Thredbo River Valley.

After a top day of alpine walking yesterday from Charlotte Pass to Perisher, life on the track was on the up and up. An uneventful drive, with Joe at the wheel, from our digs at Sawpit Creek, delivered us to Charlotte Pass (1840 m).

Bang into an unexpectedly biting wind. Someone had neglected to clock the forecasted 50 kph wind gusts. So with the wind chill effect, the ambient temperature was pretty cold. And this was mid-summer, Australia. As my old walking pal Brian was apt to say: ‘strong enough to blow a brown dog off its chain’. We pulled on an extra layer.

Pleistocene Glaciation in Kosciuszko National Park

If you had been standing at this very spot some 60,000 years ago, in the frozen depths of the last Pleistocene ice age, the scene in front of you would have been vastly different.

You would have gazed across a panorama of snow and ice. Rivers of ice poured out from ice-filled glacial bowls on the south east flanks of Mt Lee, Mt Clarke, Carruthers Peak, and Mt Twynam. The current valleys of Club Lake Creek, Blue Lake Creek, Twynam Creek would be brimming with glacial ice grinding bedrock to a pulp on its way to join the major valley glacier in the Snowy River.

In fact, it is possible that your perch at Charlotte Pass would have been covered by a mass of abrading Snowy River glacial ice pushing over this interfluve into the neighbouring Spencers Creek valley. Or so some geologists hypothesise.

Back then temperatures would have been much colder. The minimum temperature today was 12o C. 17,000 years ago it would have been at least 5 to 8o C lower.

In Kosciuszko there is evidence of at least two distinct glaciations. The Early and Late Kosciuszko glaciations. The Early Kosciuszko Glaciation consisted of a single major advance at approximately 60, 000 years ago called the Snowy River Advance. This was the most extensive advance with later advances less extensive.

Geologists tell us that the Snowy River glacier probably extended as far downstream as Illawong Hut. Possibly further. There is evidence of glacial debris downsteam at Island Bend, discovered during surveys for the Snowy Mountain Scheme.

The Late Kosciuszko glaciation consisted of three smaller glacier advances, starting about 32,00 years ago: Hedley Tarn Advance (32,000 years ago), Blue Lake Advance (19,000 years ago) and Mt Twynam Advance (17,000 years ago).

The systematic search for evidence of glaciation in Kosciuszko got seriously under way in 1901. A scientific party of Professor T.W. Edgeworth David (geologist), Richard Helms (zoologist and botanist), E.F. Pittman , and F.B. Guthrie (Professor of Chemistry) found incontrovertible evidence of the action of glacial erosion and deposition:

- striated rocks and boulders

- erratics

- terminal and lateral moraines

- roches moutonnees

- cirques

- tarns

- glacial polishing of rock surfaces

- truncated spurs

- U-shaped valleys

- abraded interfluves

The Kosciuszko Plateau has been now been free of of glaciers for about 15,000 years. In addition to the glacial landforms mentioned above, the observant bushwalker can find ample evidence of periglacial landforms over much of the higher country. Some easily identified of these landforms include blockstreams, solifluction terraces and thermokarst ponds.

Meanwhile, back in the Anthropocene, the Snowies Alpine Walk (SAW) from Charlotte Pass initially heads downhill on the paved NPWS vehicular track towards the Snowy River. Some 500 metres of descent will deliver you to a junction and noticeboard trumpeting the start of the walk to Guthega village. We executed a hard right onto the SAW path.

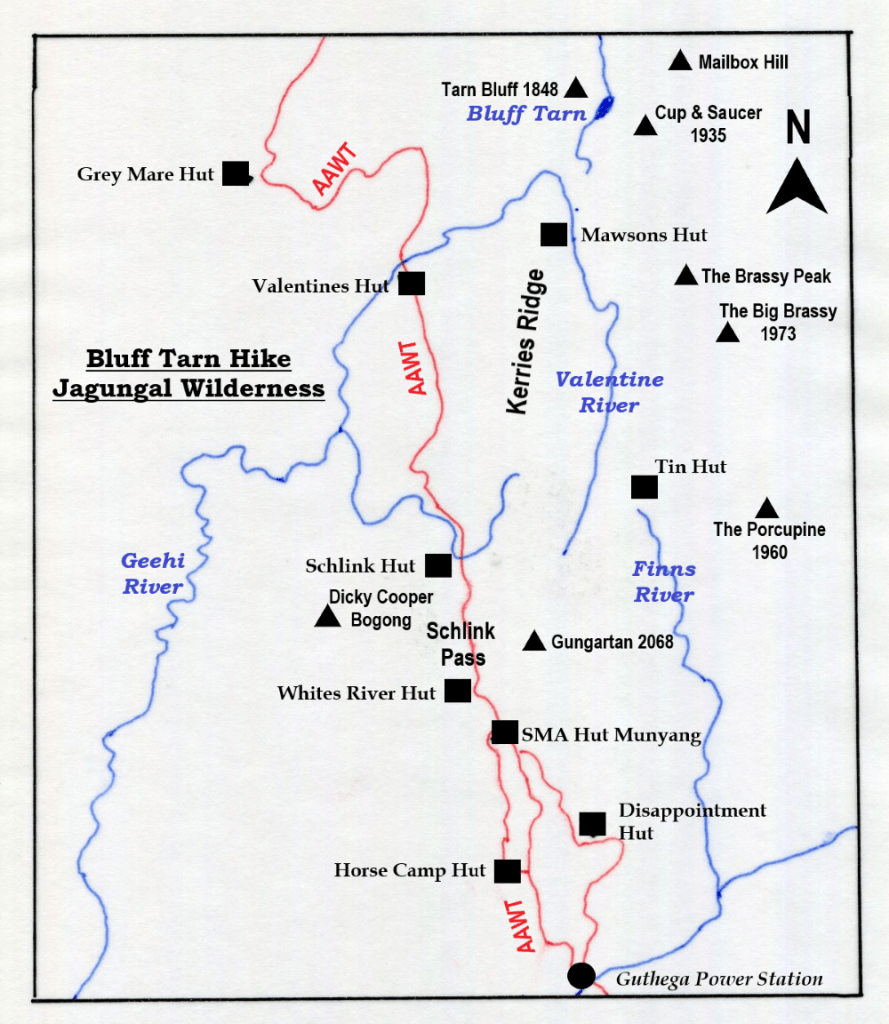

Map of Snowies Alpine Walk: Charlotte Pass to Guthega Village.

Here the SAW parallels the Snowy River on its eastern bank, winding around Guthrie Ridge on the 1700 m contour before dropping to Spencers Creek and the Snowy River at Illawong Hut. The final part of the day’s walk picks up the old Illawong-Guthega bushwalker’s pad to fetch up at Guthega Village, some nine kilometres from Charlotte Pass.

Back in the Day… 2009… Guthrie Ridge.

But, back in the day, in 2009, a 17 kilometre walk from our camp on Strzelecki Creek under The Sentinel to Charlotte Pass thence to Illawong Hut via Guthrie Ridge was more of a challenge. We set off with a brilliant off-track alpine ramble from Strzelecki Creek to Charlotte Pass via Carruthers Peak, Mt Northcote, Mt Clarke and the Snowy River Crossing.

Once at Charlotte Pass we swung off-track again to climb Mt Guthrie (1920 m). The usual suspect had cooked up this feral route that followed the spine of Guthrie Ridge (1900 m) and then descended to an overnight bivvi at the junction of Twynam Creek and the Snowy River. Close to Illawong Hut.

Mt Guthrie and Guthrie Ridge were named by Richard Helms for his friend F.B. Guthrie, Professor of Chemistry.

My peak bagging companion had hinted at another exceptional alpine stroll to cap off what had been, so far, a matchless day of hiking. A mere two and a half kilometres or a one hour leisurely amble along the spine of Guthrie Ridge would deliver us to our campsite on the junction of Snowy River and Twynam Creek. Fun times.

Mid afternoon, on a steep mountainside, high above the valley floor three beleaguered peak baggers pushed wearily through the tangle of granite boulders and scratchy mountain peppers, Kunzeas, Epacris and snow gums that lay between them and the day’s end. Route wise, a bad call.

But I was resigned to this stuff. Situation normal when walking with my bush-bashing, peak bagging buddy Brian. He claimed it was just the price we had to pay for a very satisfying and bludgy morning’s walk. Finally, we staggered in just on dusk. The campsite made it all worthwhile. We set up on a springy snow grass ledge… lulled to sleep by the riffling Snowy River. All was well in my little slice of bushwalking paradise and all is forgiven Brian.

The new Snowies Alpine Walk.

After mulling over this previous cross country experience I gave thanks for the newly minted super SAW highway. Cortan steel elevated boardwalks, rock-armoured track surfaces and dry boots compliments of a high suspension bridge over Spencers Creek. A speedier passage than taking that infernal high road along Guthrie Ridge. But nowhere near as interesting.

The track took us initially over another of those eyesore Cortan steel boardwalks much favoured in Kosciuszko National Park. But I admit they do an excellent job of protecting the low heath and snow grasses below.

Eventually the track leaves the low heath and climbs on its granite pavement ever upward through snow gum woodland. As did Garry. Left us, that is. We found him, as I expected, propped on a log in a bower of snow gums. The ideal morning tea stop.

Snow gum woodland, invariably, is clothed in a dense scrubby understorey of beastly spikey undergrowth like Bossiaea, Epacris, Hakea, Grevillea, Oxylobium, and Kunzea . Here’s where those weird knee-length canvas gaiter things worn by Australian bushwalkers are a brilliant piece of kit.

The low growing snow gum woodland is found above 1500 metres and is dominated by snow gums or white sallee ( Eucalyptus pauciflora).

The snow gum zone is found extending down to the lower levels of winter snowfall and is the only tree to grow above 1500 metres. Above this woodland zone the landscape transitions suddenly into the true alpine zone of heathland, grassland and bogs.

The undergrowth is called heath and can be waist-high with tough whippy branches to withstand the weight of snow (and, hopefully, bushwalkers) without breaking. Throw in the odd torpid highland copperhead and pit-fall traps of wombat and bunny burrows and hiking through this scrub quickly losses its appeal.

