My bushwalking friend Brian is nothing if not persistent. And so it was that we were off again to walk the length of The Kerries Ridge, said to be ‘some of the finest walking in Kosciusko National Park.’ He for a third attempt and me for a second. Our previous encounters had taught us that The Kerries ridge was not a good place to be in bad weather.

by Glenn Burns

This time we were accompanied by a surprisingly favourable weather report and that trio of venerable track dogs: Richard, Joe and his walking mate from Townsville, Noel . As an added inducement Brian had suggested that we should check out The Brindle Bull.

My initial thoughts on The Brindle Bull turned to one of Brian’s après-walk high country watering holes: a schooner of cold Kosciuszko Pale Ale or perhaps a Razorback Red Ale….. Who could resist?

Later, far too late, while poring over some Kosciuszko maps on the flight down, I discovered that The Brindle Bull was, in fact, a 1890 m peak in The Pilot wilderness. Just another peak on Brian’s interminable 1000 m ‘to do’ list.

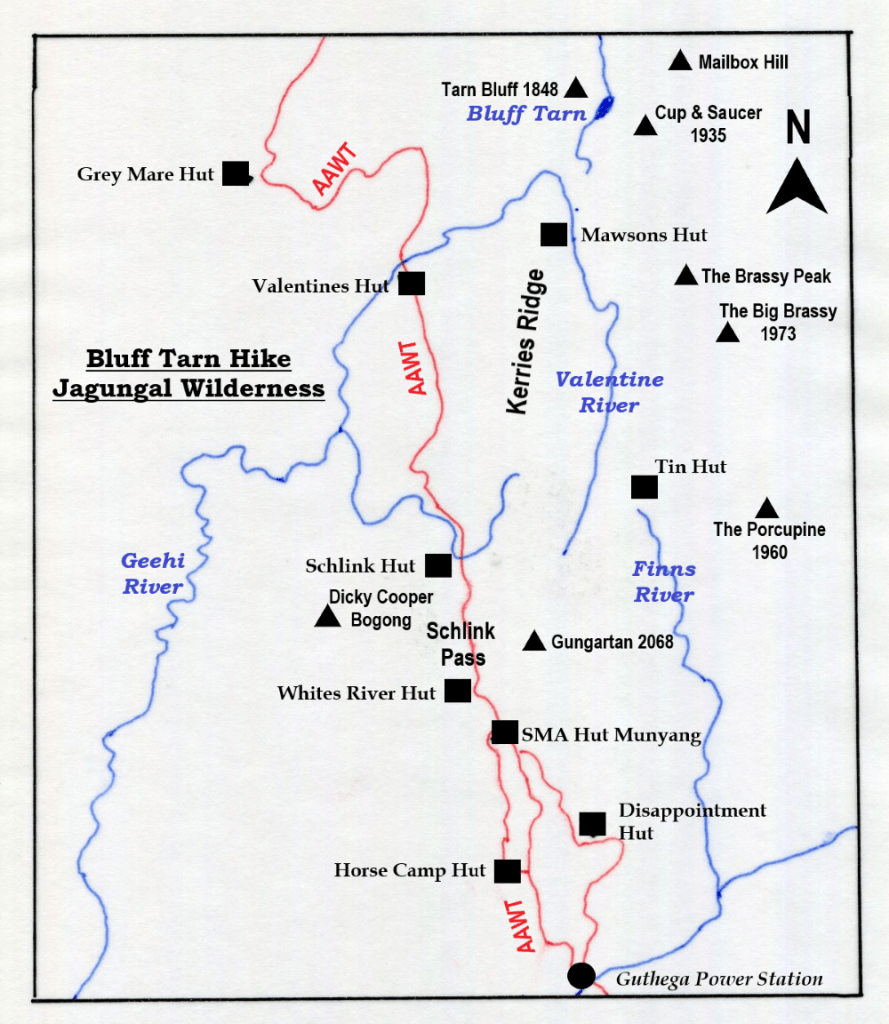

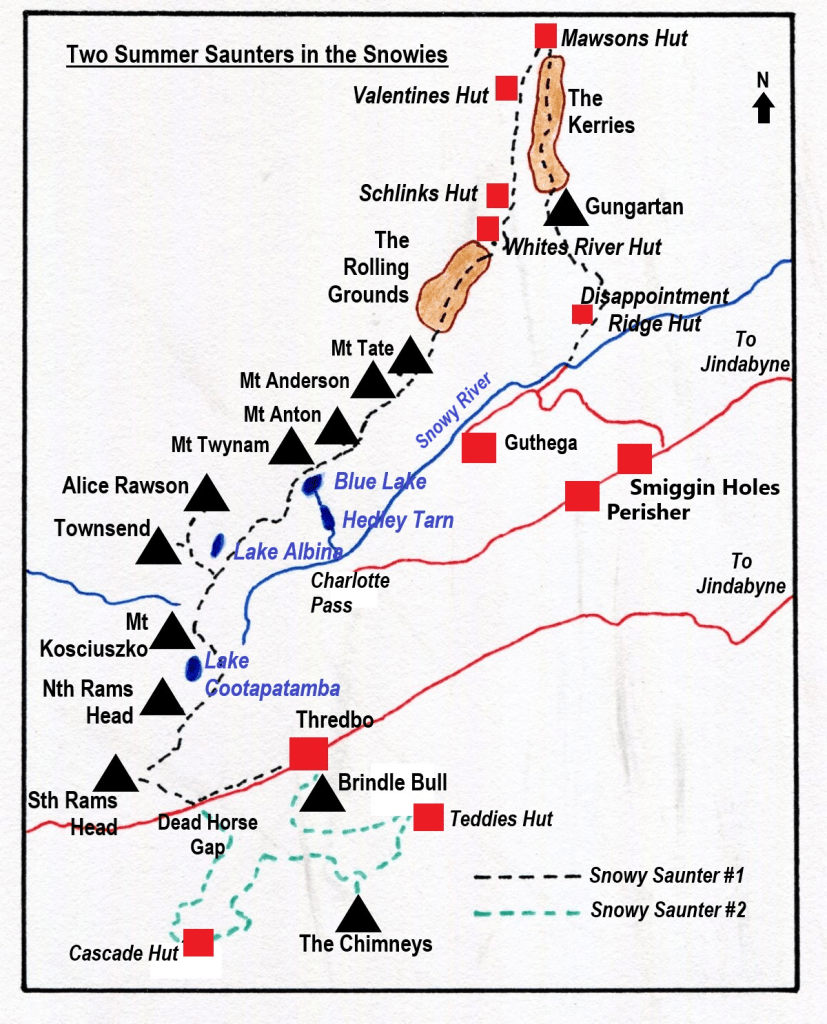

Our initial 90 kilometre circuit, big chunks of it off-track, was a grand tour of some of Australia’s highest peaks and ridges: Disappointment Ridge, Gungartan, The Kerries, The Rolling Grounds, Mt Tate, Mt Anderson, Mt Anton, Mt Twynam, Mt Carruthers, Mt Lee, Mt Townsend, Alice Rawson, The Rams Head, South Rams Head and at 2228 m, the biggest bogong of all, Mt Kosciuszko.

