And so to the Brindle Bull. You may have read my previous account of our seven day saunter #1 along Kosciuszko’s highest peaks and ridgelines on The Kerries, Rolling Grounds and The Main Range. Our follow-up foray was into The Pilot Wilderness, south of Thredbo.

by Glenn Burns

But first, as it was Sunday, a day of rest, we parked ourselves in Thredbo. Along with hundreds of mountain bikers competing in the National Downhill Championships.

By Monday morning the drizzle eased, the BOM forecast was propitious so we set out again. This time on a shorter, forty kilometre circuit, at slightly lower altitudes but still over spectacular alpine terrain.

Our circuit started at Thredbo. Thence to Dead Horse Gap, the Cascade Trail, Bobs Ridge, Cascade Hut, the Big Boggy, Teddys Hut, The Chimneys, arriving back at Thredbo via the Brindle Bull Hill. A place name that Brian, our leader, seemed particularly smitten with and was determined to check out. My other companions on the Brindle Bull trip were Richard, Joe and Noel.

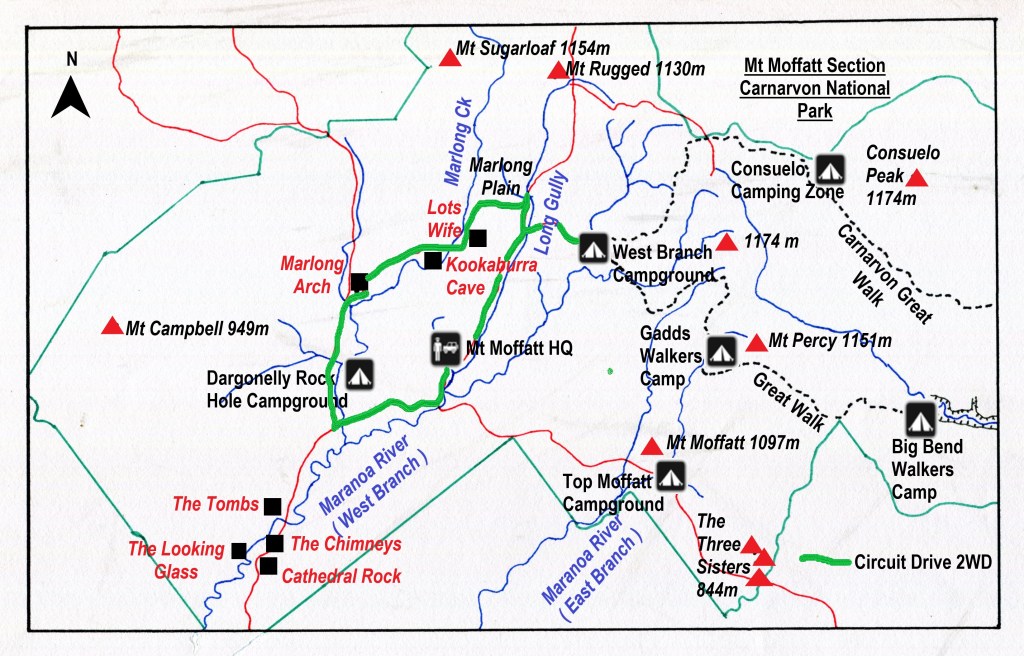

Map: Chimneys Ridge: 1:25,000. Geoscience Australia.

Map of Hike to Cascade Hut, Big Boggy, Teddys Hut, The Chimneys and the Brindle Bull

Monday : Thredbo to Cascade Hut: 12 kms.

With the mist lifting, Richard loped off, at a disconcertingly eager pace after our lethargic day of rest. The morning’s walk took us up the four kilometre Thredbo River tourist track to Dead Horse Gap, the trail head for the Cascade Trail. From here we would climb the Cascade Trail to the crest of Bob’s Ridge (1800 metres), a major south-west spur of the Great Dividing Range.

