by Glenn Burns

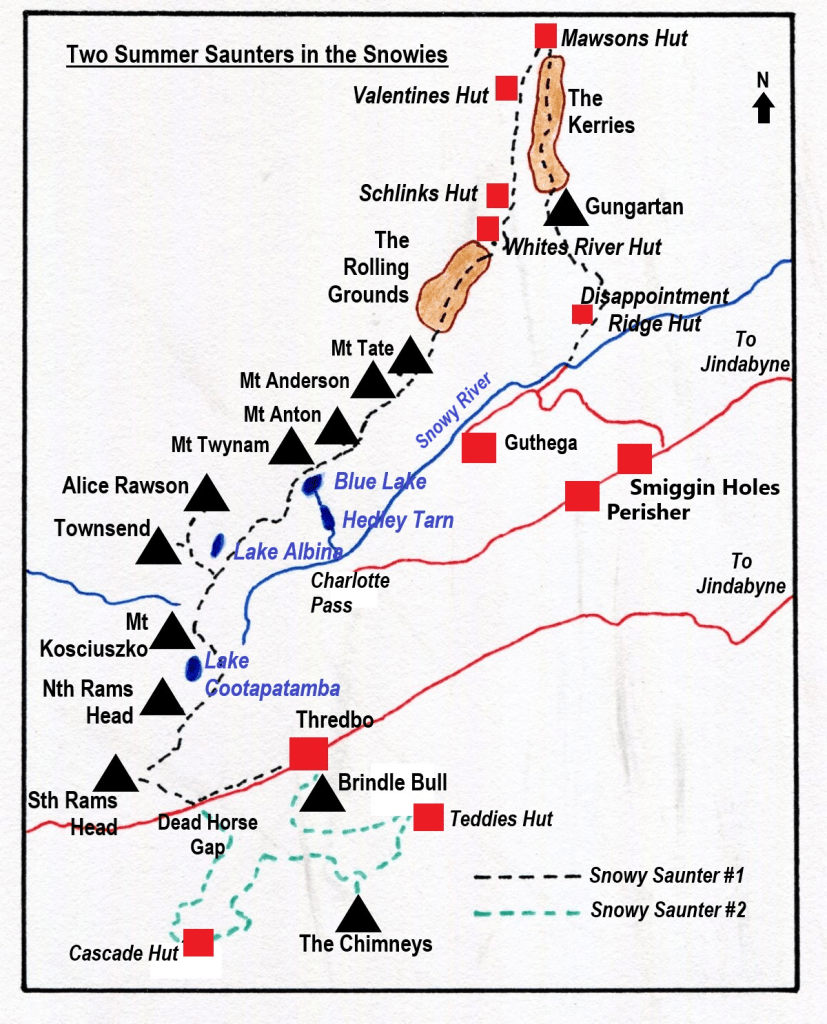

In 2018 construction started on the 55 kilometre Snowies Alpine Walk. The NSW Government boasted it would deliver ‘ a world-class, multi-day walk across the alpine roof of Australia in Kosciuszko National Park.’ The twelve kilometre hike from Perisher to Bullocks Flat is the final section of this longer walk. The hike traverses Kosciuszko National Park’s high alpine zone before descending hundreds of metres through snow gum woodland and dense eucalypt forest to the Thredbo Valley.

In its entirety, the Snowies Alpine Walk (SAW) connects Charlotte Pass, the Main Range, Guthega, Perisher and Bullocks Flat. The Perisher to Bullocks Flat section was the last part of the Snowies Alpine Walk to be constructed and was opened in the summer of 2024. Just in time for me to test drive it. And I was impressed.

It starts in the village of Perisher and finishes at the Thredbo River near Bullocks Flat. The track takes walkers from the alpine zone to a lookout high above the Thredbo River valley before a steep descent of the Crackenback Fall to reach the swiftly flowing waters of the river. From here the track follows the Thredbo upstream to Bullocks Flat, a popular day use area.

