Wallangarra Ridge is a little visited section of Girraween National Park in Queensland’s Granite Belt. It is a spectacular landscape of granite domes, extensive rock slabs and giant balancing tors. The dominant vegetation is a low Eucalypt woodland still showing the fire scars from 2019 bushfire season. As the bulk of the walk is off-track , some navigation skills are needed.

by Glenn Burns

Girraween means ‘ Place of Wildflowers ‘

The Wallangarra Ridge sits at 1100 metres, while predictably cold in winter it was still quite warm during the day. Late March, 29 degrees centigrade. The scrubby vegetation made long-sleeved shirts and trousers a wise sartorial option.

The Parks website provides this irresistible description of the Wallangarra Ridge : “… breathtaking views sweep over to the Wallangarra township and distant rolling hills. Soak up the vistas of nearby Mallee Ridge, the giant monolith known as The Turtle and Girraween’s highest peak, the majestic Mt Norman…On a hot afternoon, cool breezes waft through the lush gullies between Mallee Ridge and Wallangarra Ridge . Listen out for the rustling of bell-fruited mallee…You’ll soon forget the gruelling climb! “

Geology

The geology of Girraween is not particularly complex. The area is the remnant of a pluton of Stanthorpe Adamellite ( a quartz monzonite ), which is a major unit of the New England Batholith, intruded as a molten mass in the Early Triassic, some 225 mya.

As the overlying rock was eroded the granite mass expanded setting up stress fractures forming regular rectangular joint patterns. These rectangular erosional jointlines had a strong influence on the development of Girraween’s landforms. Girraween’s domes, tors, rock slabs and rectilinear drainage pattern are typical of granitic landform assemblages throughout the world.

Sunday

After a long five hour drive from the coast we pulled into the Park HQ on a pretty warmish afternoon. A hurried lunch and we were heading south on the Castle Rock-Mt Norman track, more uphill than I wanted. Neither my fellow hiker, John, nor I were keen to haul in water supplies for two days of walking and camping so the plan was collect some on the way to Wallangarra Ridge.

Finding said water supply proved elusive as most gulleys and creek beds were dry. Surprising given recent rains in a strong La Nina season. But a little bit of detective work and some scrub bashing unearthed a trickle hidden in a glade of ferns. Enough to provide an initial five litres each. Tomorrow we would have to replenish the supply. But our 1:25000 topo map showed nothing in the way of perennial streams in our intended camping zone. All we had to do now was to haul the additional five kilograms on the 250 m climb to the The Sphinx and then to the track terminus at The Turtle. From here it was all off-track.

Navigationally, it was simply a matter of following our noses around the eastern cliff line of The Turtle and heading SSW along the 1100 m contour line. This involved a fair bit of bush-bashing and picking the easiest route between and around the large outcrops of granite. To avoid too much bush-bashing, we took to open rock slabs whenever the opportunity arose.

By late afternoon, our enthusiasm waning, we propped at a rare flattish patch of sand nestled between rock slabs and boulders and relatively clear of burnt out scrub. It was too late to go gallivanting around looking for the Wallangarra Ridge Remote Campzone still some one and a half kilometres to our South-West and 100 metres down in a decidedly scrubby looking valley. I’m not sure why camping down there would offer any positives.

After several cups of black tea to rehydrate, we ferretted out all our warm gear, donning trousers, thermals, fleece coats and beanies and wandered out to take in a spectacular a red sunset .

Our rocky eyrie looked out over the Queensland /New South Wales township of Wallangarra, some six kilometres to the south. In the far distance was the Roberts Range, marking the boundary of Girraween’s sister park, Sundown.

The Roberts Range

The Roberts Range is a 1000 metre divide that separates the Severn River to the north from its southern neighbour, Tenterfield Creek. Both are tributaries of the Dumaresq River. It is named after Francis Edwards Roberts, the Queensland Government Surveyor who was involved in the 1863 border survey together with his New South Wales counterpart , Isaiah Rowland. There are plans afoot to expand the Protected Area Estate in the Granite Belt to include the Roberts Range area and help link Girraween and Sundown National Parks. Another concept under consideration is a Border Walking Trail along the easement of the Qld – NSW border.