It is said that Dead Horse Gap takes its name from a herd of twenty or so unfortunate brumbies caught out in a blizzard. But today, the gap was merely a tame car park with an info board telling me that this was once the site of the Dead Horse Gap Hut, a summer grazing hut, built in 1932 by the Nankervis family of Tom Groggin Station.

This type of shelter hut, one of nearly 230 built in the Kosciuszko area, was an integral part of the transhumance practice of herding cattle and sheep up to the high summer pastures or snow leases as they were called. Other huts were built by miners and the Snowy Mountains Authority. But, as with many high country shelters, Dead Horse was lost to fire.

From Dead Horse Gap we engaged granny-gear for the five and a half kilometre drag up to the crest of Bobs Ridge at 1800 metres. Some 300 metres of altitude gain. The Murray River system to our right, the Thredbo- Snowy River to our left.

Here we settled into one of those outstanding lunch spots that leaders rave about, but rarely provide.

The lads loafed under the shade of gnarly old snow gums. Their bottoms comfortably settled on snow gum branches or sprawled out on the ground, padded by springy tuffs of snow grass. Best of all, none of those swarms of mini black alpine ants, the bane, one of several, of bushwalking in the high country.

The Brumby Saga

But these alpine woodlands are swarming with something on a grander scale… wild horses, brumbies, feral horses. Choose your side in the culture wars over brumbies in Australia’s high country.

We discovered a set of portable stockyards behind our lunch site and our progress up Bobs Ridge had been marked by pyramids of horse poo of such grandeur they would do pharaoh Rameses II proud.

We were, of course, in the setting for Elyne Mitchell’s much loved Silver Brumby stories. The presence of brumbies in Australia’s national parks is a divisive issue.

In other states they have been culled without much of a hue and cry from horse lovers. But in the high country of New South Wales and Victoria, a different mentality prevails. Here brumbies are cultural icons, Man from the Snowy River stuff.

Notwithstanding the damage wild horses do to alpine ecosystems, in parts of Kosciuszko National Park they seem free to roam pretty much unfettered. Their hooves trashing delicate alpine bogs and watercourses. As well, the brumbies selectively chomp out the tastier plant morsels.

No one likes to see horses killed, but the sad reality is that rehoming is not reducing the numbers of horses in Kosciuszko National Park fast enough to reduce population growth.

In 2023 the Australian Government’s Threatened Species Scientific Committee warned that feral horses could be a crucial factor in the final extinction of six critically endangered animals and two critically endangered plants.

Culling of feral horses started again in October 2023, with over 5,539 killed by aerial shooting. Another 427 were removed by trapping, rehoming and ground shooting. This is the first time that more horses were removed than their annual population growth.

Their days appear to be numbered. Under NSW legislation, the government must reduce the number of feral horses in Kosciuszko to 3000 by 2027. Still too many.

The best summary of the brumby issue that I have read is Anthony Sharwood’s The Brumby Wars (2021, Hachette). This is a book about Australia’s brumbies and the intense culture wars that have erupted about their removal from Kosciuszko National Park. Highly recommended.

From Bob’s Ridge we descended into the open Cascade Valley, currently hosting five brumbies chowing on their favourite alpine herbs and grasses. Clearly unfazed by the five plodders wandering past.

These open grassy alpine valleys are below the tree line at 1800 metres and you would expect them to be covered by snow gum woodland. Instead they are devoid of trees. A response to dense, freezing air rolling off the high tops and pooling in the lowest points of intervening valleys. Even snow gum seedlings cannot survive in these frost-hollows with their extreme swings of diurnal temperatures.

Cascade Hut

Cascade Hut, on the slopes of a ridge, is nestled in a grove of snow gums It is an old friend, a bushwalker’s and skier’s home away from home. The Nankervis family owned the snow lease at Cascades and had the hut built in 1935 with horizontal slabs and a bark roof.

The bark was later replaced by a corrugated iron roof. On one of our visits a reno job of a sheet of wildly flapping clear polycarbonate sheeting did nothing for its heritage value. This has since been rectified. The old hitching rail still stands, but these days serves only to prop up ever increasing numbers of mountain bikes.