Perisher Village, my starting point, Is a small alpine village. In winter it is a picture perfect mountain village with architecturally interesting ski lodges, manicured snow runs, lifts and surrounded by snow-capped mountains. It takes its name from from one of these mountains, Mt Perisher.

Mt Perisher was named by an early pastoralist, James Spencer, who, while chasing lost cattle with his stockman, climbed to the top of the 2054 metre peak for a better view. On the summit he was met by scuds of snow and an icy blasting wind, upon which he commented: “This is a bloody perisher.” Later they climbed the adjacent peak, The Paralyser and the stockman remarked, “Well, if that was a perisher, then this is a paralyser.

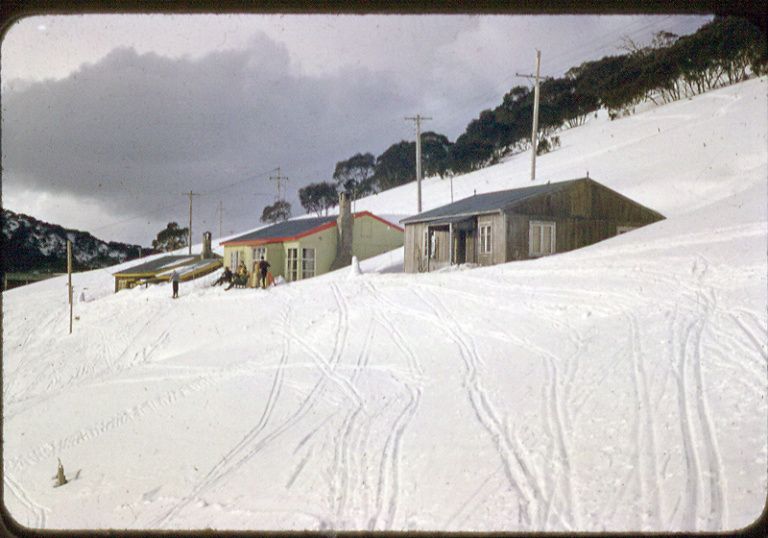

Perisher, in summer, is a less attractive proposition. Yet another man-made blot on an otherwise outstanding alpine landscape. Its development as a ski resort took off at the time of the Snowy Mountains Scheme. The Snowy Mountains project provided access roads, work camps including one at Perisher and an influx of skiing mad European migrants to work on the scheme. Perisher was born.

As my erstwhile walking companions, sons and grandchildren, had already deserted for greener pastures, I was on my lonesome for this section. My wife provided the vital taxi service connecting my drop off point at Perisher Village with Bullocks Flat. A road trip of some 50 kilometres. Otherwise, it is a return hike to and from Perisher of some 24 kilometres and 740 metres of altitude gain.

I had the track basically to myself. There were two other walkers that day, young women who had walked the Charlotte Pass to Perisher section the previous day. And this was peak summer walking: great walking weather, wildflowers galore and school holidays. In my experience, the other sections of the SAW were always busy in summer. But, today, not the Perisher to Bullocks Flat track.

I started early, about 8.00 am. Blue skies and a very pleasant 8oC greeted me, without the blustery winds of previous days. It is an ideal half day walk winding through a magnificent landscape of alpine heath meadows, snow gum woodland, and a montane Eucalypt forest including stands of alpine ash. The track weaves in and out of huge granite tors before descending to reach the pristine waters of the Thredbo River. As a bonus there is the Thredbo lookout perched some 600 metres above the valley floor.

The walk starts at the Perisher village track-head sharing the Charlotte Pass/ Porcupine Rocks track. After a few hundred metres my path cleaved south east following Rocky Creek.

The track then climbs steadily through Snow gum woodland with occasional patches of alpine heath. As I crossed the last of the heath, my map showed the line of the Ski Tube tunnel … under my boots, but some hundreds of metres below.