Fortunately, the new super SAW highway saved us from having to thrash through that stuff.

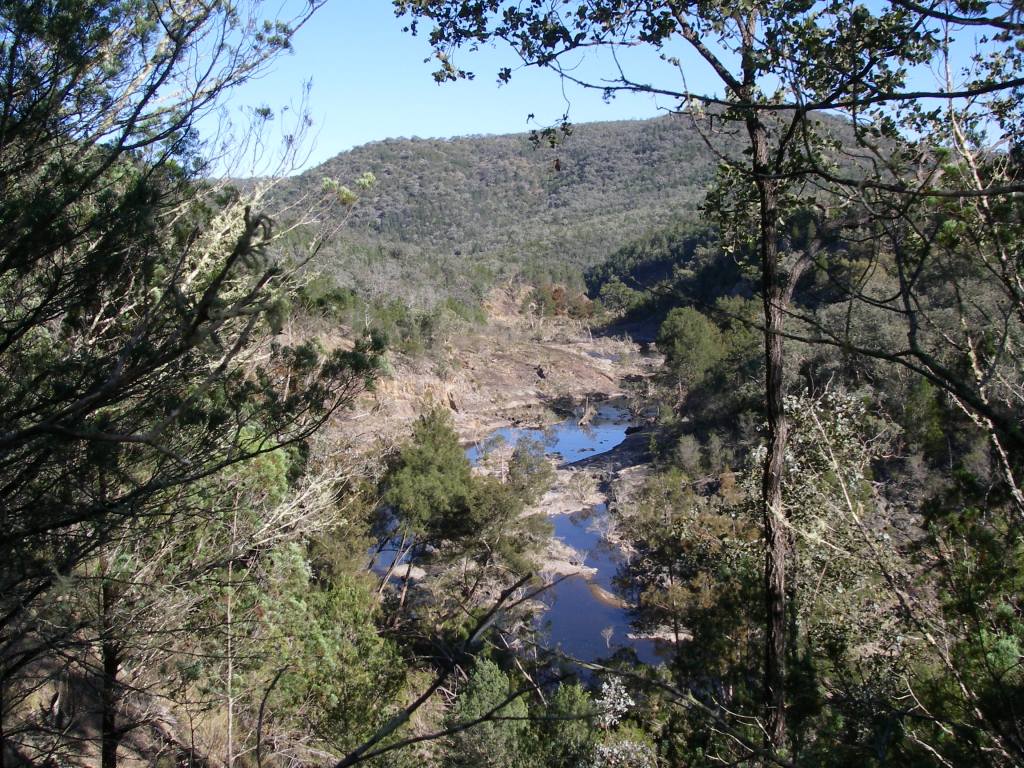

Much of the SAW walk parallels the Snowy River which flows NNE downstream towards Guthega Pondage. It is joined on its western bank by the south east flowing drainage lines of Blue Lake Creek, Twynams Creek and Pounds Creek.

These creeks have their headwaters along the highest parts of Australia’s Great Dividing Range: Carruthers Peak (2010 m), Mt Twynam (2196 m), Mt Anton ( 2010 m) and Mt Anderson (1997 m). The Main Range peaks all visible from this section of the SAW.

Today’s walk provided expansive and unimpeded views down the nearly straight Snowy River Valley. Its side slopes planed back by late Pleistocene valley glaciers. Glacial valleys all over the world typically exhibit these truncated spurs and U shaped valleys.

Some 4.5 kilometres after the track entrance our path left the snow gum woodland and descended across low heath covering a gently rounded spur at the intersection of the Snowy River and Spencers Creek. An abraded spur, ground down during the Pleistocene by the Snowy River and Spencers Creek valley glaciers.

Joe and I caught up Chris and Neralie just short of the Spencers Creek suspension bridge. They were magging with two walkers travelling in the reverse direction. Uphill to Charlotte Pass. I’m not sure of the rationale for doing this section uphill, but many people do. Meanwhile, Garry was last seen as a distant speck beetling toward Illawong Hut.

The SAW track builders had thoughtfully provided a nifty suspension bridge consisting of a steel mesh plank and handrails to usher walkers safely across Spencers Creek. Built in 2021 it is said to be, in terms of its location, at 1627 metres of altitude, the highest suspension bridge in Australia .

Meanwhile Garry had escaped the wind by taking refuge at the side of the hut. Just don’t turn up here in a serious blizzard. You will find the inn door locked, as we did. An unusual arrangement for high country shelters. But this is because Illawong is the only private lodge outside the main ski resorts.

But, to be fair, the illustrous Illawong Ski Tourers have thoughtfully provided a sealed crawl space for midgets under the hut for just such an emergency. And, they have thrown in as a goodwill gesture, a snow shovel to dig yourself out or in. Once out of your blizzard, don’t try to sit up. The upside is that you are safe and don’t have to share the under floor space with assorted snakes, wombats and other creepy-crawlies.

Illawong Hut

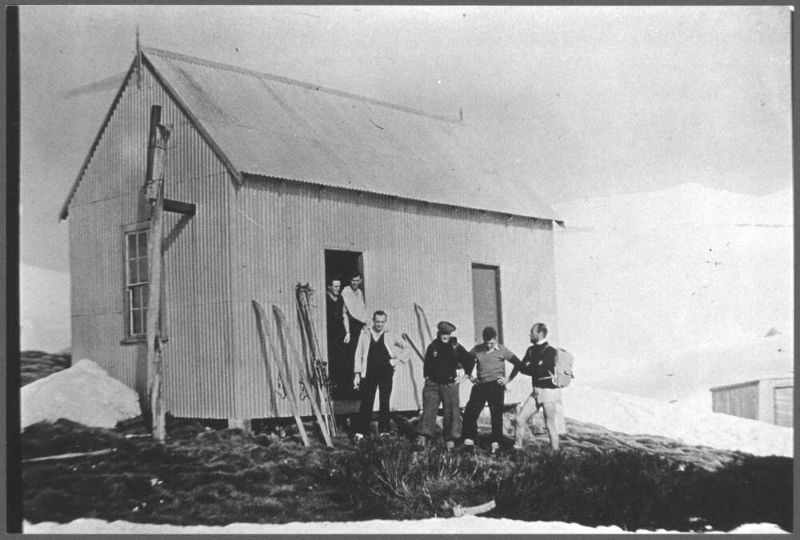

Illawong, also known as Pounds Creek Hut and Tin Hut No1, was constructed in the summer of 1926-1927 as a shelter hut. Illawong is said to mean ‘view of the water’. A basic two roomer/four bunks, it was built by the NSW Tourist Board to assist Dr Herbert Schlink in his first Kiandra to Kosciuszko ski crossing during the winter of 1927.

After construction it was used for early ski touring, summer bushwalking and by mountain cattlemen. At the time only two other buildings existed in the high country: Betts Camp and Kosciusko Hotel.

In 1955, John Turner of the Ski Tourers Association brewed up a plan to convert Pounds Creek Hut into a ski lodge. A year later, in 1956, the Kosciuszko State Trust gave permission for the hut to be extended to become a private ski lodge managed by Illawong Ski Tourers.

The conversion was a bit of mission for lodge members. No helicopter lifts in those days. All materials and food supplies had to carried in. Though some ingenious work-arounds were dreamt up. Klaus Hueneke in his first-rate tome: Huts of the High Country provides this description:

” Over the next two years members, friends and passersby spent endless summer days and occasional premature wintry ones carrying, rowing, pushing and dragging materials to site. “

And this:

” Rowing the materials up Guthega Dam was a new twist to mountain transportation and not without incident… boat trips took on ice floes, wind driven sleet and polar wombats! The final leg was considerably aided by a sled and the muscle power of Mick, a horse from the Chalet. Unfortunately he had only two speeds – stop and run like hell. “

Those enterprising Illawongians weren’t finished yet. Over the years the Lodge was spruced up with a septic tank, electric lighting, a gas cooker, a refrigerator, a hot water service, decent mattresses, carpets and a phone. A veritable home away from home. My membership application is in the mail.

Members also designed and built the flying fox over Farm Creek and the suspension bridge over the often raging Snowy River. For this latter feat all skiers and bushwalkers wanting to access the Main Range should give them fulsome thanks. Two earlier bridges had been swept away before a decent one was installed in 1971. The final version was designed and built by one Tim Lamble and assembled with the help of the NPWS helicopter.

Tim, incidently, is also the author of my favourite piece of cartographic art: the Mt Jagungal and The Brassy Mountains 1:31680 map.

Illawong Hut has been placed on the National Heritage Register, the National Trust (NSW) Register and NPWS Historic Places Register. Its NPWS citation reads:

” Illawong Hut is one of the most historically significant huts in the park, being a rare remnant of early 20th century NSW Government Tourist Bureau efforts to promote alpine tourist recreational activities.”

For good measure the Farm Creek flying fox and the Snowy River suspension bridge are also on the register.

With little over two kilometres to Guthega my friends had scarpered in a cloud of dust. The upgraded SAW track follows the old bushwalking pad between Illawong and Guthega. It skirts around the southern bank of Guthega Pondage. This pondage, a tunnel and Guthega (Munyang) hydro power station were built as part of the Snowy Mountains Scheme in the early 1950s.

Munyang (Guthega) Hydro Power Project

This Munyang (Guthega) project area is the start of many of my favourite walks in Kosciuszko.

And it is also the start of the first major project of the Snowy Mountains Scheme in 1951. The tender was awarded to a Norwegian firm, Ingenior F. Selmer. A serious player in global dam and hydro construction. The bulk of the workers were Norwegians (450, mainly labourers) from the rural areas of the Arctic Circle.

On the 21 February 1955 , only a few weeks behind schedule, electricity flowed from Munyang.

The word Munyang or Muniong derives from local aboriginal people. When camped on the Eucumbene Valley, they would point to the snow covered Main Range and repeat the word ‘Munyang’ or ‘Muniong’ . Said to mean ‘big’ or ‘high mountain’. Also ‘big white mountain’.

