We looked out over the wide sandy bed of the Flinders River. On the opposite bank, a line of high white sandstone cliffs rose abruptly to the sky. And nestled on our side of the river, shaded by huge she-oaks and eucalypts, an encampment of seven pup tents. Our home for the next six days.

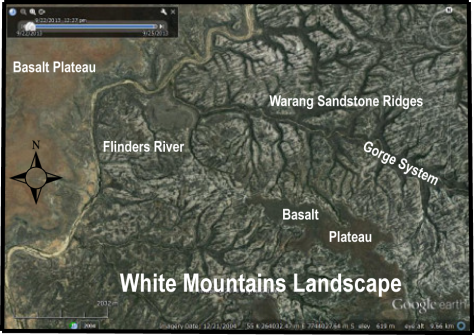

Inland from Townsville are the North Queensland Highlands, a remote and heavily dissected plateau rising to about 700 metres. This is the most extensive upland region in Queensland and forms the watershed of the eastward flowing Burdekin River, the southward flowing Thomson River and three rivers, the northward flowing Flinders, Norman and Gilbert, which empty into the Gulf of Carpentaria. The Flinders River, at 840 kilometres, is said to be the longest river in Queensland.

The White Mountains lie in the far SW corner of the highlands, 350 kilometres west of the coastal city of Townsville and just north of Hughenden, the home of the Flinders Discovery Centre which houses an impressive display of fossils from around the world including the local Muttaburrasaurus langdonii, a herbivore which roamed these parts nearly 100 million years ago. Hughenden is equally famous in paleontological circles for the Hughenden Pterosaur, a winged reptile that cruised the skies above seas and lakes of ancient Australia.

Near its headwaters the Flinders River has cut down through an uplifted block of soft Mesozoic sandstones, capped in places by a harder layer of Tertiary basalt flows. The resulting landscape is a maze of sandstone gorges, chasms, cliffs and clefts now protected in the 108,000 hectare White Mountains National Park. For much of the year this is an arid landscape, but when a good wet season arrives, vast swathes of native grasses turn green and the Flinders River becomes a torrent. The Flinders River was named by Lieutenant Stokes RN of The Rattlesnake in 1841 in honour of the great British navigator Matthew Flinders who completed one of the earliest maps of the coastline of Australia.

The White Mountains are part of the Desert Uplands Bioregion which accounts for about 4% of the area of Queensland. This not a true desert but has a semi-arid climate, thus has some desert-like characteristics particularly its low and highly variable rainfall regime. The annual average rainfall is a scant 490 mm, three quarters falling in summer from November to March. The period May to September has virtually no rain. The variability of rainfall can be described as extreme with annual totals as high as 800 mm when a good wet season kicks in. In a dry year the rainfall can be as little as 130 mm. Average maximum temperatures are a very hot 36°C in summer and a very warm 25°C in winter. Bushwalker John Milne, who was one of the first walkers to see the potential of the White Mountains wrote in the 1967 issue of Heybob (UQs Bushwalking Club Magazine) that:

“ Central North Queensland is a marvelous place, but see it in winter. The view in summer is hazed by clouds of bush flies and black native bees. The heat is intense on the treeless plains and the still, airless river flats are rather uncomfortable.”

Our walk was in early May, just after the summer rains had topped up the waterholes in the Flinders. But even in May walking on some days was still uncomfortably warm especially in the latter part of the week when maximum temperatures were consistently above 30°C.

The landscape is a mosaic of range, plateau and scarp terrain formed on undeformed coarse-grained Mesozoic sediments. The rock type is mainly siliceous sandstone and conglomerates; the freshly broken sandstone is white, hence I imagine the name, White Mountains. When wife Judy and I first looked over into this terrain a decade ago from a lookout above the nearby Porcupine Gorge I was so intrigued by this remote and wild landscape that I hoped that I could return one day.

So in 2014 I was back again with my hiking friends, Noel Davern (leader), Joe Kirkpatrick (chief organizer and 2IC), and the usual motley walking crew of Don Burgher, Alf Moore, Sally Clem and ‘straight–line’ Brian Manuel. This was a great opportunity to do some real exploratory walking in this remote and rarely visited part of Queensland. A combined Australian Geographic and Royal Geographical Society scientific expedition in 2001 described the White Mountains as a biological black hole, so little was known about the area.