Ski Tube

The Ski Tube is a Swiss designed electric rack railway that connects Bullocks Flat and Blue Cow via Perisher village. It departs from the Bullocks Flat terminal (1134 m) before entering the Bilson tunnel that ascends to Perisher Villager (1720 m), with another tunnel connection to Blue Cow (1910 m). The 5.9 kilometre section from Bullocks Flat to Perisher was opened in 1987, while the 2.3 kilometre Blue Cow section opened in 1988.

From a high point at 1800 metres the track begins its long descent, initially through snow gum woodland, towards the Thredbo River. Some 3.5 kilometres from Perisher is the Thredbo Valley Lookout. This vantage point gives extensive views into the Thredbo Valley some 700 metres below with the Monaro Plain off to the east. Klaus Hueneke in his excellent tome “Huts of the High Country” gives this derivation of Monaro: ‘ Aboriginal for gently rounded woman’s breasts like the undulating country around Cooma. Also spelt Monaroo,Miniera Maneiro, Meneru and Monera’

It was here that I came across the two young women again who were lounging on the lookout deck having a bite to eat. They didn’t seem in any hurry to leave and not wanting to intrude, I wandered off to find a sunny morning tea spot of my own. A nearby elevated slab of granodiorite at 1700 metres with equally spectacular views fitted the bill. Perfect.

From here the track descended gently north east for 2.5 kilometres to the 1500 metres contour before switch-backing south west to drop steeply for 3.5 kilometres to the Thredbo River at 1100 metres. This was more in the category of a bushwalker’s pad rather than the heavily engineered tracks found on other sections of the SAW. The descent from the lookout takes you over the Crackenback Fall, a major geological feature of Kosciuszko National Park.

Crackenback Fall

From the lookout the Crackenback Fall drops 700 metres to the Thredbo River valley. This spectacular fall can be explained by a combination of tectonic uplift (called the Kosciuszko Uplift) during the Tertiary (66 to 2.6 mya) and the rapid downcutting of the Thredbo River into the shattered bedrock along the straight line of the Crackenback Fault. The Crackenback Fault dates back to a major tectonic contraction during the Lachlan orogeny some 390 to 380 mya.

Klaus Hueneke in : “Huts of the High Country” writes: “stockmen who brought cattle and sheep on to the main range from the Thredbo valley over difficult terrain often said ‘it would Crack-your-back.’ Others said you had to crack the whip across their backs to get them up there.” The name was applied to the river, the Crackenback River which was later changed to the Thredbo River.

Position of Crackenback Fall

Vegetation Zones of the Crackenback Fall

As you descend the Crackenback Fall the vegetation changes from tall alpine herbfields on the high tops through a belt of snow gum woodland, thence to mixed Eucalypt forest before finally reaching a riparian shrub zone on the banks of the Thredbo River.

Tall Alpine Herbfield

The tall alpine herbfields are the most extensive of all Kosciuszko’s alpine plant communities and are found on well-drained and deeper soils. They are found on Kosciuszko’s highest peaks, plateaus and ridges, in conjunction with swathes of grassland, low heathland and bogs. These apparently delicate plants must withstand freezing rain, sleet, blanketing snow, howling winds, as well as heat and extreme UV radiation. Maybe not so delicate.

This plant community is the most diverse of all the high alpine vegetation types in terms of number of species. Showy wildflowers grow in a matrix dominated by the genera Celmisia (daisies) and Poa (snow grasses).

Wildflowers which I recognised included: silver snow daisy (Celmisia astelifolia), Australian bluebells (Wahlenbergia spp), star buttercups (Ranunculus spp), bidgee widgee (Acaena anserinifolia), Australian gentians (Gentiana spp), eyebrights (Euphrasia spp), billy buttons (Craspedia uniflora), and violets (Viola betonicifolia).

