by Glenn Burns

Thirty kilometres off New Zealand’s southern coast, and separated from it by the stormy waters of the Foveaux Strait, is the island of Rakiura… Land of the Glowing Skies. You may know it as Stewart Island. In 2002 Rakiura became New Zealand’s 14th national park with 83% or 140,000 hectares of the island protected.

Rakiura’s NW Circuit is a challenging ten day, 125 kilometre track that covers some of the island’s best coastal scenery and ecosystems. The Lonely Planet’s Guide to Tramping in New Zealand describes it thus:

“This is the classic tramp on Stewart; the famous mud and bogs of the island make this track a challenge but, for trampers with time and energy, the isolated beaches and birdlife make it all worthwhile.”

While our three person team of Brian (leader), Sally and I found the ten days physically demanding, the compensations were ample: a rugged cliffed coastline, unsurpassed views from Mt Anglem and Rocky Mountain, excellent sightings of the island’s birdlife, and the green abundance of its ancient Gondwanan forests. Plus, we were pretty chuffed at our tenacity in completing the whole walk. No ignominious water taxi exits or food dumps for this trio of aged trampers.

Photo Gallery:

Maybe you are thinking of a quick dash around the NW Circuit next tramping season? Here are some tips to get you on your way:

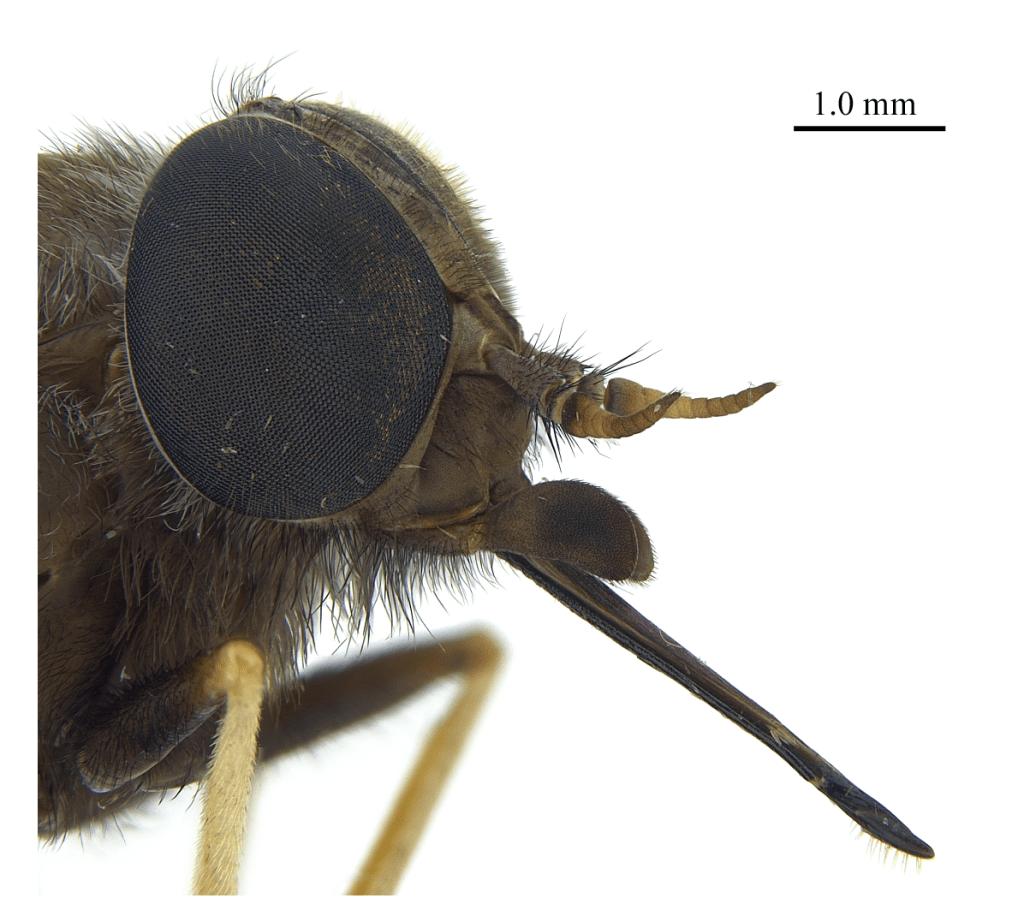

No snakes, spiders, ticks, leeches and not much in the way of other creepy crawlies. Notices in several of the huts informed us that earthquakes and tsunamis were a possibility, albeit long shots. Flooding of creeks and swamps are definite possibilities, while the tides wait for no man. So check your tide times if you don’t want to sit around for hours waiting for that ebbing tide. Those Kiwi midges aka sandflies are an ever present pain in the butt, like their Kiwi owners(Just kidding). The Department of Conservation (DOC) has rigged the huts with insect screens which keep the biting bumble bees in and the midges out. Deer hunters are often stalking around in the brush in their camo gear so you mightn’t see them. You might hear the report of their rifles but by then it’s probably all too late.

The Track:

The NW Circuit follows old deer stalker pads which, unfortunately, have degenerated into long sections of either boggy mud or surfaces matted with tree roots or slippery descents into the

innumerable creek crossings. There is an awful lot of tramping up and down over country which DOC brochures describe variously as ‘undulating’…not too bad. ‘broken’… not good news. But when you read that tomorrow’s section is seven hours over track that is ‘steep and often slippery’ you have hit the Kiwi tramper’s jackpot. Here’s a tip: don’t leave home without your walking poles which are a big plus for negotiating the uneven and slippery surfaces .

Walking Times vs Distances:

We quickly realised that the standard Oz three to four kilometres per hour is not a reliable estimate for this terrain. Fortunately each section has a nominal time and our experience was that these were pretty much spot on. Add another hour for lunch stops and rests on the uphill grinds. Younger and fitter walkers should bump an hour off the 6-7 hour sections.