The final four days would follow The Main Range, also called the Snowy Mountains, over 2000 m, well above the tree line. In fine weather this is one of Australia’s premier walks, but it is very exposed and the weather highly changeable. Storms and even sleet are not unusual in February so walkers need to be well prepared.

Map of Hike to Kerries, Rolling Grounds and Main Range

Sunday: Munyang (Guthega) Power Station to Disappointment Ridge: 8 kms

Our people mover piloted by sons Alex and Ian discharged its cargo of old fellows at Munyang (Guthega) Power Station (1300m) soon after 9.00 am.

Munyang (Guthega) Hydro Power Station

MUNYANG (Guthega) hydro power station is the start of many of my favourite walks in Kosciuszko.

Munyang was also the start of the construction of the first major project of the Snowy Scheme in 1951. The Guthega project was awarded to a Norwegian firm Ingenior F. Selmer. A serious player in global dam and hydro construction.

Selmer were required to construct a dam (Guthega Pondage) 30 metres high and 107 metres long; a 5 km tunnel with a penstock pipeline and power station producing 60,000 Kw, the smallest output of the Snowy power stations.

The bulk of the workers were Norwegians (450, mainly labourers) from the rural areas of the Arctic Circle.

On the 21 February 1955 , only a few weeks behind schedule, electricity flowed from Munyang. Like my fellow bushwalkers the Snowy Scheme had sprung to life.