Snow Gum Woodland

The low growing snow gum woodland is found above 1500 metres, the winter snowline. It is dominated by snow gums or white sallee (Eucalyptus pauciflora). Its growth habit is low, twisted, stunted and bent away from the prevailing winds. Snow gum woodland is invariably clothed in a dense scrubby understorey of beastly spikey plants like Bossiaea, Epacris, Hakea, Grevillea, Oxylobium, and Kunzea. These are usually waist high with tough whippy branches. This, presumably, an adaptation to withstand the weight of snow or overly rotund bushwalkers without breaking.

Mixed Eucalypt Forest

Below the tree line zone which is dominated by pure stands of snow gums, comes a mixed Eucalypt forest of snow gum, mountain gum (E. dalrympleana), Tingiringi gum (E. glaucescens), candlebark (E. rubida), manna gum (E. viminalis), and alpine ash (E. delegatensis).

On your descent through the zone of Eucalypts you will encounter some nearly pure stands of alpine ash. This species is typically found between 1200 to 1350 metres on wetter south and south-easterly facing aspects. It is an unusual Eucalypt in that it does not have any specialised fire survival techniques (such as epicormic growth) and regenerates from seed after fire has destroyed surrounding heavy leaf litter which usually inhibits seed germination.

Riparian Shrubland

A diverse plant community of mainly shrubs occupies a narrow a strip alongside the Thredbo River. The main canopy species is an olive-green trunked gum called black sallee (E. stellulata). Occasional pockets of mountain gum and black sallee grow together. But the main botanical action is in the shrub layer which provides a profusion of wildflower displays in early summer.

Along the track as you work your upstream towards Bullocks Flat, here are a few to look out for: poison rice-bush (Pimelea pauciflora) with small slender leaves, creamy flowers and orange fruit; mountain tea-tree (Leptospermum grandifolium) with 5 petalled white flowers, forming dense thickets along the banks, and close to the river, alpine bottlebrush (Callistemon pityoides) with its distinctive brush flowers.

Useful reference book on plants in the Thredbo Valley

This handy little guide to plants in the Thredbo Valley won’t take up too much space in your rucksack (15 cm x 21 cm).

Thredbo River aka Crackenback River

On reaching the Thredbo River, the track closely parallels the river for a further one kilometre to Bullocks Flat, which is accessed by the Ski Tube bridge over the Thredbo River near the Ski Tube carpark. An eyesore of monumental proportions. How the Parks service gave planning approval for this hideous monstrosity is a mystery. Or maybe not. The slimy hands of NSW politicians would be at play in boosting ski tourism in the national park. A pattern of pandering to the ski industry that is repeated across most of Australia’s alpine ski fields.

But moving on from this well-ventilated gripe of mine. If you look upstream and downstream from an opening onto the river bank you will see how straight the course of the Thredbo River is. In fact, it flows in a reasonably straight line from Dead Horse Gap to Lake Jindabyne. A consequence of the structural control exerted by the Crackenback Fault.

The course of the Thredbo River presents an interesting drainage pattern when viewed on a map. It is described by geomorphologists as a rectilinear drainage pattern, where the main bends of the Thredbo River change direction at right angles. In the case of the Thredbo, it initially flows south-east, then turns south-west, then north-west and finally into the main Thredbo valley which runs in a straight line north-east to Lake Jindabyne.

Faults show clear evidence of differential earth movements. The Crackenback Fault is a 35 kilometre long, south-west to north-east trending strike-slip fault between the Jindabyne Thrust Fault (at Jindabyne) and Dead Horse Gap.

A strike-slip fault has horizontal movement of the earth’s surface with little vertical displacement. It is along this straight fault structure that the Thredbo River flows towards Lake Jindabyne.

Other well-known strike-slip faults include New Zealand’s Alpine Fault, the Dead Sea, and the San Andreas fault in North America.

Enter the World of Willie the Wombat

The walk upstream is an opportunity to keep your eyes open for signs of those bulldozers of bush and plain, wombats. You have to be lucky to chance upon a trundling wombat during the day, but their massive burrows, or their very distinctive cuboid poos are easily spotted. The common wombat (Vombatis ursinus: bear- like) is of tank-like stature: about 100 cm long, 30 kilograms in weight, short stubby legs and thickset body. The fur is coarse and of a grey, black or brown colour.