This easement is a well maintained 4 WD track that parallels the border fence, technically a Dog Check Fence. The walk along the fence line easement is a classic high range roller-coaster, up and down…up and down. A winter walk without parallel. But…believe me when I tell you that it is best avoided over summer. Read more about the Roberts Range walk at the end of this post.

Back on the Wallangarra Ridge we had no campfire. A cold WSW wind sent us scuttling off to our tents, lulled to sleep by forgettable podcasts and the occasional hooting of Boobook owls.

Monday

5.30 am . Rolled out to another crispy Granite Belt morning. John was already up, cranking up the stove for our coffee followed by a substantial bowl of thick creamy porridge. In my case, a tried and tested mixture of rolled oats, raw muesli, sultanas, plump dried apricots, shredded coconut and lashings of powdered milk. Fuelled up, we were up and running ( walking ) by 8.00 am.

Today was off-track to reach the high point of Wallangarra Ridge SSW of our campsite, as the crow flies. If only we were crows. We had read somewhere that the summit is marked by a small rock cairn, from which we were promised extensive views across the park and down to Wallangarra township.

But first… find some water. Our thought bubble of siphoning and filtering stagnant water from shallow pits and pans ( sometimes referred to as gnammas ) in the granite didn’t appeal.

But the gods smiled. Several La Nina seasons meant that we stumbled across a trickle in nearby swales. No more than 500 metres downhill from our camp. Pretty unusual.

The swales are clothed in ‘Gully’ open woodland which develops in sheltered run-off situations. I identified a few of the scorched dominants: Banksia spinulosa, a Callistemon sp , Eucalyptus brunnea and a dense regenerating understorey.

From the scrubby swale our line of travel took us out and up onto our morning tea vantage point where we propped in the shade at the top of a series of rock slabs stairs. A short distance to the west we could make out the highest part of Wallangarra Ridge . John scanned along its skyline with his telephoto lens until he located a mini summit cairn. Behind us and off to the north were easily the best views of The Sphinx and Turtle in the whole park.

Twenty minutes later we stood on the summit boulder at about 1140 metres. To our south was Bald Mountain ( 952 m ) and six kilometres in the distance was the border town of Wallangarra.

Wallangarra

Wallangarra is a small town of 500 on the border of Queensland and New South Wales. It grew up close to the site a 1859 border survey marked tree, indicating the border between Qld and NSW.

It is on Ngarabal country with Wallangarra said to mean ‘ lagoon’. I have read that wallan means water and guran means long. Long water as in billabong or lagoon.

Meanwhile, back on Wallangarra Ridge, we drifted off northwards down the toe of the ridge in search of the mythical official Wallangarra Ridge Remote Bush Camping Zone. Unsucessfully. After an hour of thrashing around in the dense regrowth in the vicinity of the GPS coordinates provided, we gave up. Anyway, there was no chance a slotting a tent in this stuff. Bit of a navigational mystery actually. According to the Parks website … ” there is no defined camp site and access is via difficult cross country walking “. We turned for home, intent on finding enough water to see us through another day.

Back at the ranch we settled in for a decidedly leisurely and late lunch, several brews of hot black sweet tea and a nanna nap in the shade. Though the latter was moveable feast as we searched for the deepest shade.

Come late afternoon, John sloped off, camera on alert. No doubt off to hunt down any unsuspecting Lyrebirds and Button Quail which he was convinced were scratching through the heaps of leaf litter. Meanwhile I wandered around checking out all the nearby rock slabs hoping for anything of geologic or botanic interest .

The Superb Lyrebird

( Menura novaehollandiae )

On a previous trip to Girraween we had been fortunate to see and hear Lyrebirds at nearby Mt Norman, so weren’t surprised to hear them again close to our campsite.

The Lyrebird is one of nature’s best mimics. It can imitate a variety other bird species such as cockatoos, butcherbirds and whipbirds. But it doesn’t draw the line at bird calls. It can reproduce the sound of saws, guns and engines.

One Lyrebird story I read happened at a Victorian timber mill. The mill used three blasts of a whistle to signify an accident and six blasts to notify a fatality. One day the local Lyrebird blasted out six whistles, no doubt creating considerable workplace disruption.