Weather:

Rakiura has a well deserved reputation for rainy weather. It has a cool temperate climate with temperatures ameliorated by the effects of a warmish ocean current. Thus there are few extreme weather events apart from the nuisance of a near constant westerly wind drift. But it is a wet place with 1000-1600 mm of rainfall and 275 rain days per year. Thus of our eleven days on the track in March we expected seven rain days, but it only rained on three. The precautionary principle dictates a spare set of dry-bagged clothes for use in the hut at night and a good quality long rain jacket.

Huts:

We stayed in DOC huts each night, nine in total. For Australian bushwalkers used to high country cattle huts they are a culture shock: sturdy construction, draught proof, sporting uni-sex bunks, mattresses, stoves for heating, running water, tables, stainless steel sinks, toilets and insect screening. BYO sleeping gear, gas stoves, cooking utensils and earplugs. The bee’s knees.

Port William and Mason Bay huts were over-run by all manner of pesky types but other huts provided quiet refuges, some with views to kill for: Yankee River, Long Harry, East Ruggedy and Big Hellfire. The Tasmanian government would do well to emulate the modest design and egalitarian philosophy of these inexpensive but clean and functional tramping huts in preference to the expensive commercial abominations now visited on the Three Capes Track of the Tasman Peninsula.

Solo Walking:

I personally wouldn’t recommend going solo, though heaps of trampers and backpackers do. Conditions on the track can be treacherous, especially in wet weather. In the previous tramping season four trampers were evacuated with busted limbs. You could sit for many hours before another party came through so take advantage of the PLBs and Mountain Radios hired out by the DOC office in Oban. It is advisable for walkers to file an intentions form with AdventureSmart: ‘Safety is your responsibility. Tell someone your plans…it may save your life.’

Link: http://www.adventuresmart.org.nz.

Natural History:

Rakiura is a rugged forest-clad island. Walkers get to experience avariety of landscapes ranging from cool shady forests, isolated beaches, quiet inlets, high sand dunes, sub alpine peaks, glacial tarns through to immense windswept tussock lowlands. But much of the walk is spent in Podocarp and mixed hardwood forest dominated by Rimu and Kamahi with sub-dominants of Rata and Miro.

Birdlife:

Birdlife is more abundant than on the mainland and so with a little luck the observant tramper will glimpse a kiwi of the feathered variety: the large Stewart Island brown kiwi. Ample reward for many hours of slogging along Rakiura’s muddy tracks. And you are lucky to see any bird life because like Australia, NZ has an unenviable record of feral pest invasions. Try deer, rats, stoats and an uniquely Australian contribution, the possum. Fortunately DOC has an ongoing program of trapping and poisoning. Trackside cage traps are a frequent sight along the NW Circuit.