They are herbivores grazing on grasses, roots and fungi. Their teeth grow continuously to accommodate their gnawing on rough herbage and roots. In summer they leave their 10 to 15 metre long burrows on dusk and graze through the early part of the night. On one trip to Kosciuszko we spent quite a long time at dusk in the nearby Thredbo Diggings area hoping to spot a wombat for our little boys. A futile venture as it turned out. Plenty of fresh poo and burrows, but alas no Willie Wombat.

The preferred habitat for wombats is woodland or grassland but they can be found foraging above the tree-line. One was spotted ascending Mt Townsend at 2209 metres, Australia’s second highest peak.

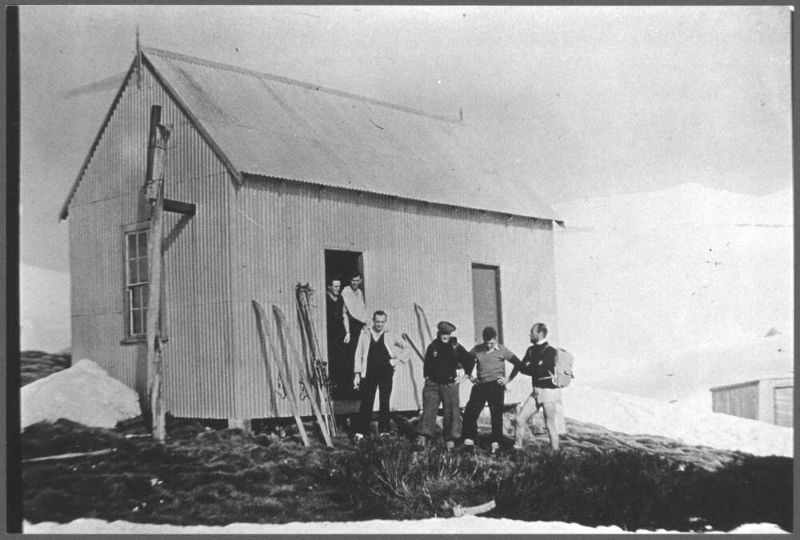

Bullocks Flat and Bullocks Hut

Bullocks Hut is on the banks the Thredbo River near that ugly Ski Tube car park. Quite a contrast. This is an enticing site of grassy flats and the picturesque fast flowing Thredbo River. Bullocks Hut was built in 1934 for Dr Bullock as a fishing lodge and used by the family until about 1950. A kitchen was added in 1938 and a garage and stables in 1947. The hut was resumed by the NPWS in 1969 and renovated in the 1990’s.

It is described in various publications as ‘built like a fortress’. As it is. The walls are constructed of cement blocks with the floor of tiles over a cement base. The original roof was constructed of shingles cut by a Snowy Mountains local identity, Bill Prendergast. The roof was later covered by sheets of iron. The chimney is made of cement. The use of cement has resulted in the hut being fenced off & declared out of bounds. Due to an OHS issue… silica dust contamination.

The Crackenback Gold Rush

Bullocks Flats was just one of the many river flats and river banks (like the nearby Thredbo Diggings campground) that were dug and sluiced for gold. The Crackenback gold rush took off in the 1870’s when small tributary streams were worked over by gold miners. The diggings were so remote that it took two months for bullock teams and drays to bring supplies from Sydney.

The last remaining miner was Alf Tissot who worked the area until the late 1930’s. Like many miners, he preferred to walk rather than ride the 20 kilometres into Jindabyne to get his supplies.

Look carefully and you will see flecks of gold and silver in the sandy riverine deposits. Unfortunately for you, this is merely ‘Fools’ Gold’, aka Pyrite or Chalcopyrite or Mica.