It had all the hallmarks of exciting off-track exploring: isolation, great geology, aboriginal art sites, a fauna and flora very different from our home territory in SEQ, and a documented history of the brief early contact period between European settlers and the local Quippenburra clans.

I was particularly keen to see the rock art as it was still largely unknown until the 1980’s when Michael Morwood undertook some extensive field work in the Porcupine and Prairie Creeks, nearby tributaries of the Flinders. Close to our camp Noel had records of several sites of petroglyphs and stencil art.

Monday 5 May: Hike into base camp on Flinders River.

Our little convoy of two 4WDs set off on a ten hour drive into a cattle grazing property abutting the White Mountains National Park. After dropping off some fresh fruit for Jacko, the owner, and rigging up grass-seed netting over the radiators we puttered off, swerving frequently to dodge termite mounds which were sprouting up everywhere, even on the station tracks. An hour later we pulled up near an old cattle loading ramp, our starting point, about a kilometre short of the get-down over the escarpment. Lugging heavier than usual rucksacks we trundled off across a basalt strewn plateau clothed with open woodland: a sprinkling of ironbarks, kurrajongs and a dense ground cover of native grasses. The descent over the escarpment needed a bit of care but with an hour left before dark we found our campsite, rigged up our tents, collected wood and drinking water and then settled down around the now blazing fire on the sandy river bed. Noel and Joe entertained with tall tales of life in North Queensland involving characters with monikers like Peter No-Neck, Push-Bike Pete, Piggy or Bones and some names I wouldn’t care to repeat here.

Tuesday 6 May: The Rock Art Sites: 14 kms.

Awake to a cool clear morning. Noel was taking us to Aboriginal Rock Art sites that he knew about, one stencil site and one engraving site. At 8.00am sharp we set off upstream along the sandy bed of the Flinders River. Striated pardalotes “chip…chipped” from the river banks, a wedge-tailed eagle circled overhead, and a few hundred metres away a dingo lapped warily from the water’s edge before ducking into the undergrowth as we approached.

The first art site was a sandstone overhang decorated with a number of simple red ochre hand stencils, including a child-sized palm. These were similar to hand stencil art I have seen at Carnarvon Gorge, Moolayember Gorge, Mt Moffatt and Carnarvon Station, all in the Central Queensland Sandstone Belt. But hand stencilling is found over found over much of mainland Australia. Although in the Carnarvon and Mt Moffatt sites there are much more complex stencils including a full man stencil at The Tombs in Mt Moffatt. Nearby excavations from the Prairie Creek-Porcupine Creek systems show that aborigines occupied the White Mountains from at least 11,000 years BP.

After morning tea we explored up a minor tributary where Noel led us to an outstanding art site, the highlight of my trip, a sandstone shelf on a permanent waterhole. The site, 150 metres long by 20 metres wide was covered with hundreds of pecked engravings or petroglyphs. I recognized emu tracks, kangaroo tracks, boomerangs, snakes, hafted stone axes, human footprints including a scarily huge footprint. But most impressive were two large humanoid figures, one male and one female. The only engraving I was unable to identify was a star shaped symbol.

These were lightly pecked engravings where the surface patina had been pecked through to reveal lighter rock underneath. The presence of the hafted axe peckings indicate that the engravings are relatively recent, dating from less than 3,700 years BP.

But the traditional way of life halted abruptly around 1874, after a period of mutual violence by aborigines and settlers. Thus anthropologists have only sketchy information about the local Quippenburra clans. Michael Morwood’s Visions from the Past is an excellent reference book for anyone interested in Aboriginal Rock Art and it includes a detailed chapter on the White Mountains.

Wednesday 7 May: The Owl and The Red Fort: 11 kms.

Creatures of habit we swung out of camp at 8.00am. Another fine, warm day for our explorations. Immediately opposite our campsite we climbed up to The Owl, two oval shallow caves separated by a wall of dark sandstone… An owl? Well maybe, with some imagination.

Leaving The Owl on its roost we spent a very satisfying day probing our way southeast, along the high sandstone ridge which climbed to over 600 metres. With no time pressures we had ample opportunity for checking out the intricacies of weathering on this soft sandstone, stopping at spectacular vantage points for Noel to point out landmarks and for our photo buffs to do their thing.