Inside is a stone fireplace, dri-creted dirt floor, table, sleeping platform lurking under which, according to an old log book, is said to be a resident snake. This, undoubtedly, a rumour spread by its caretakers, the Illawarra Alpine Club, to deter those new-age mountain biking people and bushwalking riff-raff from sleeping in the hut.

The Illawarra Alpine Club have been Caretakers for Cascade, Tin Mines and Teddys Hut for over 40 years. A sterling effort and a job well done in maintaining these basic mountain shelters for the safety of bushwalkers, mountain bikers and skiers alike.

Unperturbed by the resident snake, we settled in anyway. First order of business, the peons spread out to collect water and fetch the firewood. Brian sawed the logs into useful sized billets. Just so. His favourite camp thing to do. Joe was tasked with lighting the fire. Finally, tents sprang up on the springy snow grass.

On dusk, five Gang-gang Cockatoos trailed above us, slow powerful wing beats. Impossible to mis-identify these distinctive dark grey cockatoos, the males sporting red heads and wispy red crests.

We whiled away the evening reading the log book, including a scary account of a dingo getting close up and too friendly with a solitary walker, not far from Cascade Hut. His advice: walk briskly and carry a bloody big stick.

Tuesday: Cascade Hut to Teddys Hut via The Big Boggy: 15 kms.

A coolish morning with bushfire haze from the Victorian fires lingering in the valley below. Our Gang-gangs flew back overhead from whence they had roosted.

Brian’s original plan was that we would go cross-country to Teddys Hut via Jerusalem Hill (1810 metres) on the spine of the Great Dividing Range. From Jerusalem, our track would follow the GDR spine north-west for several kilometres to an outcrop at 1806 metres, from which we could drop into the Big Boggy on the upper Thredbo River. But a quick perusal of the thickly wooded hillslopes in front of us and the map’s ortho image disabused us of that option.

Instead we chickened out and retreated up the Cascade Trail to Bobs Ridge. From here, we could swing off the trail and wander over the top of that un-named knoll on the Great Dividing Range (1806 m) and drop into the Thredbo River (formerly the Crackenback) at the Big Boggy (aka Boggy Plain).

The Crackenback River is said to take its name from stockmen who herded their mobs of sheep and cattle up onto the Main Range from the Crackenback (Thredbo) Valley. It was rugged, difficult country and it was said it would ‘crack-your-back’. Another version was that stockmen had to crack their whips across the backs of the stock to get them to the high tops.

We pulled in for lunch at a clump of snow gums on the crest of the Great Dividing Range, at our prominent un-named hill. Before us were sweeping northerly views across to the Rams Head Range and the Main Range.

Lunch over, we began a longish bush-bash down to the sodden edge of the Big Boggy. Here we swung east, contouring along the southern edge of the Thredbo River and the Big Boggy.

The plan was to aim for the extensive grassy plain that separates the Thredbo River headwaters from the Wombat Gully-Mowamba River System. Some four kilometres upstream.

The Big Boggy is a massive alpine wetland and frost hollow which, although outstandingly scenic, made our afternoon’s upstream walk to Teddys a bit damp underfoot and pretty tedious.

Teddys Hut

Teddys, once called My Horse Hut, served as a cattlemens’ and brumby runners’ hut and was built by Teddy McGufficke and Noel and Dave Prendergast in 1948. Teddys lies at the headwaters of the Thredbo, a tributary of the Snowy River and is the only shelter on this isolated and often snow-bound plateau.

According to the old timers it was on a sort of brumby motorway and clearly nothing much has changed over the decades. We watched as Serengeti-like herds of brumbies grazed peacefully on the vast snow grass plains in the vicinity of this remote hut.

Wednesday: Day Walk to The Chimneys and Chimneys Ridge: 8 kms.

For once, an easy day. In the overall scheme of Brian’s pantheon of dubious ‘rest days’ this one was brilliant. As we tucked into a leisurely breakfast even a bank of dense, damp fog hanging around Teddys rolled ever so slowly away from us, down the Mowamba River system. A promising omen of a great day’s walking.