The word Munyang or Muniong derives from the First Nations people. When camped on the Eucumbene Valley, they would point to the snow covered Main Range and repeat the word ‘Munyang’ or ‘ Muniong’ . Said to mean ‘big’ or’ high mountain’. Also’ big white mountain’.

What followed was a salutatory introduction to alpine walking: hauling our backpacks, bulging with tucker for seven days and piles of warm clothing, four kilometres uphill on the Disappointment Spur fire trail to Disappointment Hut (1640 m).

Disappointment is spiffy little four berther ex-Snowy Mountains Authority Hut set in a grove of snow gums and had been spruced up with a lick of green paint. Built as a survey hut in the 1950’s by the Snowy Mountains Authority, it is of weatherboard and iron roof construction with wooden floor. Cosy as.

Disappointment Spur is said to have been named by a group of stockmen travelling from alpine meadows near Gungartan through to Jindabyne. They followed the ridge down only to be ‘disappointed” at not being able to cross a raging Snowy River. Or so the story goes.

Any thoughts I had of settling in for a comfy overnighter in the hut were quickly scotched by our over-eager leader, ever anxious to press on. But not before tucking into a hearty al fresco lunch prepared by Joe and Noel: fresh Thredbo Bakery bread rolls packed with generous slabs of Jarlsberg cheese and slices of salami. A decent lunch time feed for a change.

The afternoon’s off-track climb onto Disappointment Spur was a fair bugger, pushing uphill through whip-stick thickets of scrubby re-growth from the 2003 fires. At 3.30 pm we hove to. Thank god Eager Beaver wasn’t at all keen on the extra three kilometres over Gungartan to Gungartan Pass.

The make-do campsite at 1940 m on the picturesque alpine herbfields of Disappointment Ridge was no hardship. Tickety-boo, in fact: springy snow grass bedding, speccy views north to Gungartan and Jagungal, nodding pastures of yellow billy buttons, silver snow daisies, Australian bluebells and white gentians all topped off by the promise of fine weather for our passage across The Kerries on the morrow.

Monday: Gungartan, The Kerries to Mawsons Hut: 9 kms.

Despite Brian’s daily assurances that there was ‘no hurry’ to pack up each morning, soon after 5.15am we heard the familiar zzzzzzzzip from his green hutch and Brian would, wombat like, reverse out on all fours into the crisp, crepuscular dawn. Air temperature hovering at barely 1°C according to my pack thermometer. A quick breakfast of weet-bix, muesli or maybe hot porridge, washed down with a mug of piping hot coffee or tea. Our departure was invariably before 8.00 am. No hurry. No pressure.

First up, Gungartan, a jumble of granitic tors and a trig station which had seen better days. At 2068 m this is the highest point north of the Main Range. Stretching away to its north was the open rolling ridge of The Kerries (2040 m). A magnificent walk across trackless wildflower meadows dotted with granite boulders, alpine bogs and mountain streams.

As with much of the Kosciuszko plateau, the Kerries Ridge has been eroded to form a small peneplain. It’s surface is capped by granitic ( granodiorite) boulders rising only a 50 to 100 metres above the general landscape. Like much of the Main Range , the underlying rock is Silurian Mowambah Granodiorite, some 430 to 400 million years old. Granodiorite, superficially similiar to granite, is also a coarse grained intrusive igneous rock. But, there are important differences in mineral composition. I generally differentiate from granite by the greater abundance of dark minerals in granodiorite.

But this seemingly benign landscape can change dramatically in bad weather and walkers need to be competent off-track navigators to find the safety of Mawsons, Schlinks or Tin Hut in a whiteout. No such problems today: perfect weather, duelling GPSs, a twin-set of maps, a cart load of compasses and the lads keeping two wayward old-school navigators on a tight reign. Although the mushrooming cumulo-nimbus clouds suggested wet bums if we mooched around too long enjoying our sojourn on The Kerries.

Mawsons Hut

The three-roomed Mawson’s Hut (1800 m) was built in five days in 1929 by Herb Mawson, manager of Bobundra Station. Not Sir Douglas Mawson, Antarctic hero, as generally supposed. It is typical of cattlemen’s summer huts built all over alpine and sub-alpine Australia: corrugated iron walls, corrugated iron roof, wooden floors and a granite fireplace.