I have been tricked by a Lyrebird mimicking the sound of a ‘reversing’ truck. Our hikers’ camp in Sundown National Patk was hidden in scrub with a small 4 WD campround nearby. The sound of a ‘reversing’ vehicle at the 4 WD campground attracted our attention as it had persisted for well over fifteen minutes. I waddled up to check things out, thinking perhaps a 4 WD had bogged or some such problem. No vehicle in sight but the ‘reversing’ sound continued from the undergrowth. The mystery of the phantom 4 WD camper was solved. Lyrebird.

Interestingly, scientists know that some mimicry is of now extinct species, passed on from parent to chick over the generations.

Another sunset worthy of the ABC TV weather report , a decent feed, a chin wag and it was all over for today. My Macpac micro green tent beckoned.

Tuesday

5.30 am. Time to roll out into the pre-dawn twilight. My pocket thermometer hovering on 10o C with a cool Southwester riffling across our campsite. A bite to eat then we struck camp, packing our gear and leaving tents out to dry.

Our walk today was off to our east onto an unnamed adjacent ridge, aligned in the same NE/SW configuration as the Wallangarra Ridge. At 1220 metres it is nearly 100 metres higher than Wallangarra Ridge and more densely vegetated. The attraction was that from its summit we should be able to see across to the complex that makes up Mt Norman ( 1266 m ) and the Mallee Ridge ( 1230m ). Maybe our Girraween sojourn .

Our line of travel took us initially over lower rock slabs then climbed into mature stringybark forest, habitat for a Wallaroo, a large furry macropod, which took off when we disturbed it. We wound in and out of huge granite boulders before fetching up on a narrow summit plateau at 1200 metres. Perched on the plateau were jumbles of huge tors topping out at over 1220 metres. Naming rights… Wallaroo Ridge.

Wallaroo aka Euro

Our Wallaroo ( Osphranter robustus ) was, as the specific name implies , sturdy ( and shaggy-coated ) . They are generally solitary and nocturnal. The Eastern Wallaroo is not on the threatened species list and has an extensive territorial range in Australia’s Great Dividing Range.

We scrambled to the top of the highest tor for morning tea. Now we had impressive clear easterly views to the domes of Mallee Ridge and Mt Norman. Mt Norman was named after Sir Henry Norman, Governor of Queensland from 1889 to 1895.

Getting to the Mallee Ridge and thence to Mt Norman from here looked like a hard slog. Maybe one for the future. Fortunately, there is an easier way, from the Mt Norman track. Although the twin domes ( 1230 m ) at the SW end of the ridge looked a tad formidable. My Hema Girraween map describes the walk as… ” easy rock slopes “. I live in hope .

Bell-fruited Mallee & the Mallee Ridge

While traversing the lower rock slabs, we had spotted a line of Bell-fruited Mallees growing in a jointline which had retained a bare minimum of mulch that was enough to sustain a viable pocket of Mallees.

These were the mallee Eucalyptus codoncarpa , that also grows on the nearby Mallee Ridge, and after which it was named. In Girraween, the Bell-fruited Mallee is only found on Mt Norman and rocky outcrops to its west and south- west. Despite its somewhat restricted distribution in Girraween it is listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as being of ‘least concern.’

Morning tea rest over, we backtracked to our campsite where we polished off our lunch leftovers and the inevitable mug of tea. With a final check of the campsite, we hoisted up the monkeys and waddled off for a leisurely afternoon’s walk back to our overnight camp at Bald Rock Creek campground.

One of the attractions of poking around offtrack is that little surprises form part of the experience. This time we chanced on a high ledge festooned with a mass of rock orchids and then further on, an unusual find, a Bootlace Orchid.

The Black Bootlace Orchid

The Black Bootlace Orchid ( Erythrorchis cassythoides ) is a leafless climbing orchid. It has thin, dark brown to black stems that climb up to five metres up tree trunks. The Bootlace has displays of 10 to 30 yellow to green flowers. Surprisingly, a Bootlace popped up in my suburban native garden in SEQ, lasted several years, then died back for no reason that I could figure out.

The Bootlace was first described by Richard Cunningham who sent his specimen and descriptive notes to his brother, the explorer Alan Cunningham. Alan Cunningham forwarded the description on to the the English orchidologist, John Lindley. Richard Cunningham had originally named it Dendrobium cassythoides but it was later renamed as E. cassythoides.