Iron Pyrite (Iron sulphide) looks like gold but is a pale brassy colour and isn’t malleable. Also pyrite forms perfect cubic crystals and if you scrape pyrite down a scratch plate it leaves a geenish-black powder rather than flakes of gold. Pyrite gets its name from the Greek ‘pyr‘ meaning fire, because it emits a spark when struck by iron.

Chalcopyrite (Copper pyrite) is a bright, brassy-yellow mineral, which tarnishes to a dull gold colour. Unlike gold it is brittle and breaks easily.

Mica is very common in the Thredbo River. and is derived from the local granitic bedrock. Any gold sparkles are the first two, but the silvery or yellowy-brown sparkles are most likely mica.

It is easily identified. You won’t be fooled for long. When split, mica cleaves into thin sheets or laminae which sparkle silvery or vaguely gold in sunlight. It has a wide variety of uses including in the manufacture of electronics, paints, plastics and cosmetics.

In the 1910’s and 1920’s Ned Irwin’s sawmill operated on the opposite bank from Bullocks to source the towering hardwood eucalypts, especially the alpine ash. Bullock teams dragged the timber into nearby towns for housing materials. There is supposed to be an old steam engine and flywheel in the area, but I didn’t see them.

Rutledges Hut

Several kilometres upstream from Bullocks Flat is the site of Rutledges Hut, now removed, another fisherman’s lodge. This was built in 1935 by a Colonel Rutledge and his fellow fishers Mr McKeown, Brigadier Broadbent and a Mr Burns. It was a long hut constructed of sheet iron and had a wooden floor. It was removed by the NPWS in the 1980’s, deemed unsafe. The NPWS was pretty keen on removing huts for a while.

In 1979 the NPWS issued a draft huts policy which created a huge, well-deserved backlash. They recommended removal of all huts in the summit area (except Seamans) and in the Whites River corridor (except Disappointment and Whites River Huts). In addition, the demolition of O’Keefes, Grey Hill Café and Tantangara were pencilled in. They were forced to back off, but removed Albina and Rawsons, the sacrificial lambs.

Fortunately, times have changed and the NPWS together with the Kosciuszko Huts Association is now heavily invested in conserving these heritage shelters for the use of bushwalkers and skiers needing a place of sanctuary in the oft changeable alpine weather.

Fishing on the Thredbo River

Fishing has a long history in the Snowy Mountains, especially fly fishing. The quarry was not the native mountain trout (Galaxis olidus) which struggles to reach to 10 cms in length, but the introduced North American Rainbow trout (Oncorhyncus mykiss) and the European brown trout (Salmo trutta). These were introduced in the 1890’s and are restocked regularly from the Gaden Trout Hatchery further downstream. An unfortunate outcome of these introductions has been a profound change in the local aquatic ecosystems with Galaxias missing from streams inhabited by trout. They are now confined to a few high alpine streams and lakes.

By midday, my walk on this final section of the Snowies Alpine Walk was over. I found a bench seat in a sunny spot near Bullocks Hut and waited for the wife taxi and accompanying lunch supplies to arrive. A pleasant warm spot for us to eat, chat and, ever the inveterate cartography nerds, check off the landmarks from our map: the Rams Head Range, The Porcupine at 1921 metres, the Thredbo Lookout and the entrance to the Bilson Tunnel.