Generally dark, dirty and dingy but a welcome refuge when the weather turns bad. As it did. Fortunately we were snugly ensconced in Mawsons with our NPWS issue ‘Ultimate 500’ cast iron stove blasting out mega BTUs of hot air once Brian and cub stove technician Joe nutted out its many irritating idiosyncrasies.

As the rain eased, ‘Ken from Canberra,’ docked at Mawsons. A bespectacled public service mandarin type; pleasant, intelligent company and a mine of local bushwalking information.

Apparently Ken was road testing his born again status as light-weighter. A three day shake-down cruise to Mawsons Hut and The Kerries thence to Tin Hut on the Brassy Mountains with brand new Golite pack and pup tent of some new fangle dangle wafer-thin nylon stuff.

Ken joined us inside for an evening of tall story telling by those travelling troubadours, Joe and Noel… wild and woolly tales from Far North Queensland . Of the ‘now I know you don’t believe me but it really is true’ genre, and populated with characters with names like Gorilla Biscuit, Half a Cowboy, Pedal Pete, PVK…

Tuesday: Mawsons Hut to Whites River Hut via Valentine Hut. 13 kms.

An easy day starting with some minor off-tracking from Mawsons to Valentines Hut.

Valentines Hut

Valentines Hut has to be my all time favourite hut. A small weatherboard ex-SMAer, coated in cherry red paint and decorated with a frieze of six valentine hearts. Hence the name Valentines Hut. Cute. Maintained by the Squirrel Ski Club, it is always kept clean inside and out.

After a brief pit stop at Valentines, the rest of the morning was spent in a pleasant ramble through a tunnel of snow gums along the Valentine fire trail before finally popping out onto the Schlink trail, just in time to flag down the passing Snowy Hydro 4WD. No luck hitch-hiking here.

Meanwhile, still on the hoof, The Schlink ‘Hilton’ appeared for us soon after midday. None too soon as it was warm, windy and the high country horse flies were driving us batty. We ducked inside this fly-free nirvana for lunch.

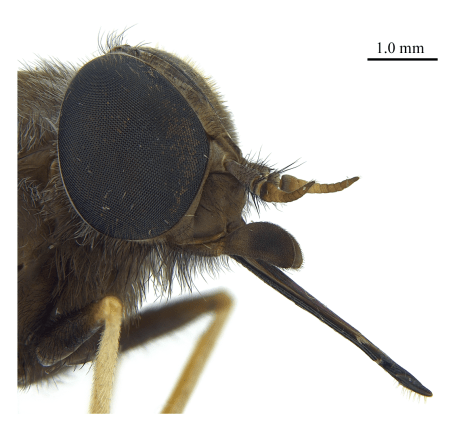

March, Horse or Vampire Flies

No horse flies, nor their sneaky little bush-fly buddies, nor any of those Lilliputian black ants that swarmed over us whenever we propped on tussocks of snow grass or rocks for a break. Horse or March flies are known by southern bushwalkers as Vampire flies. For good reasons. These bug-eyed pests lurk in piles of wet wombat and brumby poo waiting to pounce on any bushwalker foolish enough to be out and about without a full suit of body armour.

It also behooves me to inform the reader that it is the female who bites and draws blood. She lands on a likely victim, unfurls her proboscis and silently inserts it through multiple layers of clothing, canvas gaiters or even nylon rain pants to suck out your vital juices.

Meanwhile the real heroes of this story, the male horse flies, quietly go about their business, productively spending their days zooming from flower to flower, hoovering up nectar for a feed and pollinating those pretty alpine wildflowers as a sideline.

The Schlink Hilton was named after Dr Bertie H. Schlink who, in 1927, was the first to complete the 150 kilometre Kiandra to Kosciuszko ski run. Built in 1960, it is another ex-SMA hut, a massive 11 roomer maintained by The Gourmet Walkers Club. Sign me up.

Whites River Hut

And so onto Whites River Hut, which was burnt down by some dumb-cluck skier in winter 2010. The original hut was built as summer grazing hut in 1935 by Bill Napthali and Fred Clarke. It has been rebuilt in the mountain hut heritage style and the Kelvinator, a white annex, has been removed.