By 4.00 pm we were setting up for our final night in the civilised surrounds of Bald Rock Creek Campground. Although this had been a short visit to Girraween, we had explored a little visited section of this outstanding granite park which I had always been keen to investigate. Coming up next year … the Mallee Ridge.

A description of one of my walks on the Roberts Range

The walk is the classic high range roller-coaster starting at 1067 metres, dipping and rising: 973 m, 1039 m, 1030m, 1015m, 1087m and reaching 1120m at our final climb before turning off and descending to the Sundown Road.

Climbing up to our first high point, Hill 1067 we passed into a special habitat, a high altitude forest, restricted to the very highest parts of Sundown and the Granite Belt.

This is open forest, dominated by Silvertop Stringybark (Eucalyptus laevopinia), Yellow Box (E. melliodora) and the best name of all, Tenterfield Woollybutt (E. banksii). Silvertop Stringybark and Tenterfield Woollybutt are interesting in that they are disjunct populations of the same species growing further east at Lamington and Mt Barney.

It is likely that they survive here on traprock because of the cooler, misty micro-climate on the highest points of the Roberts Range. Further along the range, on the summits of the highest hills at 1087 metres and 1120 metres, we passed through more small patches of high altitude forest.

As we climbed to the final high point at 1120 metres we entered a designated ‘essential’ habitat. These are areas meant for the protection of a species that is endangered or vulnerable.

In this particular case the species was the Superb Lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) neither seen nor heard by our party. The Superb is the King of Karaoke and is such a good mimic that the bird being copied cannot tell the difference. The male Lyrebird has a repertoire of 20-25 other bird songs as well as mimicking car engines, chain saws and even barking dogs.

When Queensland was proclaimed a separate colony on 6th June 1859, Surveyors Roberts from Queensland and Rowland from New South Wales were sent to define the boundary between Queensland and New South Wales from Point Danger to the Dumaresq River.

They started work in 1865 and worked separately using their own instruments. As their traverse lines were different the defined border appeared in different positions. Ultimately the Roberts survey was accepted and this was the line depicted on our map and that we were following today.

I was keen to find any relics of their traverses such as rock cairns or horse-shoe blazes on trees. I found one old blaze, indecipherable, so there is no evidence that it was part of the border survey. It would be interesting to do the entire Roberts Range traverse with data from Robert’s original field book.

Roberts, an Irishman, trained as an engineer and in 1856 he became surveyor of roads for the Moreton Bay District later gaining a post as a surveyor with Queensland’s Surveyor-General’s Department in 1862.

Colonial surveyors were tough, capable bushmen able to endure considerable hardship: life under canvas, poor food, heat, flies, arduous travel and isolation. Unsurprisingly, it was a constant struggle to stay healthy.

Queensland colonial surveyors could be struck down by any number of health hazards: Barcoo Rot, Bung Blight, Sandy Blight, Dengue Fever, Malaria, snakes and crocs. Francis Roberts escaped all these only to die prematurely of sunstroke in 1867, aged 41.

Today, the border is marked by a Dog Check Fence; an outlier of the mighty 5,412 kilometre Dog Fence that runs from Jimbour in Queensland to the Great Australian Bight in South Australia. The Dog Fence is said to be two and a half times the length of the Great Wall of China and is easily visible from space. Our 1.8 metre high Dog Check Fence or Dingo Fence is a relic of an intricate maze of some 48,000 kilometres of interconnecting vermin fences built to keep dingoes and bunnies at bay. Unsuccessfully.

Other walks in Girraween National Park and nearby Sundown National Park.

Sunset at Sundown. Southern Sundown National Park. Qld.

By Glenn Burns

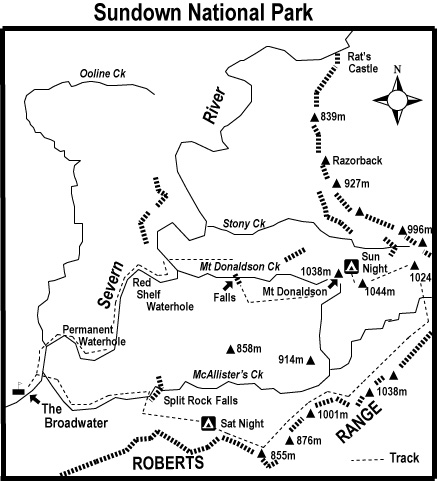

The following account is of a three day bushwalking circuit that I did with two friends in southern Sundown National Park in which we followed up McAllisters Ck, a deeply incised tributary of the Severn River. From McAllisters we ascended onto the Roberts Range at about 900 metres. After a long hot walk along the high Roberts Range we turned westwards pushing through dense undergrowth to overnight on Mt Donaldson at 1038 metres. The following day we descended back into the Severn River.