A final word:

The NW Circuit is well worth the physical demands it makes. But as one DOC publication states:

“The circuit is only suitable for well-equipped and experienced trampers who can handle the adverse weather conditions which are bound to be encountered on such a long trip”.

If you are looking for a more comfortable option then the 32 kilometre, three day Rakiura Great Walk, the so-called Rat Walk, will fit the bill as it provides a gentle introduction to the landscapes of Rakiura and can be walked year round.

Day 1: Monday: Halfmoon Bay to Port William Hut: 4 hrs.

After an unusually leisurely breakfast at our luxury Rakiura Retreat bolthole we tottered off mid-morning, out into intermittent light showers. The predicted rain hadn’t eventuated. The weather prognosis for Rakiura was unusually benign: only two days of showery weather were forecast.

The first day followed the Rakiura Great Walk track, a well constructed gravelled surface with all the accoutrements of side drains, wooden bridges, netted duckboards and… no mud. The like of which we wouldn’t see for another ten days. By and large the NW Circuit is world renowned for its mud… treacly stuff. Squelchy suck your boots off mud. Local trampers describe the mud on the NW circuit as: Ultra bog… sloppy, boggy and happy to admit your entire boot, ankle and calf. Here’s where leather boots and my knee-length Quagmire canvas gaiters were a boon.

As with many Great Walks the Rakiura walk is fitted out with an ‘Entrance Statement’ and accompanying information board. The arched entrance is a stylized anchor chain reminding visitors of the ‘links’ between Rakiura/ Stewart Island and Motu Pohue/ Bluff on the South Island.

Timbergetting at Maori Beach.

Our lunch stop, Maori Beach, was occupied by a massive NZ fur seal, sand-coated and in no mood to vacate its warm sunny spot. We tiptoed around the slumbering beast and headed for the nearby campground for lunch. Afterwards we checked out the remains of the old Maori Beach sawmill hidden in nearby coastal scrub. Sawmilling began in 1913 and at its peak Maori Beach sported a large wharf and network of tramways to extract the valuable Rimu or Red Pine. Rimu is a Podocarp with narrow prickly leaves which was sought after for its strength, density and straight grain. Brian recalled that his family home in Melbourne had been panelled with NZ Rimu. At the onset of The Great Depression the mill closed and with it the last of Rakiura’s sawmills.

Port William Hut.

By mid-afternoon we pulled into the Port William Hut, the largest of the NW Circuit’s huts. Port William started life as Williams Bay, named after a member of the Australian shipping and trading firm: Lord, Williams and Thompson. As is often the case in NZ’s summer tramping season, the inn was full. Two large bunk rooms occupied, mainly by a commercial tour group from Ruggedy Range Adventure Tours. A local Oban business, so that’s good to see. Other inhabitants included a couple from Denmark and two Yanks. One trying to wrangle a free night out of the hut wardens and the other grazing on a tucker bag full of breakfast crispies, seemingly her sole source of sustenance for the next three days.

Port William 1867.

But way back in 1876 things were quieter. The government, in an attempt to settle Stewart Island, opened up Port William as a ‘utopian settlement’, to be called Shetland. Fifty Scottish families were enticed over, no doubt seduced by offers of free land. But it was always a pretty grim place. It is thought that the Shetlanders lived in boat shelters dug into a bank, rocked and turfed over to make them waterproof. Only a few years later all that remained was a grove of Australian gum trees, still there today.

Day 2: Tuesday: Port William to Christmas Village Hut via Bungaree Hut: 10 hrs.

The spectre of the 10 hour walk ahead had us trackside by 7.15am and arriving at Bungaree Hut in good time… three and a half hours. My notes record the terrain as:

“undulating country in damp forest/muddy track/tree roots”.

Bungaree was occupied by a solitary backpacker confined to barracks by hooch-induced inertia and a plague of the notorious Kiwi biting midges (sandflies).

Christmas Village Hut.

After a short breather at Bungaree we faced up to the six hour walk to Christmas Village. This was really hard going: up and down, up and down. Muddy tracks, creek crossings and tree roots. The tedium relieved by a short two kilometre trot along the golden sands of Murray Beach. Lonely Planet recommends a swim here but cautions against a sunbathe because of the biting midges. About three kilometres from the beach is a hunters hut, the old Christmas Village Hut. By 5.00pm we were stuffed and thought Christmas Village Hut would never appear. But appear it did. Just on 6.00pm. An eleven hour day. No village of course but a 12 bunk hut built in 1986, unoccupied except for a largish solitary orange Glad bag.