Whites River is now the official summer residence of Bubbles and Bubbles Jnr, bush rats extraordinaire. The mayhem and pandemonium caused by our two furry friends is well known to anyone who has ever checked out the hut log book or tried to snatch forty winks at Whites River.

As with our previous visits we spent much of the our evening ‘Bubbles’-proofing our gear; all rucksacks and food bags were then suspended on the nails belted into the huge transverse hut beams. Which seemed effective as there were no nocturnal disturbances from the Bubbles outfit but plenty from my hut mates who seemed to spend their night streaming outside to gaze at the brilliant star show, or so they would have you believe.

Wednesday: Whites River to Pound Ck via Mt Tate: 11 kms.

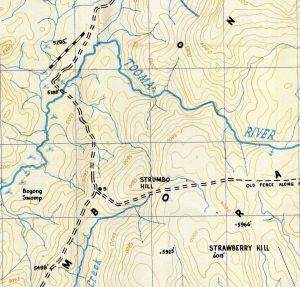

Today would be our hardest day, a distance of only eleven kilometres and a vertical ascent of 328 m… give or take a few major ups and downs. But the most problematic part was our traverse over the Rolling Grounds, which are described in one guidebook thus: ‘Known as the Rolling Grounds…. on a fine sunny day it is best described as bleak. What it is like in a blizzard is left to the imagination. The Rolling Grounds are notorious for difficult navigation in bad weather’.

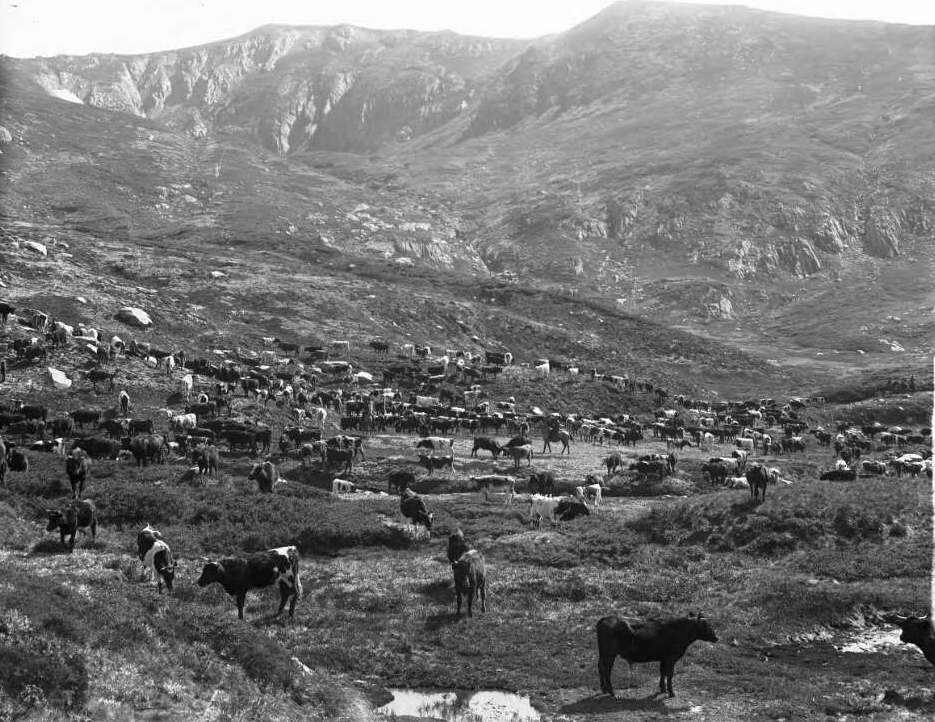

Fortunately the day was fine and clear, ideal conditions for crossing these high level alpine meadows and bogs. Just absolutely brilliant walking. It is said that The Rolling Grounds are so called because in the days of cattle grazing, stock horses would make their way up to roll in the numerous depressions between clumps of snow grass.

By 10.30 am we reluctantly vacated The Rolling Grounds and dropped into Consett Stephen Pass to begin the tedious haul up to Mt Tate, 2028 m and the start of the Main Range.

The lads were in seventh heaven, an orgy of peak bagging for the next four days.