In early October, walking friends Frank , Don and I completed a three day bushwalking circuit in Sundown National Park taking in some very interesting and challenging landscapes on the way. Although only thirty kilometres from Girraween as the crow flies, Sundown has little in common with the benign rounded tor landscapes of the Stanthorpe Granites.

Sundown offers a terrain of deeply incised creeks, gorges, waterfalls and steep stony ridges rising to 1000 metres. It is an inhospitable environment, dry and rocky. To me, a landscape reminiscent of the MacDonnell Ranges of Central Australia. Early settlers described it as “traprock”, geologically incorrect but an apt descriptor all the same. Traprock is a term applied to basalt landscapes in the UK while Sundown’s surface geology is predominately sedimentary which has been altered by heat and pressure (termed: metasedimentary).

Photo Gallery

Our trip followed an anticlockwise circuit: from the Broadwater up the gorge-like McAllister’s Creek, to Split Rock Falls; a climb to the Roberts Range at 800 to 1000 metres; a major scrub bash to Mt Donaldson (1038 metres); a steep descent to Mount Donaldson Creek and the spectacular Donaldson Creek Falls and a return down the boulder choked Severn River to the Broadwater Campground.

Geology of Sundown National Park

Sundown’s stony terrain had its origins in the Carboniferous Period (360million – 286 million years ago). Sediments from a volcanic mountain chain on the eastern edge of the Gondwana continent were deposited on the continental shelf and later avalanched onto the deep ocean floor.

The sediments formed thick beds of sands, silts and mud. Compression and deformation of the beds resulted in the metasediments of the Texas Beds. The predominate rock types of the Texas Beds are Argillite and Greywacke. Argillite is a dark grey/black mudstone, very fine grained and extremely hard. Greywacke is a coarse grained sedimentary of mixed composition, also very hard. These were later uplifted to a mountain chain, the remnants of which form the tilted hilly ridges of Sundown.

DAY ONE

McAllister Creek Gorge

We left Broadwater mid afternoon and rock hopped up McAllister Creek to Split Rock Falls. Here the creek was deeply entrenched in a narrow red gorge, defying Frank’s GPS to find the requisite number of satellites.

Following Don’s confident lead we hung from cracks and crevices, teetered along dubious ledges, finally reaching the barely trickling “split” falls, impassable…. of course.

Our bypass was a steep scrabbly climb on the spine of a rocky ridge to our campsite in a cypress pine grove at 800 metres. One of the very few open areas in an otherwise very stony terrain.

At 6.30pm, on sunset, we downed packs and settled into our campsite, complete with its own comfortable log seats and frug of whining mosquitoes. I soon lost my desire to join the “sleep under the stars” contingent as a full moon rose and the mosquitoes settled in for the duration. Instead I retired in comfort to my insect/moonlight proof “Taj Mahal”.

DAY TWO

Roberts Range

Our traverse along the crest of Roberts Range on the second day followed one of the ancient ridges. The Roberts Range was a roller coaster of elevation gains followed by steep descents. Hot work. Incredibly, we found two small dams high up in the catchment where we could replenish our water supplies and wash. Mid afternoon we swung off the Roberts Range heading for Donaldson.

Mt Donaldson

Progress faltered to about one kilometre an hour and visibility fell to ten metres as we pushed through unpleasantly dense thickets of Peach Bush (Ehretia membranifolia) and Cough Bush (Cassinia laevis). On occasion, one of our trio would disappear into a thicket failing to re-emerge after an appropriate wait. Several cooees usually provided the necessary geographic re-orientation and a bleeding bruised body would come flailing through the undergrowth, in due course.

On the summit of Mt Donaldson on our second evening we found some younger Permian breccias on top of the Texas beds. Breccias are sedimentaries composed of coarse, angular fragments of older rocks. My guide book implied fossil shellfish aplenty these outcrops. Even Blind Freddy should find one. The breccias were obvious enough but the fossils weren’t. Unfortunately, my conscience wouldn’t allow me to shatter rocks to find them, tempting though the prospect was.