The Glad bag contained a hefty Wilderness Equipment rucksack whose owner, Louise appeared soon after, having climbed Mt Anglem. Louise, we discovered, was a late riser, rarely vacating the premises before 10.00am. But a very fit lady undeterred by her 35 kilogram burden and a regular 6 to 7 hours on those dodgy Kiwi tracks.

Day 3: Wednesday: Mt Anglem or Hananui: 980m: 6 hrs: altitude gain 800m.

Another of Brian’s faux ‘rest days’. Sally sensibly applied the description literally and treated herself to a day off. The Mt Anglem track is atrocious: deep gullies flowing with water, muddy and root bound. And this was in fine weather. What it would be like in heavy rain is best left undescribed. After several hours we stood on the highest point of Rakiura. I don’t want to offend my Kiwi tramping friends, but let’s just say that the track was a Park Ranger’s worst nightmare. But all is forgiven, the summit gave expansive views over the whole of the northern part of the island and across Foveaux Strait to the South Island. As a bonus there below was a cirque basin and a small moraine dammed tarn.

Mt Anglem was named for Captain William Andrew Anglem, whaler and son of trader William Robert Anglem and his high born Maori wife Te Anau. The accuracy of Anglem’s 1846 Foveaux Strait sailing chart made a valuable contribution to Captain John Stokes’ survey of southern coastal waters in HMS Acheron. Stokes named the mountain in honour of William Andrew Anglem.

On our return to the hut the population of Christmas Village had exploded to now include three Kiwis and three French backpackers. Fran was a local Bluff woman who was solo walking the track with an out-sized and an unmanageably heavy rucksack bulging with a set of saucepans purloined from her kitchen back home in Bluff. Not quite in the same league, fitness wise, as Louise. But like most Kiwi trampers, Fran wasn’t about to throw in the towel. Yet.

Day 3: Thursday: Christmas Village Hut to Yankee Hut: 6 hrs.

Brilliant weather today. After a steep climb to start, a surprisingly dry track heads NW through Rimu forest for five kilometres before descending onto Lucky Beach. Lucky Beach was boulder strewn and with the tide and biting midges sweeping in we didn’t linger. From Lucky’s the track climbs steeply through the bush and then trends along the 100 metre contour; ‘undulating’ terrain for about 2 hours before descending steeply to Yankee River Hut.

Yankee River Hut

What a spot! A brilliant location at the mouth of Yankee River, though another bouldery beach. We stripped off, much to the delight of the midges, and cleaned up, washed our smelly clothes in the fresh water before finally being carried away by the midges. Yankee River was named for one Yankee Smith.

Rucksack and Fran drifted in eventually, just on dusk. She had decided to call off her walk. If I had been carrying her rucksack I’m pretty sure I would have abandoned ship several days earlier. One tough lady. Fortunately for Fran, Yankee River is one of the few locations on the NW Circuit with mobile phone reception. She contacted her husband at Bluff arranging for her extraction by boat early the next day. A sensible move on Fran’s part.

Day 4: Friday: Yankee Hut to Long Harry Hut: 5 hrs.

It was drizzling lightly as we exited the hut at 8.00am, minus rain gear as it was so humid. Another steep climb over Black Rock Point to the 200 metre contour to start the day.

Kiwis: the feathered variety.

It was here that that I spotted my first kiwi. One of my motivations for tackling the NW Circuit was the possibility of snatching a sighting of a kiwi. The kiwi or Tokoeka (I was told by a Kiwi tramper that it means a Weka with a walking stick), is New Zealand’s faunal symbol. This tubby flightless bird has defunct vestigial wings, feathers as soft as fur, is short-sighted and can sleep for up to 20 hours a day. There’s nothing else to do in NZ. My kiwi was a Stewart Island Brown kiwi (Apteryx australis lawryi), a much larger bird than I imagined. It wasn’t put off by my presence as it went about its business of hoovering up invertebrates using its long bill. Its diet also includes seeds, berries and even the occasional freshwater crayfish. By day they roost in burrows or undergrowth but the Stewart Island kiwis can sometimes be seen out foraging.