If you want to read more about the fascinating people and places of the Snowy Mountains Scheme, I can highly recommend Siobhan McHugh’s: ‘The Snowy, a History.‘

Nearing the end of our walk, the SAW crosses Farm Creek via a metal bridge then climbs to Guthega Village. No need to risk life and limb on the the rusty old flying fox still there. Fortunately, it has been padlocked by some kill-joy to discourage thrill seekers like my walking companions.

At the still to be completed track exit, rangers were busy fiddling around sorting out signage. Here we had views over the waters of Guthega Pondage, the dam wall and the intake for the tunnel to the top of the Munyang penstocks.

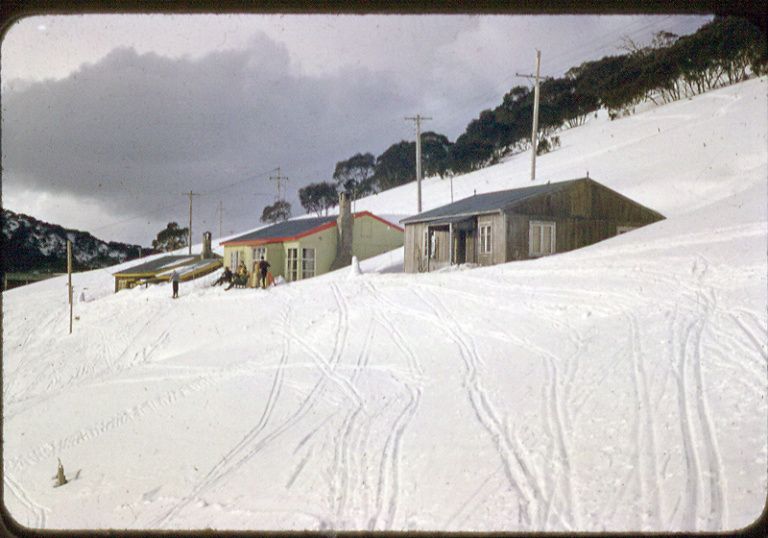

Guthega Ski Village or Little Norway

Guthega village did not exist before 1950. The only building in the area was our old friend Illawong Hut. In 1951 when the Norwegian company Selmer started construction on the first major project of the Snowy Mountains Scheme , their construction camp became known as ‘Little Norway’ as it housed the largest number of Norwegians living outside of Norway at the time.

When Selmer returned to Norway in 1954, at the end of their contract, they took most of their construction camp with them, leaving just three huts. These huts kick-started the modern day Guthega Ski Resort.

The huts were scooped up for peanuts in 1955 by SMA Cooma Ski Club, YMCA Canberra Ski Club and Sydney University Ski Club. The village now sports private lodges, a restaurant and bar, commercial resort accommodation and various tow knick-knacks to ferry skiers to the top of their runs.

Guthega serves as a winter base for downhill skiing, cross country skiers, snow-shoers and snow-boarders. The alpha adventurers head for Blue Lake to try out their ice climbing skills. But in summer, Guthega is pretty much dead. A ghost resort. Hopefully, this will change given the number of walkers I saw on the track.

It was now two hours past our lunch hour. A familiar pattern developing here, much to the chagrin of my fellow walkers. We found Garry’s vehicle, wheels still attached, piled in and headed for nearby Island Bend Campground on the Snowy River for a belated feed.

The campground was once the site of a construction village for the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

We ducked into a pleasant little nook with a picnic table and some soft grass for a post-prandial kip. All in all, a top day of alpine hiking with my walking companions, Joe, Chris, Neralie and Garry.

I had many more days of alpine adventures for my fellow Kosciuszkians. God bless their little walking boots. Maybe not so little.

Check out these Kosciuszko walks.

Snowies Alpine Walk: Perisher to Bullocks Flat.

Mt Jagungal: Kosciuszko National Park

Hiking the High Plains of Northern Kosciuszko

Exploring Long Plain: Landscape, History, and Wildlife in Kosciuszko National Park.

A Summer Hike from Kiandra to Mt Kosciuszko

Share this:

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

Mt Jagungal: Kosciuszko National Park

My walking companion, youngest son, had just swanned in from months of pounding the mountain trails of the Swiss Alps and Nepal. Lean and fit, he was keen for one final fling before returning to work in early November.

We tossed around the possibilities. Frenchman’s Cap, The Labyrinth, the Western Arthurs were his hot choices while Moreton Island or K’gari looked like cushy numbers for me.

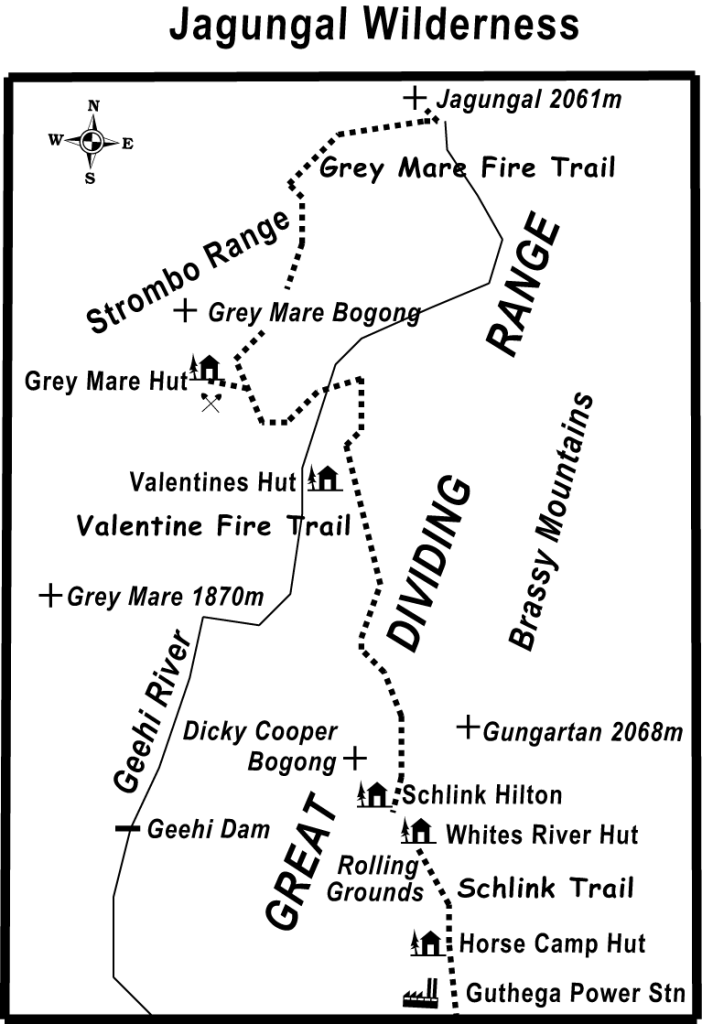

The art of compromise. An 80 kilometre outing to Mt Jagungal in northern Kosciuszko National Park. The iconic Jagungal Wilderness Area is part of The Australian Alps Bioregion, the only truly alpine environment in New South Wales as well as the only part of mainland Australia to have been affected by Pleistocene glaciation.

Jugungal Wilderness: The Weather Report.

Our timing was impeccable. The Bureau of Meteorology’s Snowy Mountains Regional Forecast promised us: Wednesday: ‘snow showers’ and ‘fresh to strong southerly winds’. The clincher was the ‘minimum of -2ºC, and a maximum of 0ºC’. More of the same for Thursday with relief coming on Friday: ‘fine sunny weather, minimum -3ºC, maximum 9ºC’.

We somehow misplaced Friday’s fine sunny bit. Youngest son, outfitted with cosy thermals and multiple fleece layers, seemed relaxed about all this snow stuff, so I wasn’t overly concerned. But I wondered if my warm Queensland blood was up to the task.

The Provedore

Once in Canberra I was despatched to Manuka to source the all important hiking rations. Too easy: a big bag of beer nuts, no-brand cups of soup, two-serve pastas, mountain bread, ten yoghurt coated muesli bars, tang, eight Laughing Cow soft cheese wedges, twelve mini Mars bars and two knobs of pepperoni salami to placate youngest son’s carnivorous tendencies.

But, when it was too late, at the isolated Whites River Hut, he discovered that his confidence in the largesse of this provedore was sadly misplaced. There is an old saying about living on the smell of an oily rag that seems apposite. But I will return to this well chewed bone of contention later.

More Information

Map: Geehi Dam: 1:25000.

Map: Jagungal: 1:25000.

Map: Tim Lamble: Mt Jagungal and the Brassy Mountains: 1:31680.

Map: Wyborn, D., Owen, M., Wyborn, L: Geology of Kosciuszko National Park: 1;250000. ( BMR Canberra 1990 ).

Hueneke, K: Huts of the High Country (ANU Press 1982).

Johnson, D, The Geology of Australia ( Cambridge University Press 2009 ).

Flood, J : Moth Hunters of the ACT: ( 1984 ).

Kosciuszko Huts Association: https://khuts.org

Photo Gallery: Jagungal Wilderness

Tuesday: Guthega Power Station to Whites River Hut: 10 kms.

With a 5.00 pm departure we left the bluebell coloured Camry orphaned at the Guthega Power Station, the Australian Alpine Walking Track entrance. The track zig- zagged steeply uphill.

With fine cool weather and a window of three hours to cover the ten kilometres to White’s River, there was no particular hurry and apart from a 240 metre altitude gain it was a most agreeable evening’s ramble, as we beetled along in a companionable silence.

Australia’s Sub-alpine Landscapes

We followed the winding track across a typical sub-alpine landscape of snow gum woodland interspersed with open grasslands. The sub-alpine zone in Australia is that in which snow gums are the only tree species, lying between approximately 1400 m and 1700 m. Above 1700 m to about 2000 m, on the Australian mainland, is the treeless alpine zone.

Vistas of extensive treeless grasslands unfolded along the valley floor. These grasslands are said to be the result of cold air pooling in valleys forming frost hollows, producing a microclimate inimical to the survival of trees and shrubs, even snow gums.

In the dampest parts where the water table is close to the surface, spongy bogs and fens dominate. The higher ridges are covered in snow gum woodland, the lower edge of the community terminating sharply, forming a definite tree line on a contour around each plain.