Walking the Main Range

The Main Range. We were now in the Alpine Zone, well above the tree line, travelling at an average elevation of 2000 metres. Here are Australia’s highest peaks: Tate (2068 m), Carruthers (2145 m), Alice Rawson (2160 m), Ram’s Head (2188 m), Twynam (2196 m), Townsend (2210 m) and Kosciuszko at 2228 m. The Main Range is predominately granitic, an intrusive rock formed deep within the earth’s crust by the slow cooling of molten magma. The overlying rocks have been eroded away through eons of time. But a belt of older belt of Lower Ordovician sedimentaries sneakily outcrops for parts of the Main Range walk. Much of the granitic bedrock along the Main Range has been subjected to great stresses and thus has a layered appearance, and is called gneissic granite.

These highest of our mountain peaks are typically rounded humps, bearing little resemblance to the typical pyramidal alpine peaks of Europe or the Himalayas. It is possible that this rounding took place in an early stage of the Pleistocene when a large ice cap covered much of the Main Range, extending as far south as Mt Bogong.

Later glaciation was valley glaciation. Temperatures now average 10C in summer and -5C in winter, too low for tree growth and most plants require special adaptations to survive. We needed four more days of fine weather to traverse the Main Range back to Thredbo.

Mt Tate was named after Ralph Tate, Professor of Geology at the University of Adelaide. From Tate’s trig summit we looked down to Guthega Pondage near where we had started three days ago and across the valley to the confrontingly named The Paralyser and The Perisher.

Onwards to Mt Anderson (1997 m) and below its southern flanks our overnight campsite in the headwaters of Pound Creek. This campsite was bereft of any cover, sunny and exposed, but we made ourselves comfortable on the snow grass and tumbled into our tents before 8.00 pm. Knackered.

Thursday: Pound Creek to Wilkinson Valley: 12 kms.

Brian’s original plan had been to walk through to Alice Rawson (2160 m), camping high up on the saddle between Alice Rawson and Mt Townsend. But such is the nature of high country walking that the prudent leader always has a contingency plan. For much of our trip we had been plagued by 20-30 kmh winds that showed no sign of abating. In fact, they were about to get a lot worse. So with the nor’westerlies idling along at 40 km/h and maximum gusts hitting 61 kmh it was decided that camping in the relative shelter of Wilkinson Valley under Mt Kosciuszko was our best option.

Despite the wind it was still an outstanding alpine walk along Australia’s highest points: Mt Anton (2010 m), the long crawl up Mt Twynam (2196 m), down onto the Main Range tourist track, back up to Mt Carruthers (2145 m) summit where we didn’t linger longer.

Instead we hunkered down for lunch behind a shelf of rocks overlooking Club Lake, one of the many moraine-dammed glacial lakes in Kosciuszko.

During the Pleistocene, small mountain glaciers ground their way down the valleys now occupied by glacial lakes. In recent historical times, during summer, huge flocks of sheep and later herds of cattle grazed these steep alpine slopes, fouling the pristine snow fed lakes below: Club Lake, Lake Albina, Hedley Tarn, Blue Lake and Lake Cootapatamba. Fortunately, the sheep and cattle were shown the door in 1963.

Mt Carruthers named after Sir Joseph Carruthers, a Premier of NSW, who instigated the construction of the Kosciuszko Road and the old Kosciuszko Hotel.

Between Mt Carruthers and Mt Lee the track dips onto a sharp exposed ridge formed when valley glaciers cut back towards each other (a col). This is windswept Feldmark, location of the rarest alpine plant community. Plants here must survive on a wind blasted ridge where the soil has been blown away, leaving only cold rocky ground. A fortuitously located info plaque allowed us to identify Alpine Sunray (Leucochrysum albicans spp alpinium), Coral Heath (Epacris gunnii), Feldmark Grass (Rytidosperma pumilum) and Feldmark Eyebright (Euphrasia collina spp lapidosa) and Feldmark cushion-plant (Colobanthus pulvinatus).

Far below was the basin of Club Lake, a moraine dammed glacial lake, the water held behind unsorted glacial debris. The track mercifully by-passed Mt Lee (2019 m) and skirted along the flanks of Mt Northcote (2131 m) and then descended into Mueller’s Pass. Descending further, we came to rest in the boulder strewn but picturesque Wilkinson’s Valley.

During the evening a pussy storm cell swept past accompanied by the roll of distant thunder, light rain and a lightning display of sorts. Which is just as well as I wouldn’t like to get caught out on this open valley in a bad electrical storm. But it was enough to confine the lads to their tents for half an hour before a dose of tent fever broke out and they poured out to watch the last vestiges of sunlight fade over the Abbott Range.