Habitat destruction and predation by stoats, ferrets, dogs and cats means that the kiwi is under threat over much of its NZ range; except for Rakiura where its population is estimated to be 20,000 and stable.

As we descended towards Long Harry Hut we glimpsed the first of many great vistas along a steeply cliffed coastline with lines of swell rolling in to crash against cliff and boulder beach. Over the next three days we would be treated to many such views. Our early afternoon arrival gave time for washing, beachcombing followed by a nana nap.

Long Harry Hut

Long Harry, a twelve bunker replaced in 2002, is perched on a headland overlooking the wild waters of the Foveaux Strait. It was named after Henry Woodman aka Long Harry, an early settler on Smoky Beach. After dark we watched the 12 second flash of Bluff Lighthouse across the Foveaux Strait to the north. The only other occupant for the night was Louise. Our guidebook said that Long Harry is the best spot to see penguins: Fiordland crested and Yellow-eyed Penguins. Not that we saw any after a desultory search along the beach.

Saturday: Day 5: Long Harry Hut to East Ruggedy Hut: 6 hrs

Up at 5.30am to heavy cloud cover and trackside by 7.30am leaving Louise still comatose in her bunk. Another day of brilliant views, the experience tempered by those 200 metre ascents. A top lookout, one of the few on the circuit that gave uninterrupted views westward across the Inner Passage to Rugged Islands with the appropriately named Ruggedy Range off to our south. The Ruggedy Range, a saw-toothed line of mountains, rises abruptly from the coastline to 500 metres. Below was East Ruggedy Beach and the extensive sandy estuary of the Ruggedy Stream. A welcome change from the boulder beaches thus far. A helicopter buzzed around looking for a likely drop-off zone. We found out later that two DOC officers had been dropped off to cut the track back to Long Harry. Long overdue in my opinion.

East Ruggedy Hut

East Ruggedy, also known as The Ritz, is eminently comfortable. It had a large verandah facing west to soak up the afternoon sun, ideal for drying our washing.

The Hunters

Just on dusk a hunter decked out in serious camo gear stalked in. A bloke all the way from Perth WA, here for a few weeks of hunting and currently holed up in a rock bivvy with a few mates on West Ruggedy Beach. Overnighting in a rock bivvy is a Kiwi speciality, something that all rugged Kiwi trampers and hunters have to do to earn their stripes.

Sunday: Day 6: East Ruggedy Hut to Hellfire Hut: 7 hrs.

Another early start in ideal walking conditions: cloudy cool. An easy walk through the scrub to West Ruggedy Beach and with the tide just right we scooted around the rock promontory which at high tide forces walkers to leave the beach and take to the inland route. The beach is one of the most scenic on the NW Circuit, framed by the jagged peaks of Ruggedy Range to the south and The Ruggedy Islands off-shore.

But the euphoria of beach cruising ended all too soon. At the end of the beach the track goes feral. A climb and sidle around Red Head Peak (510 m), and then another steep climb into Ruggedy Pass before dropping again to another Kiwi speciality, the boulder-strewn beach… Waituna Beach. From the beach we had good views of Whenua Hou, Codfish Island. The entire island is protected as Whenua Hou Nature Reserve. It is famous for its feral animal eradication program and as a breeding refuge for the threatened Stewart Island kakapo population.

The final section of the Hellfire day is another 200 metre climb up through the brush. A muddy tramp as the track sidles inexorably up the three kilometres to Hellfire Pass Hut. Seven and a half hours on the hop.

And here’s a surprise. Hellfire is set on a 200 metre high sand dune with outstanding views over Rakiura’s swampy interior, our destination two days hence. Hellfire is said to be named for the heavy seas which pound Little Hellfire Beach south of tonight’s hut.

Hellfire Hut

Our fellow inhabitants that night were a young Czech couple fruit picking their way around NZ. The next hutee to arrive was a gumbooted Kiwi, Danny. Although very quiet, Danny was a fount of information about Rakiura, Oban, the NW Circuit and NZ history. And last but not least, Louise drifted in, fashionably late in the dark but, as always, unperturbed.