Aboriginal Occupation Of Thredbo Valley

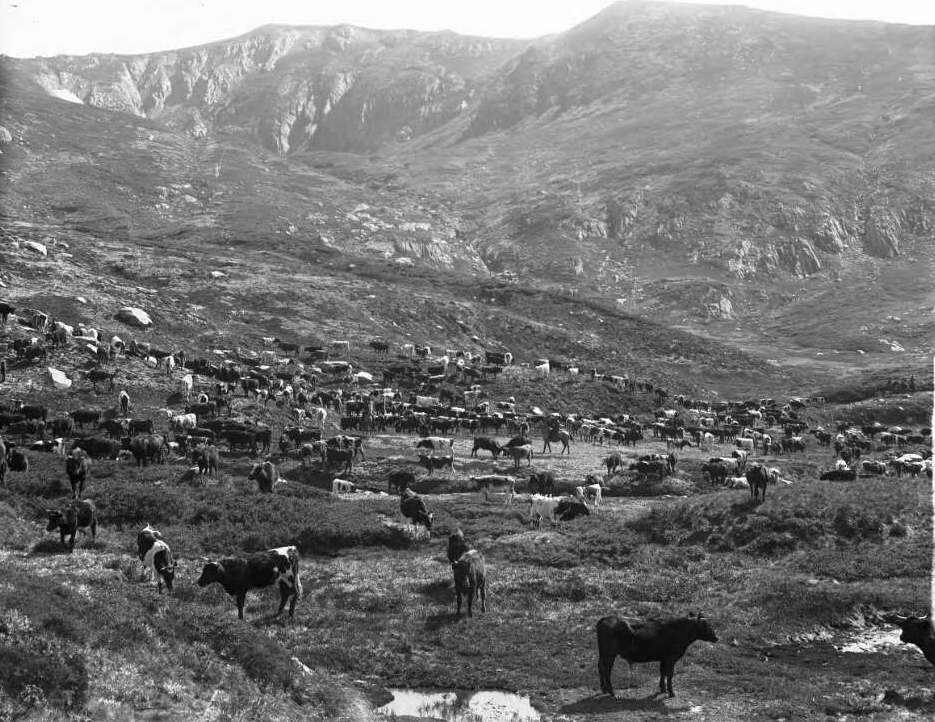

Long before the unthinking predations of gold miners, loggers, fishermen, and cattlemen the Thredbo River valley was traversed by aborigines. Lithic scatters have been found near Bullocks Flat and other sites in the along the Thredbo. These scatters including stone hammers, scrapers and flakes. Waste lithic material accumulated in favourite campsites and these can be found if you are alert. Though they must be left in-situ.

During summer the Wogal tribe gathered in the valley, along with other tribal groups to feast on the bogong moth. Moth feasts were a great occasions for gatherings of friendly tribes. They were summons by message sticks to join the feasting, corroborees, trade, settling of disputes and marriage arrangements.

The gatherings took place at the foot of the mountains. The aborigines came from Yass and Braidwood, from Eden on the coast and from Omeo and Mitta Mitta in Victoria. All intent on having a good feed and a good time. Large camps formed with as many as 500 aborigines .

It is thought that advance parties would climb up to the tops, and if the moths had arrived they would send up a smoke signal to the camps below. The arrival of the moths is not a foregone conclusion. Migration numbers vary from year to year.

Some years they are blown off course and out into the Tasman Sea. 1987 was a vintage year, but in 1988 the bright lights of New Parliament House in Australia’s bush capital, acted as a moth magnet, and they camped in Canberra for their summer recess, unlike our political masters.

Men caught the moths in bark nets or smoked them out of their crevices. They were generally cooked in hot ashes but it is thought that women sometimes pounded them into a paste to bake as a cake. Those keen enough to taste the Bogong moth mention a nutty taste.

Scientists say they are very rich in fat and protein; this diet sustained aborigines for months and the smoke from their fires was so thick that surveyors complained that they were unable to take bearings because the main peaks were always shrouded in smoke.

Europeans often commented on how sleek and well fed the aborigines looked after their moth diet. Edward Eyre who explored the Monaro in the 1830’s wrote: “The Blacks never looked so fat or shiny as they do during the Bougan season, and even their dogs get into condition then.” At summer’s end, with the arrival of the southerlies, the moths and aborigines all decamped and headed for the warmer lowlands. As did I. Back to the the heat and humidity of Queensland.

Should you want to read more about aboriginal moth hunters , then you should delve into Josephine Flood’s ‘Moth Hunters‘.

For me, it was another brilliant walk in Australia’s high country done and dusted.