The landscape was reminiscent of the Precipice Sandstone terrain of Central Queensland, but significantly more dissected and rugged. We were standing on exposed outcrops of Warang Sandstone (named after a nearby property) which were deposited in the Galilee Basin (think coal measures) during the Triassic some 235 million years ago. Consequently White Mountains is a landscape of sandstone cliffs, deep ravines, rocky ridges, overhangs, caves, arches and columns. On reflection, it also brings to mind the landscapes of Utah and Arizona in the USA.

I had read in an Australian Geographic article that hiking in the White Mountains is restricted mainly to the sand choked valleys, but Noel had a different take on this exploration business and carted us off along the high ridgelines, accessing areas seen by few bushwalkers.

The Red Fort, a small rocky outcrop or butte, is clearly visible from kilometres away. It is a residual of laterised sandstone emerging from the Warang Sandstone layer. During the Tertiary starting 70 million years ago, much of northern Australia was subjected to a humid tropical climatic regime. Under these high rainfall conditions iron accumulated steadily in surface rocks as other minerals are leached out, so that a hard iron rich crust developed, in a process called laterisation. The hard capping is sometimes called duricrust. These flat, hard capped sediments resisted erosion, hence The Red Fort now stands above the surrounding softer Warang Sandstones.

Roast lamb and baked veggies for dinner? On a hike? A culinary coup pulled off by Noel and his sous chef, Joe. But first, the small matter of hoofing back up the escarpment to the cars and returning with a cast iron camp oven, a leg of lamb, a bag of veggies, more wine, a mini shovel and the kitchen sink. Meanwhile, back at the ranch, Don had stoked the fire to ensure a good bed of coals. In my absence Alf supervised operations from my comfy Helinox hiking stool (a big hit with the rest of the crew), while Sally polished off yet another Sudoko. And our bush chefs rustled up the perfect camp oven roast leg of lamb complemented with potatoes basted in a sauce of meat juices and garlic.

Thursday 8 May: The Sphinx: 7 kms.

Awake early enough to see Venus still blazing brightly in the eastern sky. Another exploratory day, or to put a Noelian spin on it: “An easy walk along the ridges once we find an easy way up.”

But really nothing is straightforward or easy in this country. Our preferred mode of travel was along the SE trending open ridge lines but these are always bisected by the headwaters of deep erosion gullies which require some scrambling to bypass. The sandstone surface is crumbly and brittle and at the higher elevations capped by a sedimentary layer of abundant loose conglomerates. Just perfect for skidding on, as my bum found out.

Warmish conditions along the ridges today at 30°C plus, meant that Noel copped more than the usual ribbing about our walking conditions:

“Hey Noel…where’s the button for the aircon?”

“Hey Noel…what happen to our short breather?”

“Hey Noelie…how’s about a water stop?”

I have noticed that Noel’s smokos, morning tea breaks, lunch breaks, water stops or rests were always “breathers.” A North Queensland term perhaps? But always less than our regulation ten minutes.

After a good sticky-beak around, peering down into deep gorges, checking out all manner of sandstone arches, columns, overhangs, tunnels and the outcrop of The Sphinx, we scuttled back to base for a loafy afternoon of swims, clothes washing and copious mugs of black sugary tea and soups. Young Noel was clearly unfazed by the morning’s warm exertions and after a quick swim, beetled off up the escarpment carting back to the vehicles the heavy camp oven and his huge 20 litre magic pudding tucker box. This container would appear every meal time, and all manner of goodies would emerge. Milo and sachets of some dubious coconut rice concoction seemed to be a big mealtime hits with Noel. Like me, a lightweight hiker Noel is not.

Just on dusk a young dingo, Canis lupus dingo, emerged onto the river bed, paused and sniffed the air taking in the scent of our potatoes roasting in the coals of the fire. But before I could grab my camera it turned and trotted off downstream, jaunty like. While it had the usual dingo attributes( see photo below) of erect pointy ears, long muzzle, bushy tail and lean musculature, its coloration was very dark. Not the typical yellowish or ginger tinge. According to my dingo bible, Laurie Corbett’s “The Dingo”, black dingoes are quite a rarity. It appears that in the early years of European settlement black dingoes were more common, but are now less frequently seen. We had seen plenty of dingo tracks in the sand but no evidence that they were mooching around our camp at night. Still, I took particular care to park my hiking boots in the tent at night. There is that persistent hikers’ myth of dingoes loping off with walkers’ unattended boots in the dead of night, much to the dismay of the bootless hiker the next morning.