It was sobering to find huge swathes of the snow gum woodland burnt out, their dead branches arching over our heads. Lines of fire-ravaged hills retreated to the far horizon, but, on an optimistic note, the dominant snow gums were now suckering vigorously from their lignotubers.

In 2003 massive fires burnt much of the park and sections of the plateau were still closed until mid 2006. Fire is, of course, part of the natural regime of Kosciuszko, with an average of 100 days annually of high to extreme fire danger.

It has the dubious distinction of being one of the most fire prone areas in the world. Fortunately, this area from Guthega to Jagungal was untouched by the massive fires of the summer of 2019-2020.

We reached White’s on dusk. I wussed out, keen for a comfy bunk in the hut. Surprisingly, I met little resistance … for a change. The plummeting temperature, barely holding at 3ºC, dampened our enthusiasm for things outdoorsy: like sleeping in freezing tents, no camp fire, and fourteen hours incarcerated in a hike tent.

Whites River Hut

White’s River Hut, typical of many high country huts, was built in 1935 by sheep farmers who engaged in the transhumance of their flocks, grazing them on the high alpine meadows of the Rolling Grounds in summer, retreating to the protected Snowy River stations for winter. Summer grazing on high pastures ceased in the 1970’s.

Constructed of sheet iron, White’s is a basic, dingy hut, appreciated in cold, wet weather, but rarely used on hot summer days. Like most Kosciuszko huts it has sleeping bunks, a fireplace or woodstove, wood store, tatty table and bench seats and an outdoor dunny.

Whites is unusual in that it once had an additional, stand-alone four person bunkhouse known as ‘The Kelvinator’, for obvious reasons. If it is not obvious to the reader then Kelvinators were a famous brand of Australian refrigerators. This was the last refuge for desperate winter skiers, no doubt thankful to escape from the malevolent Rolling Grounds but usually arriving frozen to the core only to discover there was no room left in the main inn.

The main hut is also the refuge of the notorious Bubbles and Bubbles Jnr, bush rats extraordinaire: legends of High Country Huts as walkers and skiers record their exploits of marsupial derring-do and innate native rat cunning at avoiding all manner of water traps and flying footwear.

On a visit in 2005, Bubbles made off with our leader’s head torch, dragging it towards his bolt hole stopping occasionally to dine on its hard plastic coating. Tonight, these pint sized bush banditos were content with keeping son in a state of high alert as they tip-ratted through hut rubbish and skittered along the wooden beam highways above our beds.

For my part I slept as well as can be expected for a Queenslander. Cold air seeped through my down sleeping bag, thermal liner bag, two thermal shirts, a polar plus jacket, beanie, gloves, woollen socks x 2, thermal long johns and over trousers. How cold could it get?

Wednesday: Whites River Hut, Schlink Hilton Hut, Valentines Hut and Grey Mare Hut: 19 kms.

We found out in the morning. All was quiet. No birds, no Bubbles, no sound of running water. Just the muffled fall of light snowflakes susurrating against the hut. Nature called and I emerged at six o’clock and applied my final layer, a thick Gore-Tex rain jacket, which seemed to do the trick. Youngest son surfaced soon after, although I have observed that he normally lies doggo until Jeeves has a fire blazing and breakfast is on the way.

There is nothing like walking in a light snowfall. Cold it may be. But to be out walking on a high country trail in crisp alpine air, is an experience to be remembered. Our bodies quickly warmed up as we ascended towards Schlink Pass at 1800 metres.

In any case our warm gear and wind proofs kept us snug and dry. All too soon we topped the pass and descended to The Schlink Hilton. This twenty bunk ex-SMA hut was named after Herbert ‘Bertie’ Schlink, who was one of a party of four who were the first to complete the Kiandra to Charlotte Pass trip in three days in July 1927.

We ducked in, out of the drifting snowflakes, deposited plops of melting snow, removed several thermal layers, and then squelched off again to the start of the Valentine Fire Trail.

Valentine’s marks the start of The Jagungal Wilderness Area. Centred on Mt Jagungal (2060m), this isolated area is a bushwalking paradise: mountain peaks, snowgrass plains, high alpine passes, the massive Bogong Swamp and a derelict gold mine.

The area is closed to vehicles but numerous fire trails provide sheltered walking when bad weather closes in over The Kerries and Gungartan.

Valentines Hut

By 10.30, the snow showers clearing, we sighted Valentine’s Hut, its fire truck red livery standing out against a grey skeletal forest of dead snow gums. Valentine’s is my all time favourite high country hut. Another ex-SMA hut, this natty little four person weatherboard hut has a clean airy feel, with table, bench seats and a wood stove in its kitchen. A home away from home.

Other huts are usually dark, sooty, plastered with candle grease and graffiti and generally described as dirty and dingy. Valentine’s has been painted inside and out, has ample windows and, for added creature comfort, a newish corrugated iron dunny close by.

Youngest son, ever hungry, was keen for an early lunch in the snug comfort of Valentine’s, out of the clutches of the blustering southerlies. Two mountain bread roll-ups filled with peanut paste, salami and cheese, a mini Mars and a few handfuls of beer nuts vanished in a flash. He: “What’s next?” Well nothing.

Some grumbling about catering arrangements and we were on our way to the Grey Mare, but not before I deemed it politic to requisition a packet of cous cous from the ‘please help yourself food pile’. No self respecting bushwalker eats cous cous, not even the desperate.

The final leg would take us across Valentine’s Creek, over the mighty Geehi River (boots off for me), then up and over a 1700 metre alpine moor to Back Flat Creek with a final unwelcome crawl 60 metres up to the Grey Mare Hut for an early mark.

Grey Mare Hut

Grey Mare was a miner’s hut. Gold was discovered in the vicinity in 1894 at the Bogong Lead, later called Grey Mare Reef. Initially it was worked as a pit but flooding of shafts ended the first sequence of occupance in 1903. An output of 28.3 kgs of gold in 1902 made it one of the highest yielding gold fields in New South Wales.

A second phase of mining started in 1934 with an adit blasted to get to the reef. The ruins of a hut on the creek flats below dates from this period. A final attempt to get at the gold came in 1949 when the present hut was built.

The bush around the hut is littered with all kinds of mining knick-knacks: a crusher, a steam engine, a huge flywheel weighing more than two tonnes and a shambolic tin dunny teetering over the abyss of an old mine shaft ( since replaced with something safer).

The six berth hut is standard dingy but large and comfortable with a huge fireplace and the best hut views in the park. From our doorstep we had views northwards up the grassy valley of Straight Creek and peeking above Strumbo Hill, the crouching lion, Mt Jagungal, tomorrow’s destination.

Looking to the east I could see Tarn Bluff, Mailbox Hill and the Cup and Saucer which I visited in 2017. Behind us was the Grey Mare Bogong topping out at 1870 metres.

By three o’clock, the worms were biting and son was already scruffling through our rations looking hopefully for cups of soup and pasta with Nescafe caramel lattes and chocolate chasers to appease his now constantly rumbling tum.

Meanwhile, I set to with bush saw to lay in our wood supply for what was shaping up to be a windy, cold night. No problems with collecting bush timber here, the hut is set in a stand of dead snow gums. By five o’clock it was cold enough to rev up the fire.

Come dark we banked the fire and drifted to our bunks, snuggling down into warm bags. The predicted ‘windy’ conditions made for a restless night with a banging door and overhanging branches raking the corrugated iron chimney.

Thursday: Grey Mare to Jagungal and return: 22 kms.

Up at six o’clock in anticipation of the long walk to Jagungal and back. Snow showers again, a gusting tail wind catching our rucksacks and driving us sidewards off the Grey Mare Trail as we headed north. With Phar Lap out in front and old Dobbin coming at a steady gallop behind, we burned up the kilometres, hayburners from hell, past Smith’s Lookout (1748m), across the Bogong Swamp (dry), rock hopped over the Tooma River, and thence to our Jagungal access at the Tumut River campsite.

And not a single grey mare in sight. A heap of beer nuts and a yoghurt bar each and we were off again, an easy 220 metres climb onto the mist shrouded south west ridge, a sharp turn left and an even easier 160 metre ridge walk to Jagungal Summit at 2061 metres. The Roof of Australia, or near enough. The mist cleared…. how lucky was that?

Mt Jagungal 2061 m.

Jagungal is instantly recognisable from over much of Kosciuszko. A reassuring landmark for bushwalkers and skiers alike, a beacon… an isolated black rocky peak standing above the surrounding alpine plains. It is at the headwaters of several major rivers: the Tumut, the Tooma and the Geehi.

It was known to cattlemen as The Big Bogong or Jagunal. The later spelling, Jagungal, is considered by the old timers a latter day perversion. Jagungal appears on Strzelecki’s map as Mt Coruncal, which he describes as “crowning the spur which separates the Murray and Murrumbidgee Rivers”.

The aborigines often called mountains in the alpine zone ‘bogong’, indicating a food source, the Bogong moth. Europeans applied their own nomenclature to differentiate the Bogongs: Paddy Rushs Bogong, Dicky Cooper Bogong and Grey Mare Bogong.

Unlike most of the other Bogongs whose granitic origins are revealed by their characteristic whaleback profiles, Jagungal’s summit is distinctively peaky. It sports a lizard like frill of vertical rock towers, some intact, other lying in jumbled heaps.

Jagungal is different because it is capped by amphibolite, a black igneous rock more dense than granite, formed by the metamorphosis of basalts, the Jagungal Volcanics. Its origins date back to 470 to 458 mya, to the Middle Ordovician. It is surrounded by the Kiandra Volcanic Field, part of a belt of volcanoes called the Molong Volcanic Arc.

During the The Ordovician ( 485 to 444 mya), Australia was part of a single super-continent and much of Eastern Australia was covered by the sea. Chains of active volcanoes occupied parts of central New South Wales. These were mainly submarine volcanoes but some emerged to form small islands with fringing limestone reefs. The Ordovician saw the first appearance of corals and land plants.

Jagungal was ascended by Europeans in the winter of 1898 when a party from the Grey Mare Mine climbed it using primitive skis called ‘Kiandra snowshoes’.