The Chimneys and Chimneys Ridge form the divide between the Thredbo River and the Jacobs River, also a Snowy River tributary.

The Chimneys: 1885 m

The Chimneys (1885 metres) rise, tooth like, a jumble of granitic boulders that are said, with a considerable stretch of the imagination, to resemble chimney pots on old houses. They are outcrops of Silurian Mowambah Granodiorite (age range 444 million years ago to 419 Mya). The view must be one of the finest in Kosciuszko. As a bonus, nary a backpacker, mountain biker, or tourist to clutter up our summit views.

To the south was the deep valley of the Jacobs River with the Snowy River in the distance. The Pilot Wilderness area stretched out in a row of five hills: Purgatory, Jerusalem, Paradise, Wild Bullock and Stockwhip. With The Pilot (1829 m) and the Cobberas even further south.

To the north we looked to the Rams Head Range and the Main Range of Kosciuszko. Hundreds of metres below us were extensive views into the alpine grasslands, bogs and fens of the upper Thredbo valley.

The Crackenback Fault

The course of the Thredbo River presents an interesting drainage pattern when viewed on a map. It is described by geomorphologists as a rectilinear drainage pattern, where the main bends of the Thredbo River change direction at right angles. In the case of the Thredbo, it initially flows south-east, then turns south-west, then north-west and finally into the main valley which runs north-east to Lake Jindabyne.

Rectilinear drainage pattern of Thredbo River. Position & influence of Crackenback Fault.

All these changes of direction are controlled by a complex system of joint lines and faults which are both significant elements in the evolution of the Snowy Mountains landscape.

Joint lines are structures along which there has been no discernable differential movement. Large scale joints are are common feature of granitoid landscapes, like the Chimneys Ridge.

Faults, however, show clear evidence of differential earth movements. The Crackenback Fault is a 35 kilometre long south-west to north-east trending strike-slip fault between the Jindabyne Thrust Fault (at Jindabyne) and Dead Horse Gap. It is a consequence of the Tabberabberan tectonic contraction (390-380 mya).

A strike-slip fault has horizontal movement of the earth’s surface with little vertical displacement. It is along this straight fault structure that the Thredbo River flows towards Lake Jindabyne.

Our return to Teddys was along the spine of the Chimneys Ridge. At nearly 1900 metres, this was a cool and pleasant ramble across snow grass meadows interspersed with outcropping granitic pillars. At Smiths Gap we propped and then looped north, descending to Teddys. One and a half kilometres away, but not visible.

No takers for Brian’s suggestion for an afternoon nip up Mt Terrible (1850m). A predictable response. Maybe we had been ambushed too many times before by Brian’s predilection for hikes to places with dodgy names like Furnace Creek, the Never-Never, the Madderhorn, Heartbreak Ridge, Perdition Plateau, Hurricane Heath, Snake Hill, Tornado Flat and Corruption Gully .

Mt Terrible was climbed by explorer John Lhotsky who named it Mt William IV, claiming it to be “the highest point ever reached on the Australian continent”. Historians are divided on whether he did, in fact, climb Mt Kosciuszko. The general consensus is that he probably did see Mount Kosciuszko 13 kilometres to the north-west but never climbed it. Lhotsky had better luck with his naming of the Snowy River, the placename which is still used. “I flatter myself that I am the first writer introducing this river into geography”.

It was Sir Paul Edmund Strzelecki who had the non-indigenous bagging and naming rights to Mt Kosciuszko, which he ascended (with others) in 1840. Though some historians believe he actually climbed Mt Townsend, the second highest peak in Australia.

But, who was Kosciuszko? Well might you ask why is Australia’s highest mountain named after a Polish freedom fighter? Tadeusz Kosciuszko (1746 – 1817) was a Polish military engineer, freedom fighter and hero of the American War of Independence and his native Poland. He inspired George Washington and was friends with Thomas Jefferson. Short story: Tadeusz Kosciuszko was a thoroughly admirable human being.