Ambergris

Danny showed us a chunk of soft rock. This he explained was ambergris which he had found on a beach. The word ambergris comes from Old French or middle ages Old English, “Ambre Gris” or “Grey Amber”. Ambergris is a secretion of the gut of the sperm whale and can be found floating upon the sea, or lying on the coast. Because the beaks of squid have been found embedded within lumps of ambergris, scientists have theorized that the substance is produced by the whale’s gastrointestinal tract to ease the passage of hard, sharp objects that the whale might have eaten. The sperm whale usually vomits these, but if one travels further down the gut, it will be covered in ambergris.

Ambergris, much like musk, is known for its use in creating perfume and fragrance. Perfumes are still manufactured with ambergris. Ancient Egyptians burned ambergris as incense, while in modern Egypt ambergris is used for scenting cigarettes. During the Black Death in Europe, people believed that carrying a ball of ambergris could help prevent them from getting the plague. This was because the fragrance covered the smell of the air which was believed to be a cause of plague.

In the USA the possession and trading of ambergris is illegal, while in Australia its export and import is banned. New Zealand, home of the open marketeers, has, of course, a freewheeling attitude toward the collection and trading of ambergris. Possibly $NZ 15.00 a gram. A 1.1 kg piece of ambergris found on a beach in Wales UK was sold for £11,000 at an auction on 25 September 2015 to a French buyer.

Monday: Day 7: Hellfire Hut to Mason Bay Hut: 7 hrs.

Another coolish start with the inevitable climb, a 100 metres ascent onto a 300 metre ridgeline which provided excellent views over Little Hellfire Beach and in the distance, Mason Bay. Mason Beach materialized some five hours later and so did a startled and exceedingly plump Kiwi moggie. Right where we hunkered down out of the wind for our lunch break. Where’s the hunting fraternity when you need them?

Mason Beach.

Mason Beach is touted as,

“one of the most scenic on the island”.

Having read this sort of beat-up many times before I was initially sceptical. But it was truly a great ramble, especially with the ebbing tide exposing a wide, hard, sandy beach; easily a match for the great surf beaches of South-East Queensland minus the hordes of tourists. It is the largest of Rakiura’s beaches, a twelve kilometre sweep of sand extending from Mason Head in the north to Ernest Islands in the south. Mason Bay contains one of the most extensive inland dune systems in the Southern Hemisphere, with dunes extending inland for nearly three kilometres and reaching over 200 metres in height. This is one of New Zealand’s last untouched transgressive dune systems (also known as mobile or migratory dunes and sand drifts). It is backed by the Mason Bay Duneland, a dunefield of national conservation significance principally because of the presence of threatened plant species such as Austrofestuca littoralis, a sand tussock, and the rare creeping herb Gunnera hamiltonii.

For me it was an avian paradise, crawling with shore birds: pied cormorants, plump pacific gulls, herds of sooty oystercatchers, but no pied oystercatchers which usually can be found striding up and down sandy beaches in SE Queensland. But best of all was a sighting of a pair of Stewart Island shags, replete with their distinctive orange legs and feet.

Mason Bay Hut

After an hour on the beach our marker to turn inland appeared at the mouth of Duck Creek. No ducks, but a bevy of sun bathing backpackers braving a watery NZ sky and a sneaky little breeze. Mason Bay Hut (20 inmates) is at the junction of two main track systems – the Northwest Circuit and the Southern Circuit – both nationally and internationally important for their remote nature. But Mason Bay is becoming increasingly popular with slackers who access the area using the Freshwater water taxis and the Mason Bay-Freshwater track. Well–heeled tourists arrive by aircraft, landing on the beach and walk the few kilometres to the hut. The Mason Bay-Freshwater track is a difficult track to maintain as it is through a wetland. Encounters with other visitors are common, especially in the Duck Creek–Island Hill area. In the summer months overcrowding has been experienced at the Mason Bay tramping hut. This DOC hut was upgraded in November 2005 to mitigate some of these concerns.

In 2006 visitor monitoring was undertaken to help determine the future management of recreational opportunities in the Mason Bay area. One of the outcomes of this monitoring work was a limit on concessionaire use of the Mason Bay hut and the track system between Mason Bay and Freshwater. The walk from the ferry landing at Freshwater Landing hut to Mason Bay hut is only three hours, a tempting prospect for the summer flood of visitors, many of whom come to Mason Bay to see a Stewart Island brown kiwi in the wild. Just on dusk squads of braying visitors head off into the brush clutching torches all hoping to flush out a tame kiwi or two. Good luck with that one. Danny and Louise drifted in after dark.