As the sun set we perched on rocky benches above the cliffline and took in the view. This is reputed to be the best vantage point in the park, not an exaggerated claim. A rugged landscape unfolded: Donaldson’s northern summit was fringed by massive cliffs; stretching off to the north east was the Razorback (Berchtesgaden on my map) a ridgeline of numerous 900 and 800 metre hills grading down to the Rats Castle (a granitic dyke) on the Severn River, four kilometres away. Immediately below was the Stony Creek valley, lined with numerous scree slopes of shattered boulders. My track notes advised that walkers should not be

“tempted to descend Stony Creek since it is strewn with large boulders.”

On a distant western cliffline a trip of goats skittered along a narrow ledge, intent on finding a night bivouac in the thick brush.

DAY THREE

With the Stony Creek warning in mind, we left Mount Donaldson at 5.30am, chased off the summit by gale force winds and a suspiciously thick cloud bank building to our east over Stanthorpe. We descended steeply into Mount Donaldson Creek. Here we rewatered, dropped packs and headed downstream to inspect Donaldson Creek Falls, developed on resistant strata, with its 100m drop towards the Severn River.

The views down a red canyon to the Severn did not disappoint. Saddling up again we bypassed the falls and descended 230 vertical metres to the Severn River Flood Plain. The bed of the Severn is confined to the NNE trending Severn River Fracture Zone.

It is interesting that the river has not diverted around the harder Texas Beds but has continued to cut down into the resistant metasediments. Consequently, for such an old land surface the sinuosity of meander looping of the Severn is remarkably undeveloped. The sinuosity ratio for the Severn in Sundown is 1.04; very close to the ratio for straight, younger streams such as the Johnstone River (North Queensland) which has a ratio of 1.00.

A stream channel on a flat flood plain will often have a ratio of 3.00 or more (technically described as tortuous). Still, this was all useless palaver as we hoofed the final six long hot steamy kilometres along a rough, bouldery river bed to our final destination at Broadwater.

My thanks to Frank and Don for their invitation to join them on the Sundown trip and for some great navigation and geology.

References:

Willmott, W, 2004: Rocks and Landscapes of the National Parks of Southern Queensland.

Mapsheets:

Sundown National Park 1:50,000 ( Hema Maps)

Mount Donaldson 1:25,000

Mingoola 1:25,000

Artists Cascades

by Glenn Burns.

This pleasant little ramble is just the thing for walkers in Queensland’s hot and humid summers. Artists Cascades are a small set of falls and cascades on Booloumba Creek in the Conondale National Park, part of the Sunshine Coast’s forested hinterland. Although you could make this a short rock hopping trip, the numerous crystal clear pools are an ever present temptation for walkers to linger as they make their way upstream.

My five walking friends Alf and Samantha(leaders) and hangers-on Brian, Leanda, Joe as well as yours truly, left the Booloumba Creek Day Use Area soon after 8.30am, a bit of a late start for an overcast, humid but decidedly warmish November day. The walk is only four and a half kilometres to the cascades with an easier but slightly longer return leg on the Conondale Great Walk Track.

A pretty relaxed day, all in all. In days of yore, before the advent of formed tracks, the Booloumba Creek walk was a different proposition. Hairy-chested bushwalkers generally entered a kilometre upstream of Artists Cascades at Booloomba Creek Falls near a feature called The Breadknife, an impressive blade-like slab of foliated phyllite, a flaky metamorphic rock. Below it, in a leap of faith, walkers would drop into Booloumba Creek for the start of the swim down through Booloumba Gorge. As my 1980’s bushwalking bible “Bushwalking in South-East Queensland” noted: “… the descent route in Booloumba Gorge… should only be tackled by competent scramblers.” Over nearly a full day walkers swam, floated and rock hopped down past Kingfisher Falls, Frog Falls, Artists Cascades to exit at the day use area, occasionally bruised and battered. Altogether a very satisfying little adventure.