Ours was a much less adventurous walk, but we still savoured our time on the summit. Especially magnificent were the views south to the snow capped Main Range, four days away. It was so clear that we could even discern Victoria’s Mt Bogong on the far southern horizon.

But the cold wind soon drove us into a protected sunny nook just under the summit. We hunkered down, lunched, son eased into one of his regular catnaps…. no doubt dreaming of Nepal and wolfing down a huge bowl of Nepali boiled potatoes and rice; or perhaps a large slice of pizza; or even, given our now parlous food situation, a plate of succulent fried Bogong Moths.

Bogong Moths

I had noticed on a previous trip and again on our ascent today, huge raucous flocks of crows cawing around the steep summit cliffs. I had seen the same phenomenon on Mt Alice Rawson near Kosciuszko. Inexplicable at the time.

Recently, I came across an explanation. The ‘crows’, actually Little Ravens (Corvus mellori), were gathering to feed on Agrotis infusa, the drab little Bogong moth, found only in Australia and New Zealand. To escape the summer heat, these moths migrate altitudinally and set up summer holiday camps in the coolest places in Australia, the rock crevices of the alpine summits.

They come in millions from western New South Wales and Southern Queensland, distances in excess of 1500 kilometres, often winging in on high altitude jet streams, and settle in crevices and caves, stacked in multiple layers, 17,000 of them in a square metre, where they undergo aestivation or summer hibernation.

The migrations seem to be a mechanism to escape the heat of the inland plains and they gather in the coolest and darkest crevices on western, windward rock faces. A tasty morsel for our corvid buddies.

Aborigines and the Bogong Moths

With the ravens came the aborigines, from Yass and Braidwood, from Eden on the coast and from Omeo and Mitta Mitta in Victoria. All intent on having a good feed and a good time. Large camps formed with as many as 500 aborigines gathering for initiation, corroborees, marriage arrangements and the exchange of goods.

It is thought that advance parties would climb up to the tops, and if the moths had arrived they would send up a smoke signal to the camps below. The arrival of the moths is not a foregone conclusion. Migration numbers vary from year to year.

Some years they are blown off course and out into the Tasman Sea. 1987 was a vintage year, but in 1988 the bright lights of New Parliament House in Australia’s bush capital, acted as a moth magnet, and they camped in Canberra for their summer recess, unlike our political masters.

Men caught the moths in bark nets or smoked them out of their crevices. They were generally cooked in hot ashes but it is thought that women sometimes pounded them into a paste to bake as a cake. Those keen enough to taste the Bogong moth mention a nutty taste.

Scientists say they are very rich in fat and protein; this diet sustained aborigines for months and the smoke from their fires was so thick that surveyors complained that they were unable to take bearings because the main peaks were always shrouded in smoke.

Europeans often commented on how sleek and well fed the aborigines looked after their moth diet. Edward Eyre who explored the Monaro in the 1830’s wrote: “The Blacks never looked so fat or shiny as they do during the Bougan season, and even their dogs get into condition then.” At summer’s end, with the arrival of the southerlies, the moths, aborigines and ravens all decamped and headed for the warmer lowlands. As did my travelling companion and I.

Friday: Grey Mare Hut to Horse Camp Hut: 24 kms

Of necessity, a long day’s walk ahead to put us close to our Guthega exit. Windy and cool again, and no sign of the fine sunny weather promised by our BOM friends. Which was just as well as my radiator was boiling on our way up the steep 200 metre climb out of Back Creek en route to Valentine’s.

Today we would be walking south, towards the Main Range. Here was an excellent opportunity to identify from our map the classics of Kosciuszko walking that had been shrouded in mist on our outward walk: The Kerries, Gungartan, Dicky Cooper Bogong, the Rolling Grounds, Mt Tate, Mt Twynam and the biggest Bogong of all, Targan-gil or Mt Kosciuszko.

Horse Camp Hut

Late in the afternoon we turned off the Schlink and found our way to Horse Camp Hut, tucked in snow gum woodland 300 metres below the Rolling Grounds, a high altitude granite plateau above the tree line at 1900+ metres, cold, windy and exposed but spectacular. It is said to be very difficult to navigate in bad weather.

I noted in the hut log book that a number of winter skiers had ‘GPSed’ their way to Horse Camp from the Rolling Grounds. It is claimed that the Rolling Grounds are so named because during the summer grazing, stock horses would enjoy a good old dust bath and roll in the many depressions that dot this high altitude plateau.

Horse Camp Hut, of Lilliputian dimensions, still manages a serviceable fireplace, kitchen cum lounge cum wood storage, table, a few decrepit chairs and a separate room with a wood stove and two bunks.

Apparently nine girls from SGGS Redlands and their gear were crammed into the room on a wild wet night years ago. With temperatures hovering at 2ºC I lit the fire and we polished off whatever meagre rations were left: soup, pasta, noodles and Nescafe Latte laced with some suspect Milo lifted from the hut ‘left overs’.

Saturday: Horse Hut Camp to Guthega Power Station. 4 kms.

Up at 6.00. Freezing and no fire or breakfast genie this morning. We set out ASAP, fully rugged up, as the sun lifted over Disappointment Ridge for our final four kilometres into Guthega, downhill. Hopefully Bluebell would be still where we left her. She was, and despite her coat of frost, she fired up and we were away. Off to Sawpit Creek for breakfast, a coffee in Cooma then a slap-up feed and a cold goldie back in Canberra. A fitting end to an outstanding alpine jaunt.

Other Kossie Trips.

Share this:

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

A Hike to Bluff Tarn and The Brassy Mountains in Kosciuszko National Park

Exploring Australia’s High Country.

by Glenn Burns

Nestled high up in Kosciuszko National Park’s Jagungal Wilderness Area at about 1850 metres is Bluff Tarn. It is a small alpine lake set in an extensive landscape of alpine ridges, swiftly flowing rivers and the vast swamps that make up the area loosely called Australia’s High Country. Robert Green in his book ‘Exploring the Jagungal Wilderness’ describes Bluff Tarn as “…one of the prettiest spots in the mountains”.

On an early November afternoon I set off with five bushwalking friends, Sam, David, Joe, Richard and Brian on a seven day, 60 kilometre cross country circuit from Guthega to Bluff Tarn on the upper Geehi, then to Tin Hut on the headwaters of the Finn River.

Our route started at Guthega Power Station and took in Whites River Hut, Gungartan (2068 m), The Kerries Ridge (2000 + m), Mawsons Hut, the Cup and Saucer (1934 m), Bluff Tarn, the Mailbox (1900 + m), the Brassy Mountains (1972 m), Tin Hut, the Porcupine (1960 m), and Horse Camp Hut via the Aqueduct Track.

THE WEATHER

The alpine forecast wasn’t quite what this leader was hoping for. Showers most days, starting with a possible thunderstorm for our first day on the track. Temperatures would be pretty friendly though: 7°C to 18° C . Apparently, our luck really would desert us on Friday, 6 days hence. A 90 % chance of 20 to 40 millimetres.

Upgraded later in the week to 100 millimetres. I was disinclined to hang around to test out that old saying that ” there is no such thing as bad weather, only unsuitable clothing”.

November is my preferred alpine hiking month. The weather is starting to settle; night temperatures are bearable, day temperatures are just perfect; and even light snowfall makes for magical walking. Water is abundant and easy to find.

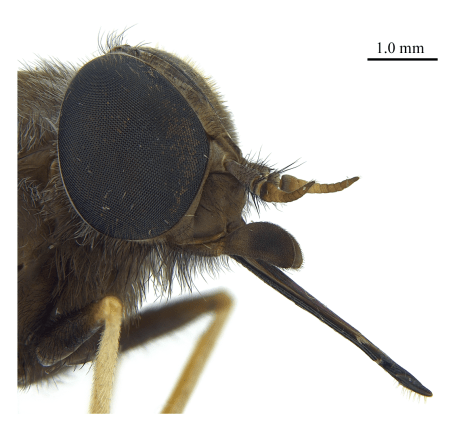

Wildflowers are blooming but best of all, those nuisance bush flies and their high country cousins, the biting Horse/ March/ Vampire flies have yet to descend on the unsuspecting walker.

Horse or March flies appear as adults almost unvarying in the second week of December and hang around all the way through to February. Although they are called March flies they are rare in alpine areas in March.

These are large members of the Family TABANIDAE (genus Scaptia). March flies, at 25 mm, are the largest of our biting dipterans. The female does the blood sucking bit, while the benign male is content to feed on nectar and pollen.

On one mid-December Kiandra to Kosciuszko trip in 2006 with my friend Brian, March fly numbers were truly appalling. There was no escape from these pests. They operated on a sunrise to sunset roster and were so bad that it was unpleasant to stop for the vitals like meal breaks, water stops and even navigation checks.

They attacked with persistence and determination, and could bite through clothing with impunity. We often tried to find huts for meal breaks, but failing that, donned fly veils, rain jackets and long trousers or rain pants to keep the blighters at bay while we ate.

As Queenslanders, our preferred hiking apparel is usually shorts and short sleeved shirts, not thick rain jackets and long trousers. On the warmish December days the rain jacket/rain pants garb was not for the faint- hearted.

Alpine Wildflowers: Photos by Sam

More Information

Map: Geehi Dam: 1:25000.

Map: Jagungal: 1:25000.

Map: Tim Lamble: Mt Jagungal and The Brassy Mountains: 1:31680.

Green, K and Osborne, W: Field Guide to Wildlife of Australian Snow-Country. (New Holland 2012).

Hueneke, K : Huts of the High Country (ANU Press 1982).

Codd, P , Payne, B, Woolcock, C : The Plant Life of Kosciuszko. (Kangaroo Press 1998).

McCann, I: The Alps in Flower. (Victorian National Parks Assn 2001).

Slattery, D : Australian Alps. (CSIRO 2015).

Kosciuszko Huts Association: Website

Map of Bluff Tarn: Jagungal Wilderness : Kosciuszko National Park.

Sunday: Guthega Power Station to Whites River Hut: 8 kms.