A blood red sunset from smoke haze drifting from the Victorian bushfires just 80 kilometres to our south west.

Friday: The Main Range and The Rams Head Range: 9 kms.

With the tents left up to dry, Brian herded his two-legged flock up Mt Townsend (2209 m) and Alice Rawson (2160 m) as a sort of a warm-up for what was to come later in the day. Minus our packs it was too easy, a brisk 45 minute trot to Townsend summit and then a pop over to Alice Rawson which had the more interesting views: down into Lake Albina and into the very precipitous western fall of Lady Northcote Canyon.

We stood on Mt Kosciuszko( 2228 m) by midday. Sharing the summit was the usual crew of day walkers, grey nomads, young international backpackers and five debonair track dogs who, with a certain degree of satisfaction and nonchalance, would point out to any unsuspecting tourist type who would listen, the mighty Gungartan, where we had stood five days prior.

Tadeusz Kosciuszko

Mt Kosciuszko was named by the Polish explorer Count Paul Edmund de Strzelecki who spent four years travelling in Australia. In February 1840 Strzelecki climbed to the highest point of the Snowy Mountains and decided to name it after his fellow Pole, General Tadeusz Kosciuszko, who had distinguished himself in the American War of Independence and had led an uprising in 1794 against Prussian and Russian control of Poland.

Strzelecki gave two reasons for using the name ‘Kosciuszko’. Strzelecki pointed out that in Australia he was “amongst a free people, who appreciate freedom” hence the name of the Polish liberation fighter was an appropriate choice. Another reason he gave was that the profile of Mt Kosciuszko resembled the memorial mound that honours Kosciuszko on the outskirts of Krakow. An interesting side line to this story is that Kosciuszko authorised the sale of all his Ohio (U.S.A.) property to buy freedom for slaves and provide them with an education.

Should you wish to read more about Tadeusz Kosciuszko, you could do no better than to have a gander at Anthony Sharwood’s tome: Kosciuszko, the Incredible Life of the Man behind the Mountain.

Then it was a dodder down to Rawsons Pass for lunch, hopefully sheltered from the near gale force 50 kmh wind gusts. After lunch we headed up onto the Rams Head Range but the boys were, strangely, more interested in finding a sheltered campsite than climbing North Rams Head.

The wind was now whipping across the open alpine meadows. Come 3.30 pm we called it off for the day and guyed our wildly flapping tents down behind a jumble of granite boulders. Evening showers drifted over, chasing us into our tents to cook our dinners only to re-emerge later to watch yet another red sunset.

Saturday: Rams Head Range to Thredbo. 10 kms.

Our last day on the track. We woke to a sky laced with thin wispy cirrus cloud, the harbinger of rain predicted for Sunday. Our route would take us over The Rams Head (2188 m) and South Rams Head (1931 m), descend to through snow gum woodland to Dead Horse Gap and follow the Thredbo River back to Thredbo.

As we approached South Rams Head a shaggy black swamp wallaby bounded past, closely pursued by a salivating dingo, closing fast. But this was one wily wallaby. On spotting us it saw its chance, performed a nifty u-turn, and headed back towards our group, placing us between it and the dingo. My last sighting was the swampy disappearing up into the pile of granite boulders behind us.

From South Rams Head trig we saw The Pilot Wilderness stretching off to the distant south: the Thredbo River Valley, Cascade Trail, The Pilot, Little Pilot, The Chimneys, Paddy Rushes Bogong and the Brindle Bull, masquerading as a mountain. These were some of the landmarks that we would visit after a rest day in Thredbo, but more of that some other time.

Meanwhile, a flock of Australian Ravens cawed overhead. These fellows were chasing the Bogong Moths that hibernate in vast numbers during summer in rocky crevices on our alpine peaks.

A final bush bash led down to Dead Horse Gap (1582 m). So named because a herd of brumbies perished there when trapped in a blizzard.

Then came a four kilometre dash down the Thredbo River trail, arriving at Thredbo just ahead of the first light sprinkles of rain. The first part of our summer Snowy Mountains adventure was over. It seemed to me that I had well and truly earned that schooner of Razorback Red. Which way to the Brindle Bull, Brian?