Our walk was a modest affair by comparison. Initially, it starts as an easy amble on a flat gravelly creek bank, but as the walk closes in on Artists Cascades, the walking changes to rock hopping. On the way up we passed a number of beautiful clear deep pools, ripe for swims and more swims. Booloumba Creek is set in sub-tropical rainforest. Some of the emergent species which I recognised included hoop pine Araucaria cunninghamii, piccabeen palm Archontophoenix cunninghamiana, bunya pine Araucaria bidwillii, flooded gum Eucalyptus grandis, black bean Castanospermum australe, and the strangler fig Ficus watkinsiana.

As an afficionado of the Booloumba Creek run I had come prepared, decked out in board shorts, quick dry shirt, track shoes in place of my Rossi heavy duty boots, nylon day pack with other hiking paraphernalia sequestered away in a dry bag. A pair of spiffy goggles found at a nearby a swimming hole enhanced my aquatic ensemble. No need to change into togs…sorry… bathers for you non-Queenslanders. Just flop or dive in.

Not unexpectedly, we crossed paths with a lethargic snake, a rather large carpet python curled up and in no mood to move. As with all snakes, the golden rule applied: leave well alone, even though pythons are fairly harmless. Snakes are always a consideration in the Conondales so some of us were sporting knee length, heavy duty, canvas gaiters.

Fortunately, heavy flooding over the past two summers had cleared the dense mist weed (Ageratina riparia) from the creek bed, making it much easier to hop from rock to rock and to spot the odd sunbaking reptile or three.

Around lunchtime we made our way onto the rocky benches surrounding the Artists Cascades. These smallish cascades drop into a deep inviting rock pool. But we needed no invitation and were soon frolicking around in the refreshing cool, clear water.

Revived, we tucked into lunch, allowing us time to start drying before squelching off on the five kilometre return leg along The Conondale Great Walk Track. If you have time I recommend you sidetrack to the old Gold Mine site and also find the short track to the “Egg”. The track was unmarked for a long time at the request of its creator but common sense prevailed and now it is well sign-posted. The construction of The Egg morphed into a political hot potato. The Egg is a $700,000 wilderness sculpture commissioned by the Queensland Government in 2010, and designed and built by Scottish artist Andy Goldsworthy. But more on that contentious issue another time.

Much of the conservation battle to save this relatively pristine area of South-East Queensland from further logging and mining was undertaken by the local Conondale Range Committee for which the bushwalking and camping fraternity can be thankful. If you are wondering about the origin of the name Booloumba as I did, my friends in the Conondale Range Committee provided the following information. Booloumba is aboriginal, from the dialect of the Dullumbara clan who were part of the Gubi Gubi language group. It is pronounced and spelt Balumbear or Balumbir and means butterfly; sometimes extended to mean place of the white butterfly. The national park name, Conondale, derives from Conondale Station, named by pastoralist D. T. MacKenzie in 1851 after Strath Conon in Scotland.

Photo Gallery

To Borumba and Back

by Glenn Burns.

The Mt Borumba circuit. A golden oldie. Just like some of the nine of us who lined up for this enjoyable ramble through the Imbil State Forest in South East Queensland to the fire tower on Mt Borumba. The 11 kilometre circuit, mainly on forestry tracks in the Yabba and Borumba logging areas, starts with a steepish climb. Then it wends its way gently uphill for another three and a half kilometres, first through park-like open Eucalypt forest and as it climbs towards the summit, it enters the cool shade of mature rainforest. The summit is topped by a decidedly rickety wooden structure known as the No.8 Fire Tower, now ringed with security fencing. The return trip, mostly downhill, features a gravelly descent and then a soggy track out to cattle yards.

Meanwhile back at the start of the walk our little band had formed up, my good bushwalking mate Brian Manuel in the lead. A quick vault over the locked gate and then up the dozer line that climbs vertically for The Beacon at 423 metres, an altitude gain of nearly 300 metres in one and a half kilometres. This must have been one intrepid dozer driver, no pussy footing around with zigzags, contouring or switch backs. Just straight up. And as I tottered my way up, one of those pesky elderly hares bounded by, calling out: “A good heart starter, hey”. No doubt about that. Fortunately for me, Brian called time, a welcome smoko break on the summit of The Beacon. A grassy glade shaded by gnarly old bloodwoods, a cooling breeze, fantastic views and a good feed.