Huts are sociable places in the main, but Mason Hut was one of my all time least favourites. It could generously be described as restless on the night of our stay. Overcrowded bunk rooms, young backpackers determined to party well into the wee hours of the morning and an odious loud yachtie and his daughter parking their bums on the kitchen preparation benches proved too much after the solitude of the huts thus far. It was one of those times when my one man Macpac tent would have been hiking heaven. Bring on tomorrow.

Tuesday: Day 8: Mason Bay Hut to Freshwater Landing Hut: 3 hrs

Up early and out to the kitchen for breakfast and to pack. I’m sure the overflow of hutees sleeping in the kitchen weren’t impressed with our crepuscular departure. It was all too much for Danny and he had already fled in the moonlight intending to walk the final 38 kilometres back to Oban.

Fifteen minutes eastwards along an old tractor track is the DOC office. This collection of re-purposed farm buildings was previously the old Island Hill homestead, a lowland sheep run operating from the 1880s. The two pastoral leases in the Mason Bay area were Kilbride and Island Hill, both established on the red tussock grassland and shrublands of the Freshwater River lowlands.

The Island Hill Run

The first run holder was William Walker (1879 to 1893) who ran up to 1600 sheep and worked hard on improvements like drainage ditches and fencing. The last holder was Tim Te Aika who held the run from 1966 to 1986. Tim survived by mixing farming with hunting and possum trapping. His wife Ngaire managed the family chores without electricity, home-schooled two children and had to order stores a couple of months in advance. The last of the sheep were removed in 1987 when DOC took over.

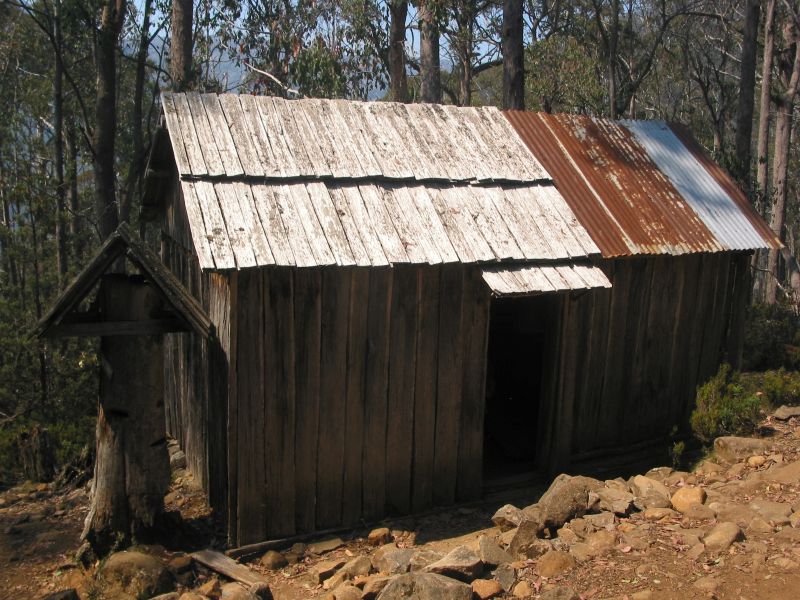

Making do on Island Hill Run

The logistics of viable sheep farming in this remote corner of the world were daunting. The shearing shed, built in 1953, was made from scavenged beach timbers, mostly dunnage. That is, planks used to hold a ship’s cargo in place. Fencing was virtually non-existent. Sheep roamed free over the grasslands until mustering time. Then improvised fencing of old fish nets and cut brush were used to hold the sheep. At shearing time in summer up to 1600 sheep were shorn by four shearers. By 1966 the hand shears had been replaced by electric shears powered by the tractor and later by an 8 KW generator. No such electric luxury for Ngaire in the homestead.

After the shearing the wool clip had to be transported to Bluff or Invercargill. This was the really hard part of the sheep grazing industry on Rakiura. Early on, the wool was carted to Freshwater Inlet where it was stored in sheds waiting for favourable weather to get it across Paterson Inlet to Oban on Halfmoon Bay. Tim Aika, ever the innovator, tried using a small plane which landed first on the beach and later on a 600 metre airstrip cut into the tussock grassland. Tim’s son-in-law flew the wool packs out returning with bags of superphosphate.