Friday 9 May: Exploratory: 14 kms.

For a change, an overcast and cool start. Noel carefully emphasized that today’s walk was: “exploratory…so take plenty of water and expect to be out all day.” We headed upstream for a kilometre, then swung up onto one of Noel’s easy ridges, searching out territory that Noel hadn’t explored on his previous visits. After a few kilometres of ridge-crawling came a pleasant discovery. We looked down into a very deep gorge system bounded by massive cliffs of Warang Sandstone. This we called The Chasm, on, naturally, Chasm Creek. Naming rights are one of the benefits of walking in remote areas with few features actually charted on available topographical maps. Here was a morning tea spot without parallel: clean rock slabs to sprawl out on, a cool breeze and impressive views vertically down into The Chasm. But don’t stand too close to the pie-crust thin cliff edges.

From here we worked our way northwards along the ridges, hoping to link up with a known exit ridge to get us back to the campsite via The Aerofoil and The Owl. Our plan nearly came unstuck. Ahead was a seemingly unbroken line of crumbling sandstone cliffs. Unsurprisingly, ‘Straight-line’ Brian sloped off to the nearest launch point closely followed by Noel. Hmmm… now what exactly did Noel say about coming prepared? I must have missed the bit about the 50 metres of climbing rope, helmet, harness, grappling hooks, Spiderman suction caps, plasma pack, spare body parts and the voucher for a free Royal Flying Doctor service evacuation. But, after checking out a couple of dubious lines, Brian declared it was a “no-goer.” A sigh of relief from the anxious troops perched on a nearby knoll. Naturally, a mere 100 metres further along the cliff line was a gully giving us an easy ride up and out onto our exit route.

We wandered off, line astern, without much thought to navigation. Inevitable consequence. Our landmark, The Red Fort, appeared on the skyline several kilometres to the SW of where we expected it to be. Fortunately, Noel and Joe are of new age navigator ilk, both incorrigible GPS “track loggers”, and had recorded a section of the return trip from a previous day’s walk. And so, late in the afternoon we pulled into camp and found that Alf, on an RDO (Rostered Day Off), had stacked all of our firewood into neatly graded billets and had the fire underway…sort of.

Saturday 10 May: Exit to Porcupine Gorge.

Our last morning at White Mountains. We set off back up the escarpment, turning at the top to look back over the territory we had covered over the past five days. And then it was off on the final stretch of our White Mountains odyssey, striding out across the high basalt plateau. But lurking in wait were several of Jacko’s long-horned scrub bulls. Ornery looking critters who trotted long with us, stopping every so often to eyeball the nearest walker.

Joe, who has clocked up many a kilometre in this cattle country, knew the drill and suggested we should release our rucksack chest and waist buckles ready to take the bolt for the nearest tree. The tree part puzzled me. What trees? There is a reason why botanists describe this landscape as open woodland. Hectares of tufted Flinders grass but not much in the way of trees. No matter, I wasn’t overly concerned as Noel was decked out in his favourite red bushwalking shirt and on his back, a dark red One Planet rucksack. These were, as the saying goes, like a red rags to a bull. And so ended a most satisfying exploratory walk in the White Mountains leaving us with another week to explore nearby Porcupine Gorge and closer to Townsville, the intriguingly named Puzzle Creek. But more of that another time.

Useful References:

Australian Geographic: White Mountains. Apr-Jun 2001.

Geoscience Australia: White Mountains 1:100,000 map.

Geoscience Australia: Hughenden 1:250,000 map.

W. Willmott: Rocks and Landscapes of National Parks of Nth Qld. (Geol. Soc. Qld, 2009)

D. Osmond: Ten Days in under 10 kg. Outdoor Mag. Feb-Mar 2005.

M. Morwood: Visions from the Past. (Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002).

Geographic Section Dept. National Development: Burdekin-Townsville. Resources Series. (Canberra 1972)