With cars stabled at the Guthega Power Station we wandered off, ever upward. Sam, David and Richard setting a pretty lively pace under a low leaden sky. There were just enough irritating spots of rain to encourage the old laggards creaking along in the rear to lift our pace.

Mid-climb, a squadron of two-wheeling weekend warriors swooped around a blind corner. Braking furiously, some nifty controlled slides, a spray of gravel, and they were off again, pedalling downhill at speed. Eat my dust, Boomer.

Our mountain biking friends also anxious to reach cover before the heavens opened. Given my weighty rucksack, I too, could be sucked into this mountain biking game. Though I’m pretty sure that I would end up pushing said mountain bike up the current 250 metre ascent.

I may curse my heavy rucksack but mostly I am grateful for the good things its contents make possible: a snug downy sleeping bag, the protective cover of my little Macpac one-man tent, a comfy sleeping mat and a generous supply of crystallised ginger and chocolate licorice bullets.

By 3.30 pm we landed at Whites River Hut, disconcerted to find four tents moored on the creek flats below the hut. The tents belonged to a bunch of hikers from the Newcastle Ramblers Bushwalking Club, apparently intent on doing much the same circuit as we had planned.

No sweat. Plan B. They were no shirkers, these Novocastrian types. Instead of lolling around the hut for the afternoon (as I would have happily done), they struck out on a somewhat damp stroll across the tops from the Rolling Grounds to nearby Dicky Cooper Bogong (SMA 0113: 2003 m). The place name ‘Dicky Cooper Bogong’ recognises the the traditional Aboriginal custodian of this mountain, one Dicky Cooper.

Aborigines inhabited these highlands as far back as 21,000 years ago with evidence of their occupation coming from Birrigal Rock Shelter in Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve and many sites in the upper Snowy River. Small stone scatters can be found in the alpine landscapes with the highest being a collection found near the saddle of Perisher Gap (1800m).

It is well known that aborigines travelled to these highlands in the summer months to collect and eat the abundant Bogong Moths which were found sheltering in the rocky crevices of all the major outcrops in the Snowy Mountains. I have written extensively about this in my trip report Kiandra to Kosciuszko.

Many place names in the Alps have been derived from local Aboriginal languages: Jagungal, Jindabyne, Talbingo, Yarrangobilly, Suggan Buggan, Mitta Mitta and Tumut. It is not hard to find many other examples from your maps. Apparently the Geographical Place Names Board of NSW was considering giving Mt Kosciuszko a traditional Aboriginal name (Kunama) which would sit alongside its current name. But it hasn’t happened.

On dusk the predicted showers finally arrived, as did a damp and dishevelled clutch of boys and their teachers from Bathurst. No hanging out in comfortable huts for this lot: they pitched their tents in the rain, had a quick feed then quietly settled down for the night.

Meanwhile back at the ranch, Brian’s traditional first night treat of bangers and mash seemed to have spread like some medieval contagion. Most of my fellow hikers had succumbed to this dubious culinary delight and were enthusiastically whipping up dollops of instant mash leavened with green peas, sun-dried tomatoes, and heating neatly folded alfoil cylinders containing pre-fried bangers: beef for preference but maybe lamb & rosemary for those with more delicate taste buds.

Monday: Whites River to Mawsons Hut via Gungarten and The Kerries: 11.5 kms.

Showers overnight but with the mist lifting from The Rolling Grounds and Gungartan, things were on the up and up, weather wise. As were Brian and Joe, clanking about in the dark, soon after 5.30 am. Disturbing my slumber.

Our crafty Newcastle Bushwalkers friends still got the jump on us and had drifted off by 7.30 am. A comprehensive report of their walk can be found in the Kosciuszko Huts Association Newsletter: No 178 Autumn 2018. But we were soon hot on their heels desperate not to be pegged as a bunch of idle slackers.

Today’s walk would take us to Schlink Pass thence to Gungartan, down into Gungartan Pass, up along The Kerries to Mawsons Hut, tucked in a thicket of snow gums at the northern end of The Kerries. But first, the 300 metre climb from Schlink Pass to the Main Divide through snowgum forest.

The Kerries Ridge (2000 m), a spur of the Great Dividing Range, offers open alpine walking at its very best… in fine weather. This trackless ridge is a landscape of huge granite outcrops and vast alpine meadows. Suffice to say by the time we were well into The Kerries traverse, we watched a succession of storm cells sliding along the high peaks to our north and west, heading our way.

Come lunchtime we hunkered down in the lee of a granite boulder, sheltering from the rain that Hughie dropped over us . I’m always a bit disconcerted to be caught out in the open alpine zone with distant lightning and thunder rolling around.

But my fellow travellers didn’t seem all that concerned as they disappeared into their rain jackets and munched contentedly on muesli bars, dry biscuits and slabs of cheese. The rain eased to light drizzle, and we moved out, heading north, following the crest.

A further four kilometres of alpine tramping dropped us down to Mawsons Hut. Joe and Richard navigated us off the heights and down to our destination. Pretty much spot on. Being tucked into a grove of snowgums, the hut can be a tad difficult to find. Mawsons was deserted. A Novocastrian-free zone. When we last saw them ambling across Gungartan Pass, they were heading for Tin Hut on the Finn River. Another afternoon thunderstorm and hail swept through, driving us into the hut to finish drying our gear and have a feed. No fry up tonight. It was strictly dry rations for the rest of the week for this lot.

Tuesday: Day Walk to Cup and Saucer, Bluff Tarn and The Mailbox: 7 kms.

Fine weather and an easy day walk called us to the hills on our third day. From Mawsons we would cross the Valentine River; scamper up the Cup and Saucer; cut across the grasslands of the upper Geehi to Bluff Tarn; returning to Mawsons via The Mailbox. That was the plan and for once I stuck to it.

We left Mawsons in brilliant weather. A superb day of walking beckoned. We dropped down to the Valentine which still flowing strongly from the spring thaw but we sussed out a partly exposed gravel bed. Richard, Brian and Joe volunteered to check it out. Sacrificial lambs. I am told that there is nothing so grumpy as a leader with wet boots this early in the day.

The Cup is a granitic dome ( Happy Jacks Monzogranite: < 20 % quartz) sitting on its saucer, a shelf of nearly horizontal granitic rock. This Silurian granite is 444 to 419 my old and dates from a time when the Earth entered a long warm phase which continued for another 130 million years.

Oceanic life flourished and vascular plants increased in size and complexity. The supercontinent Gondwana drifted south and extended from the Equator to the South Pole. Australia was located in the Equatorial zone.

From a distance the Cup and Saucer are well named and form an unmistakable landmark for kilometres in all directions. Topping the Cup is an old Snowy Mountains Authority Trig 133 standing at 1904 metres. This was our first objective. From the top of the Cup we should be able to see a line of travel across to Bluff Tarn.

It was only one and a half kilometres to the Cup but swampy ground made our approach more circuitous than I anticipated. My original plan was to clamber up the long south western ridge to reach the Trig. But the final steep and damp and moss encrusted granite slabs thwarted all but Brian. Unsurprising really. His friends call him “Straight Line Brian”.

Contouring or backing off isn’t part of Brian’s bushwalking lexicon. But the rest of us were content to retreat and scarpered up the more accessible northern face … without any further difficulties. Where upon we settled on the rock outcrops to take in the landscape and enjoy a leisurely morning tea.

From the summit of the Cup and Saucer unfolded a vast alpine panorama. To the east rose up the high range of the The Brassy Mountains, part of Australia’s Great Dividing Range system. To our east was the valley of the Geehi River and its tributary, the Valentine River.

Directly to our east and just below our vantage point is the Big Bend. Here the Valentine swings off its northerly course to flow south-west another six kilometres to its junction with the Geehi. No doubt the granitic dome of the Cup and Saucer forms a structural control over the direction of flow of the Valentine.

To our north , less than a kilometre across the swampy headwaters of the upper Geehi valley was Tarn Bluff (1900 m) with Bluff Tarn tucked somewhere still out of sight.

Bluff Tarn

Bluff Tarn certainly met our all our expectations. It is, indeed, “one of the prettiest spots in the mountains”. But is is not, strictly speaking, a tarn. Merely a lake. My inner pedant would tell you that a tarn is “a small mountain – rimmed lake, specifically one on the floor of a cirque”. No cirque here. But quibbles over geographical precision couldn’t detract from the beauty of our surroundings.

While Bluff Tarn is a small lake, it is fed by a major headwater tributary of the Geehi, with the stream cascading through and over large rounded boulders. The lower reaches of the cascades were still covered by a thick snowbank, even though we were only a few days short of the start of summer.

I’m not sure of the origins of Bluff Tarn, but it appears to be formed as a shallow pool fed by the cascades dropping over a shelf of harder rock. Its outlet was restricted by a prominent bank of coarse, unsorted gravels. It would have been interesting to spend more time checking out Bluff Tarn but the worms were biting and my fellow walkers had lost interest in playing in the snow and my geological musings. They were itching to move on for their lunch break.

Our lunch spot was Mailbox Hill about a kilometre due east of Bluff Tarn … first though, one of Brian infamous uphill flat bits to raise a sweat and develop a healthy appetite for lunch. The Mailbox or Mailbox Hill, your choice, is a series of rounded outcrops standing at about 1910 metres. It was named The Mailbox because, I guess, mail was collected there by the cattlemen in the days of summer grazing.

The Kosciuszko Huts Association, my alpine bible, have researched the origin of the placename: Post was delivered to the men on the lease by a Mrs Bolton. She was engaged to deliver the mail on horseback to the Grey Mare Mine, travelling the old dray route from Snowy Plain across to Strumbo Hill. Ernie Bale recalled that on Mailbox Hill “there was a clump of rocks and they had shelves in them and she used to leave the mail for Mawsons Hut – it was always known as the Post Office – she used to leave the mail and put a rock on top of it“.

After a leisurely lunch spent sprawled on slabs of rock well out of the reach of those pestilent little black alpine ants, we wandered off towards Mawsons keeping a weather eye on the clouds building over The Kerries. But not before some male argy bargy about its location.