Today was our easiest walk thus far: a mere three hours and fifteen kilometres over the flat swampy terrain of the Freshwater River valley. At 75 sq km Freshwater is the most extensive lowland on Rakiura, occupying a faulted depression which dips gently to the east. Freshwater’s headwaters lie in the Ruggedy Ranges and it flows SW for 25 kilometres across wetlands of peat bogs, ponds, sand ridges, shrubland and tussock grasslands. It formed about 14,000 years ago, after the last ice age. Water flooded Foveaux Strait and Patersons Inlet and created the Freshwater wetland. The track follows the line of an old 16 kilometre government road and drainage system built in the 1930s to link Freshwater Landing with Mason Bay. Deep drains were dug and the spoil thrown up and used for the carriageway embankment. This was topped off with piles of Manuka to make a corduroy road.

We landed at Freshwater Hut in time for midday lunch and time enough for another of Brian’s infernal peak bagging escapades. Freshwater is the site of a swing bridge across the Freshwater River and a landing for the water taxis. It is a pokey little hut with a bunk room, kitchen benches and a table. A tight squeeze for its thirteen overnight inhabitants. But much better than beating off the midges.

Rocky Mountain

After lunch Brian and I took off on the one and a half hour climb to the alpine summit of Rocky Mountain at 549 metres. From here we had magnificent views back along the spine of our walk over the past few days: Ruggedy Mountains, Hellfire Pass and Mason Bay. To our north, about twelve kilometres hence, rose Mt Anglem, the highest point on Rakiura. Off to the south east were the waterways of Patersons Inlet and Whaka a Te Wera and the largest island, Ulva Island. We visited Ulva after we completed the NW Circuit.

Ulva Island: Te Wharawhara.

Ulva Island is yet another NZ conservation success story. After rats were eliminated by 1996 it was designated as an ‘open sanctuary’, or as DOC describes it, “a zoo without bars”. Here the bird life is now as prolific as it must have been in the primeval New Zealand forest. Expect to see Stewart Island wekas (flightless) and a number of re-introduced birds: South Island saddleback, Stewart Island robin, the Rifleman, Tui, Stewart Island brown kiwi, New Zealand wood pigeon and Yellowhead. This is far from a complete bird list and competent birdwatchers would be very pleased with their time in this avian paradise.

Wednesday: Day 9: Freshwater Landing Hut to North Arm Hut: 8 hrs:

The young backpackers cleared out in the dark, hoping to do the 12 hour walk to Oban in order to catch the 6pm ferry. We left at first light, just on 7.00 am. It was another cloudy morning with the potential for showers or rain. This section of the NW Circuit has a well deserved reputation for being steep and slippery as it passes over Thompson Ridge to the North Arm of Paterson Inlet. Creeks in this section can become impassable after heavy rain, so we didn’t dawdle.

This was a hard day: steep climbs, mud, roots. The track was in atrocious condition. Brian tripped near the top of Thompsons Ridge and required first aid to stem the bleeding. But there was no option but to soldier on. A long tricky descent followed which eventually emerged at Patersons Inlet. But our pain wasn’t over yet. The track then contours around the inlet for several kilometres before releasing exhausted walkers at the picturesque North Arm Hut.

North Arm Hut

North Arm Hut is one of the three swanky huts built for the Rakiura Great Walk and as such it costs extra to stay there. This is a newish 24 bunk hut with a large open kitchen and dining area overlooking Patersons Inlet. The hut was full on our night there but one certainly couldn’t whinge about the other inmates. These were older walkers: international backpackers tend to avoid the hut as it costs a few dollars more than standard huts.

Thursday: Day 10: North Arm Hut to Oban: 5 hrs.

Departed in cloudy threatening conditions. Nothing unusual about that but with only 12 kilometres left we weren’t concerned about getting our tails wet. The Great Walks standard track made for quick and easy walking. By midday we were on the outskirts of Oban making a beeline for the pleasures of the South Sea Hotel. Our challenging 125 kilometre adventure was over, celebrated by a schooner of Montheith’s dark ale and a Works Burger. Thanks to my cheerful walking companions Brian and Sally. and to Brian for leading and organising the walk.

South Seas Hotel