On a crisp autumn day like this we had extensive views over Lake Borumba and the Yabba Creek catchment to the west. To the east and south were the high rugged hills and deep valleys of state forests, a verdant patchwork of rainforest, wet and dry sclerophyll forest, and plantations of hoop and bunya pine. These hills, now little more than 400 metres elevation, are the remnants of an ancient mountain chain planed down to a dissected plateau. The hard metamorphosed sediments, the Amamoor Beds, have resisted erosion, thus forming the elevated ridgelines that we were now following. Forestry areas are always full of places with tantalising names and intriguing stories to match. Names like Breakneck Road, Derrier, Little Derrier, Tragedy, Buffalo and Gigher. One of my favourites was on a faded little sign outside Imbil which said: “The Foreign Legion.” Not as in French Foreign Legion but an encampment of 150 displaced persons from World War Two. Known generically as “The Balts”, they came mainly from Eastern Europe, few speaking English, and were allocated plantation work at one of three camps: Sterlings Crossing, Derrier and Araucaria. The Balts lived a hard life in tent camps without electricity and running water. The children had a different take on any perceptions about hardship: “It was the best years of my life. We kids were allowed to run riot through the bush…It was simply fantastic.”

After The Beacon, we briefly took to a cattle pad before dropping down onto the Beacon Road. The route now meandered along forested ridgelines at about 400 metres, winding inexorably upwards towards Mt Borumba. Through gaps in the trees we caught occasional glimpses of the Borumba tower which was number 8 in a network of more than 30 fire towers spread across South East Queensland’s forestry areas. This 20 metre, three storey tower and its neighbours No.5 Mt Allan, and No.12 Coonoon Gibber, were used to fix the location of fires by triangulation. Interestingly, a large number of these fire towers were built by a Sunshine Coast resident Arthur Leis, all in days before fancy construction gear. Some of the higher towers like Jimna (47 metres) took Arthur three years to construct. No. 8 is a four -legged tower built in 1958, but variations included a three-legged tripod and the cheapskate model with boards nailed to a tree trunk. You can read more about Queensland’s fire towers in Peter Holzworth’s: Silent Sentinels: the story of Queensland’s Fire Towers.

It was not long before we swung south onto the No 8 Tower Road, as did a battered old 4WD ute, which caused a ripple of expectation among those of us plodding along in the rear. I recalled with deep fondness bygone days when said ute would grind to a halt and its driver, fag glued to bottom lip, would beckon walkers over: “Everything OK?”. A longish chat about the weather, cattle prices or his bee hives, and then our Good Samaritan would say: “Wanna lift?” This was the signal for us to pile in. But our latter day 4WDer merely glided past, stopping occasionally to nail up ever more Horses Ahead signs in preparation for an Easter horse endurance ride.

At the intersection with Borumba Mountain Road we swung west and climbed the final kilometre to the summit. As a veteran of Brian’s many forays into peak bagging I knew not to get overly excited about the possibility of majestic views over golden plains extended. And so it was. A view obscured not by the usual wreaths of claggy mist nor by sheets of bucketing rain. Just a wall of trees. Still it was a thoroughly pleasant spot for a lunch break: plenty of shade, grass to stretch out on and time to cast a covetous eye over one of Kiwi Ross’s mouth watering lunches. Take a chunk of crusty bread, add layers of rich red sliced tomatoes and then haystack the top with several acres of fresh alfafa sprouts. Joe to Kiwi Ross who was just about to sink in the tooth: “Hey, Ross. Would you like me to run the mower over that lot before you eat it?”

The inbound trip involved some backtracking for two kilometres until Brian suddenly executed a sharp left, and then plunged down an ever steepening trail mantled with loose gravel. Marbles on tiles. Believe it or not, the best strategy is to jog down, skating over the top of the rolling gravel, just like those flocking sheep on NZ high country sheep runs. Michelle, Brian and Kiwi Ross, who are skilled exponents of this arcane ovine art, arrived first, fully intact. For the rest of us it was a matter of gingerly picking our way down, unfortunately not without mishap to a derrière or two. And then came the trudge along a sodden track before fetching up at the cattle yards. Leaving plenty time to scrape off the mud and head off for cold beer, coke or water at the Railway Hotel, Imbil. My thanks to Brian (leader), and fellow Borumbians Alf, Joe, Ross, Linda, Michelle, Robyn and Samantha.