Later in the afternoon our Newcastle friends arrived from Tin Hut while the males were down at the creek having sponge-downs. We spent a very congenial evening around the campfire trading tall tales, listening to their hiking stories from far flung parts of the globe and getting some very handy gear tips from Shayne.

Wednesday: Mawsons Hut to Tin Hut: 8.5 kms.

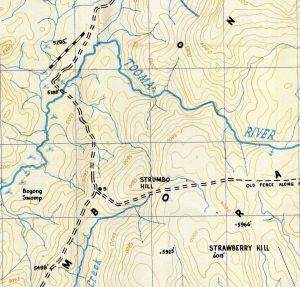

A pleasantly cool and clear high country morning. By 8.00 am we were packed and on the road. Our route would take us across to the western bank of the Valentine then a gentle 80 metre climb following an old fence line that is marked on my old Tim Lamble map.

Tim’s maps, if you can get hold of one, provide a plethora of details useful to the bushwalker and skier: rock cairns, old fence lines, posts, old yards and even magnetic bearings. Anyone interested in maps will appreciate the quality of Tim’s cartography.

We followed the fence line up to a low rocky knoll overlooking the north-south trending Brassy Mountains (1900m), directly in front of us. Klaus Hueneke in his well researched Huts of the High Country (ANU Press 1982) gives an explanation of the naming of Brassy Mountains .. “named in the early days on account of the reflection from running water over rocks. At certain times this resembles polished brass and can be seen from up to 16 kms away.”

A navigation huddle soon sorted out our next moves. The Brassy Peak (1900 m) was directly in front of us while The Big Brassy (SMA Trig 1972 m) was off to our south east, directly behind The Brassy Peak. But between our eyrie and The Brassy Mountains were the swampy headwaters of Valentine River.

I had originally planned to follow the main divide of the Brassy Mountains south to Tin Hut. But an easier option was simply to cross the swamp and then contour along the western base of the Brassies keeping the thick heath just to our left but staying above the fens and bogs of the Upper Valentine to our right ... sound strategy in theory.

But before we trundled off towards Tin Hut there was plenty of time to clamber up to the rock cairn sitting atop The Brassy Peak. From here we looked westward over the vast network of fens and bogs of the upper Valentine to the craggy outline of the Kerries Ridge which we had traversed three days ago.

Bogs and Fens

The upper Valentine is a wide alpine valley of impeded drainage: a fluvial landscape of bogs and fens. A fen is a specific geomorphic and botanical entity: namely still clear, pools of standing water with ground-hugging matted plants and the easily recognisable Tufted Sedge, Carex gaudichaudiana. A number of small but showy flowering plants manage to thrive in these waterlogged conditions: the pale purple Mud Pratia (Pratia surrepens), the pale cream or white Dwarf Buttercup (Ranunculus millanii) and the white Rayless Starwort (Stellania multiflora).

Bogs are areas of wet, spongy ground also found in areas of impeded drainage. Floristically bogs are dominated by Spagnum Moss (Spagnum cristatum) and associated with a variety of rushes and sedges, especially the Tufted Sedge. Bogs are associated with the decomposition of organic matter which will ultimately form peat.

These high alpine valleys are commonly underlain by peats formed by the decomposition of plant material after the last glacial period (15000 years ago). The peats are important for absorbing and regulating waterflows in alpine Australia, thus are listed as protected communities under both State and Federal legislation. (PS: tell that to the brumbies).

So with sodden boots and a sense of achievement we pulled into Tin Hut after a full morning’s hiking; just in time for another well deserved bite to eat. Always looking for the next feed. Tin has a bit of reputation for being difficult to locate in bad weather and is hidden in a belt of snowgums. But with fine , clear skies this was no issue for us.

Tin Hut

Tin is the oldest hut in the High Country built specifically for ski touring. Its origins go back to Dr Herbert Schlink’s attempt at the first winter crossing from Kiandra to Kosciuszko. Schlink needed a staging post for his final push along The Great Divide. In the summer of 1925/1926 a bespoke hut was built on the site of an old stockmans’ camp at the head of the Finn River. As 2017 was the 90th anniversary of its construction, our visit was timely.

It is called Tin Hut because the roof and walls are constructed of corrugated iron. Some of the timber and iron for its construction was packed in by horseback across The Snowy Plain and The Brassy Mountains. It had a wooden floor and was lined with tongue and groove with the door opening to the east. Initially it was stocked with a horse rug, 24 blankets, a stove, tools and firewood. When Schlink’s party arrived from the south, a blizzard trapped them in the hut for three days, forcing them to give up the 1926 attempt.

On 28 July 1927 Dr Schlink, Dr Eric Fisher, Dr John Laidley, Bill Gordon and Bill Hughes skied out of Kiandra to reach Farm Ridge Homestead on the first night. Excellent snow cover allowed them to reach Tin Hut by 1.00 pm on the second day. They pressed on to the Pound Creek Hut (now Illawong Hut) on the second night. They completed the first winter traverse finishing at Hotel Kosciusko on the third day.

In 1928 Tin Hut served as the base for two winter attempts to Mt Jagungal. The party led by Dr John Laidley skiing to the summit…. for just the second time in history.

In 2017 restoration work on Tin commenced with a partnership between the Parks Service and the Kosciuszko Huts Association. Men, gear and materials were helicoptered in for the major facelift. One KHA member, Pat Edmondson, eschewed the helicopter ride and walked in from and out to Schlink Pass. Pat was over 80 years old. I can only hope that I can still climb from Schlink Pass to Gungartan when I turn 80.

Afternoon stroll: Tin Hut to The Porcupine & Return: 5.5 kms.

Brian, ever keen on filling in his (and our) afternoons, decided that we shouldn’t waste time hanging around the hut. A more productive use of our time would be a quick jaunt over to The Porcupine, a nondescript alpine ridge (SMA 0109 :1960 m) which separates the Finn River from the Burrungubugge River.

From the hut we climbed the long ridge behind the hut to a knoll from which we could look across to the Trig on The Porcupine. Unfortunately, a very steep drop into a saddle then a climb back up to the Trig separated us from our quarry on this decidedly warmish afternoon.

Brian and his co-conspirators Richard and Joe were still keen as mustard, happy to descend and climb up again onto The Porcupine Ridge. David and Sam seeing the lie of the land, sensibly returned to Tin Hut for an afternoon of leisure. The walk to Porcupine is a scenic enough walk, but on reaching The Porcupine ridge I observed that the heat was getting to them and so the lads weren’t pushing me to go any further. Bless their little hot socks.

We waddled back, avoiding the dreaded climb back up the knoll and reached Tin about 4.00 pm and set about a major rehydration, downing multiple cups of tea, soups and choc-au-laits. An evening perched around the campfire finished off a very satisfying day.

Thursday: Tin Hut to Whites River Hut : 7.5 kms

The easiest route to Whites was to climb the long ridge which separates the Valentine and Finn Rivers, keeping Gungartan to our west. An ascent of a mere 200 metres vertical, but with dense knee-high heath and the odd snake or ten lurking underneath, it seemed endless.

One snake had decorously draped its ectothermic body across the top of a heath bush, obviously hoping to warm up in the feeble sunlight and frighten the bejesus out of a passing bushwalker.

Once on top of the Great Dividing Range we bypassed Gungartan, skirting around its rocky spine until we had a view of Guthega Village.

Time for a snack stop, perched atop huge boulders. A well tested strategy to keep out of the clutches of the maurading hordes of those little black alpine ants that swarm over any rucksack carelessly tossed on the ground. More disconcerting is their ability to overrun boots, climb up gaiters and finally ascend the thighs of any alpine rambler. Trying summer camping in Wilkinsons Valley and tell me how it goes.

Alpine Ants: Iridomyrmex sp.

The ants are probably Iridomyrmex sp, which my copy of Green and Osborne’s Field Guide to Wildlife of the Australian Snow-Country tells me are ‘ a conspicious part of the fauna in a few habitats, such as herbfield and grassland…. this omnivorous ant is the only common ant species in the alpine zone.’

It nests in waterlogged areas such as bogs, fens and wet heaths, and raise their nests above the water surface by constructing a mound of plant fragments in low vegetation. They are also found in tall alpine herbfield and dry heath.”

From our rocky eyrie we were treated to superb views across this small patch of Australia’s alpine wilderness. Time also for a weather update from duelling smartphones. Tomorrow: (Friday): 90 % chance of 20 to 40 mm. Maybe 100 mm. No arguments about pulling out a day early.

After a good laze around we skirted Gungartan and commenced the long descent to Schlink Pass (1800 m). Landing in the pass, a mutiny of the “are you stopping for lunch ? “ type broke out. Ever the considerate leader (probably not) , I caved in and we propped for lunch. Whites River Hut only one tantalising kilometre downhill.

We reached Whites River Hut soon after 2.00 pm. No interlopers on the radar so we had the place to ourselves. Despite tomorrow’s unfriendly weather report everything here was pretty relaxed. The usual suspects weren’t badgering for an afternoon walk (unusual), the weather was warm and sunny so a lazy afternoon beckoned.

We enjoyed a quick cat lick in the nearby icy snow-fed creek…. very quick, did any washing then spread clothes out to dry. The rest of the afternoon was filled with consuming cups of tea/coffee/soup; horse trading of leftover goodies, cutting wood, firing up the stove and reading whatever came to hand. Inside the hut were recycled Kosciuszko Hut Magazines and the hut log book.

Over the years the Whites River Hut log has provided us with many hours of very entertaining reading: the adventures of Bubbles the Bush Rat; the trolling of some trip leader called Robin and heaps of very well executed drawings and cartoons. Mr Klaus Hueneke should write a book about this stuff.

Friday: Whites River Hut to Guthega Power Station via Aqueduct Track and Horse Camp Hut: 10 kms.

I peeked out. Heavy roiling clouds were brewing over Gungartan and heading our way.

By 8.00 am we had beetled off along the Munyang Geehi road before swinging off onto the Aquaduct track which crosses the Munyang River via a weir. Nearby is an old SMA hut…locked to keep that mountain biking, skiing and bushwalking riff-raff out. Especially those dastardly mountain bikers.