Read about Kosciuszko and the mountain in Anthony Sharwood’s: Kosciuszko, the Incredible Life of the Man Behind the Mountain.

And so to Teddys. For me, an afternoon of indolence, lying around on my Thermarest banana lounge with nought to do but eat, drink, read and watch the grazing brumbies. But the inside of the hut was a happening place.

Joe and Noel were busy indoors engaged in epic DIY projects. Like constructing temporary seating, benches and shelves. Shuffling blocks of wood and milled planks around and around and around. Or in long-winded discussions on ways for the KHA maintence volunteers to wind-proof the slab walls. Exciting stuff like that.

For me, as I lounged on the snow grass at the front of the hut, I could see that old McGufficke’s siting of this hut was a stroke of genius. The front doorstep opened out onto beautiful snow grass plains, gently sloping down to Wombat Gully. In the far distance I watched dark rain squalls sweeping over Drift Hill and hoped the weather would be fine for our last day tomorrow. Nothing is ever a certainty with high country weather.

Thursday: Teddys to Thredbo via The Brindle Bull: 8 kms.

This is an outstanding alpine walk, climbing quickly through the tree line then out onto vast alpine meadows. Occasional granitic outcrops rise above the meadows.

We planned our route from Teddys to take us four kilometres west-nor’-west up into the headwaters of the Thredbo River, then across to the Brindle Bull Hill. From its summit we would swing right to the north-east for another four kilometres to drop into Thredbo village at Friday Flats. It was an immensely satisfying walk for our last day.

The navigation was straightforward enough. Follow the Thredbo River up to its source, dodging Mt Leo (1875m) to our south, keeping Adams Monument (1908m) well to our right. No problems with that.

From the gap we continued beetling west, on a tour of outcrops standing at 1800 plus metres. And there ahead of us, apart from yet more brazen brumbies, was the domed form of the Brindle Bull Hill (1872m). Brian and the lads could legitimately claim another 1000 metre peak.

Brian indicated an easy route up that would have us contouring up to the summit tors. But he immediately ignored his own advice and departed posthaste up the closest vertical granite slab leading to the summit.

Clearly he has a different concept of ‘easy’ and ‘contouring’ to the rest of the hiking universe. But the herd instinct kicked in and like dumbclucks we followed anyway, somehow juggling the clutter of map cases, compasses, cameras and walking poles as we hauled ourselves up for a well-earned breather on the summit.

The Brindle Bull

The treat was the expansive views south to The Chimneys and The Pilot and off to the north-east, the Rams Head Range from our previous throughwalk.

Our final leg snaked down a four kilometre ridge to the Alpine Way (1400m) just above Thredbo Village. Joe, Richard and Noel, brandishing multiple GPSs, made sure that their old-school navigators stayed on track in order to gain the correct ridge down to Friday Flat. So we confidently contoured around BB5 (Brindle Bull 5) and BB6, climbed over the top of BB7 and BB8.

This led us finally to BB9, our exit point (at 1660m). But as Brian and I had learnt from a previous experience of coming off nearby Paddy Rushs Bogong, the drop to Thredbo was never going to be plain sailing. Intelligence that we failed to share with our companions.

The vegetation changes from open alpine meadows to a snow gum woodland with a dense scrubby understorey of beastly spikey stuff like Bossiaea, Epacris, Hakea, Grevillea, Oxylobium, and Kunzea . Here’s where those knee-length canvas gaiter things worn by Australian bushwalkers are a brilliant piece of kit.

This undergrowth is called Tall Alpine Heath and is waist-high with tough whippy branches to withstand the weight of snow (and, hopefully, bushwalkers) without breaking. Throw in torpid highland copperheads and pit-fall traps of wombat and bunny burrows, and the Alpine Way to Thredbo couldn’t come fast enough for me.

So, a tad before 2.00 pm, five dishevelled bushwalkers burst through the thick brush and out onto the Alpine Way. Startling a young headphoned damsel who was out enjoying her daily power walk along the Alpine Way.

For us, two weeks of superb alpine walking were over. Anyone for a Kosciuszko Pale Ale?