The Aquaduct track is a gem of a walk. It winds above and parallel to the Munyang River, weaving around the hills on the 1800 metre contour. My kind of walking.

Mid morning we lobbed into the refurbished Horse Camp Hut for a final feed. I had been to Horse Camp before, returning from an early spring walk to Mt Jagungal with my youngest son. We got to Horse Camp just on dark. I remember how bitterly cold it was, how daggy the hut was and how our evening meal was pretty sparse, even by my standards.

Since then the Kosciuszko Huts Association and the Parks Service had been very busy and the hut was looking very spruce indeed. Unlike the young guy who had taken up residence in the hut. He was obviously there for the long haul or maybe the end of the world and had somehow dragged in all manner of heavy duty camping gear.

Horse Camp Hut

Horse Camp is a two room, iron clad hut set in a belt of snow gums under The Rolling Grounds. Its construction history is a bit fuzzy but was built initially in the 1930s as a shelter for stockmen working the snow lease owned by the Clarke brothers. It has the main elements of a traditional grazing era mountain hut with a bush pole frame, steeply pitched gabled roof, clad with short sheets of corrugated iron that could be packed in on horses.

At some stage over the decades it was partitioned into two rooms – a northern bunk room with a pot belly stove and the main kitchen room. A ceiling loft was added as well as a wooden floor and nifty three panel narrow windows. Several of the modifications were done by the Snowy Mountains Authority in the early 1950s. The SMA used Horse Camp as a base for their horseback survey teams working on the first Snowy Mountains Project, the Guthega Dam and associated infrastructure.

Leaving our young prepper friend to his preparations for the Covid 19 lockdown, we drifted off. A quick descent to the Guthega Power Station to find our vehicles waiting patiently in the car park, wheels and windscreen wipers still attached, and ready to transport us back to Canberra. But not before we detoured into the Parks Visitors Centre Parc cafe in Jindabyne for a selection of their satisfyingly greasy offerings, all washed down with a decent coffee.

As always, a big thank you to my band of merry bushwalking companions: Sam, David, Joe, Richard and Brian. May we enjoy many more rambles in the back blocks of Australia’s magnificent High Country.

More Hikes in Kosciuszko National Park.

Share this:

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Print (Opens in new window) Print

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

Kiandra to Canberra Hike on the AAWT. A Late Autumn Traverse.

by Glenn Burns

I dug out my old journal of our Kiandra to Canberra hike after the 2019/2020 summer fires damaged parts of the northern section of the Australian Alps Walking Track ( AAWT) . I have visited the Northern Plains many times and was fortunate to walk from Kiandra to Canberra several years ago with some friends just before the devastating fires. Here is my account of that trip.

Much of the landscape we hiked through then was relatively intact . However in the summer of 2019/2020 this all changed. The summer fires burnt out the New South Wales trail head at Kiandra including the old Kiandra Court House, Wolgal Lodge and Matthews Cottage.

The last three days of the AAWT traverses Namadgi National Park in the Australian Capital Territory. In this section the Orroral Valley and Mt Tennant were burnt. Amazingly, the old Orroral Homestead was saved.

Through the years since the early 1970s I have wandered many a kilometre over Australia’s High Country and more than once have I peered through the grimy window of a high country hut into the pre-dawn gloom… often sleet or rain or mist swirling around outside.

Excellent… back to the sack for another forty winks. But then I hear my fellow hikers. Pesky eager beavers all. Busy rustling around, pulling on boots, donning warm stuff and getting ready their rain/snow gear. Champing at the bit , ever keen to hit the trail.

Photo Gallery

And so it was for five walkers on a late autumn, an eight day traverse of the final northern section of Australian Alpine Walking Track (AAWT), stretching 105 kilometres from Kiandra on the Snowy Mountain Highway to Namadgi Park HQ on the outskirts of Canberra.

The complete 659.6 kilometre AAWT crosses some of Australia’s remotest and highest alpine mountains and snowgrass plains with a weather regime that can be very hot on occasions but is more often than not cold, wet and highly unpredictable.

As Alfred Wainwright, a famous English fell walker, wrote: ” There’s no such thing as bad weather, only unsuitable clothing.”

Useful Information

NSW Dept of Lands: 1: 25000 maps : Ravine, Tantangara, Rules Point, Peppercorn, Rendezous Creek, Corin Dam, Williamsdale.

NSW Rural Fire Service Brochure: Bushfire Safety for Bushwalkers.

Chapman, J Chapman, M & Siseman J: Australian Alps Walking Track (2009)

ACT Dept of Environment: 1:20000: Namadgi Guide & Map

Day One: Saturday 11 May: Outward Bound: Kiandra to Witzes Hut: 12 kms.

Just after midday, youngest son Alex taxied our hire van to a halt outside the old Kiandra Courthouse since destroyed in the 2019/2020 summer fire season. The Old Court House was the only remaining building of the old gold mining town of Kiandra: population in 1859, 10,000; now.. zero population.

A sudden population explosion as five walkers plunged out of the warm van and into a blast of cool air: Ross , Leanda , Peter, John and last but not least, their esteemed and worthy leader, yours truly.

The race was on for the few sunny spots out of the cool blustery wind. We wolfed down our Cooma take-aways, bade Alex a fond farewell, then hit the track, the Nungar Hill Trail.

Our afternoon on the AAWT took us northward over rolling snowgrass plains at about 1450 metres, broken only by occasional alpine streams, which we forded with dry boots and socks intact: the Eucumbene River, Chance Creek, Kiandra Creek and just before Witzes Hut, Tantangara Creek.

After Chance Creek we climbed to the crest of the Great Dividing Range, known locally as the Monaro Range. A minor blip on this undulating high plains landscape.

The seven day BOM forecast looked agreeably benign: early frosts (a mere -1° C) followed by sunny days (14° C). Perfect timing. But meteorology has a way of biting bushwalkers on the bum. In May this year maximum temperatures averaged 8.2°C while minimums hovered around a miserable 2.8°C. With a record low of minus 20°C, Kiandra is one of the coldest places on the Australian mainland.

Fortunately for this leader, my walking companions, all experienced bushwalkers, were kitted out for all eventualities. But most impressive of all was that they remained unfailingly positive and obliging under some pretty trying conditions.

The huge grassy plains are an ancient peneplaned surface. They are the almost level remains of a long eroded mountain range system that was later uplifted in a major tectonic movement of the earth’s crust known as the Kosciuszko Uplift thus forming the Kosciuszko Plateau.

The combination of cold air and flat topography created ideal conditions for natural high plain grasslands, technically referred to as the Northern Cold Air Drainage Plains. These were highly prized for summer grazing.

First stop, Witzes Hut. Witzes Hut, possibly a corruption of Whites Hut, like many Kosciuszko huts is set in a picturesque shelter belt of snow gums. Built in 1882 it is a vertical slab wooden hut, single room (about 6m x 3m) with a wooden floor and open fireplace. It is just one of many huts in Kosciuszko: cultural relics from the days of summer cattle and sheep grazing on the high plains.

They are invariably basic: shelters of last resort according to the NPWS signs tacked to the doors. Our late season crossing of the AAWT became hut dependant as the weather closed in. Although we had tents, it was a irresistible temptation for these warm-blooded Queenslanders to sidle into a snug dry hut at day’s end.

Day Two: Sunday 12 May: Hayburners of the High Plains: Witzes to Hainsworth Hut: 23 kms.

At 23 kilometres, a longish day beckoned. As a graduate of the Brian Manuel School of Bushwalking I had slyly insinuated to my friends that there was “no hurry” to pack up in the mornings. For those who have not been on the receiving end of this daily regime, expect a rousting out of your downy nest well before sunrise. About 5.00 am is Brian’s preferred time.

Unsurprisingly, a heavy frost carpeted the grass outside. Meanwhile, inside, my scouting friends Peter and John had worked their magic with two sticks, or whatever they use these days, and had succeeded in cranking up a fire of sorts. This we kept going until the last possible moment. Hut etiquette : Always make sure to thoroughly extinguish any fire before leaving the hut and replace firewood used.

On schedule at 7.30 am we scrunched off along the Bullock Hill Trail. Ghosts in the freezing mist, frost nipping at any gloveless paws. Before long the mist dispersed, revealing a brilliant blue sky and vast frosted grassy plains. Sunny with the max creeping up to a sizzling 13°C. Even the brumbies were out picnicking in the glorious autumn sunshine.

Brumbies aka Wild Horses aka Feral Horses

A brumby sighting is always exciting for those misguided equinophiles we were harbouring in our midst. But brumbies are feral horses, much the same status as foxes, cats, goats, deer and pigs. And as such they have no place in these fragile alpine ecosystems.

In the ACT they are regularly culled, but in NSW, herds of these hayburners cavort over the snowgrass plains with impunity: brunching on the juiciest alpine wildflowers, carving out innumerable tracks through the scrub and trashing alpine streams and swamps with their hooves.

The Parks service does allow horse riding in Northern Kosciuszko and provides horse camps with yards , water troughs, loading ramps, hitching rails and full camping facilities. From my observations recreational horse riders act responsibly in the alpine environment by keeping to designated management tracks and horse trails . Feral horses are a different matter entirely.

In an attempt to manage brumbies, a 2016 draft Wild Horse Management Plan recommended reducing numbers in Kosciuszko by 90% over 20 years, primarily through culling. That would have left about 600 horses in the park.

Naturally the NSW parliament ignored the advice of its own scientific panel so there was no cull. Instead, the NSW Deputy Premier John Barilaro hatched his own plan, the now infamous: The Kosciuszko National Park Wild Horse Heritage Bill 2018.

The bill would prohibit lethal culling because of the heritage significance of brumbies. I, too, can understand the cultural imperative of maintaining a small sustainable herd of brumbies but there are still serious questions to be answered about the environmental impacts of large numbers of brumbies. The NSW Threatened Species Scientific Committee has described the damage done by brumbies as a ‘key threatening process’.

Fortunately, sanity has prevailed and by 2025 culling was well underway and brumby reproduction rates had dropped below replacement levels.

Update on the Kosciuszko Brumbies