by Glenn Burns.

Photos by Samantha Rowe and Glenn Burns

Girraween National Park has long been one of my favourite bushwalking haunts. Its springtime wildflower displays, rugged granite landscapes and frosty climes make for superb walking adventures.

Nestled in the western section of the park, abutting the Queensland-New South Wales border is what I consider the best of Girraween: spectacular granite domes rising to over 1200 metres, extensive swamps, creeks cascading down smooth rock slabs, wildflowers in profusion, and always the possibility of sighting a Superb Lyrebird, or perhaps a solitary dingo, or maybe, just on dusk, a wombat trundling across creek flats.

The name Girraween, “place of flowers” dates back to the 1960’s when a public naming competition was held for the enlarged national park (11,800 hectares). A prize of $50.00 was offered and the winning name was “Girraween”. Disappointingly, it is not a word in a local aboriginal dialect, even though a number of aboriginal groups appear to have lived in and travelled through the area: the Kambuwal, Jakamabal, Kwiambal, Ngarabal and the Gidabal.

The Stanthorpe district was thought to have been on a significant trade route from the western plains to the east coast, and on a north-south pathway to the Bunya festivals in South East Queensland. The Park info centre displays a few aboriginal artefacts collected locally including axe heads, grinding stones and even a stone implement that had been bartered from remote Papua New Guinea.

Thankfully, several place names in Girraween are aboriginal in origin and some are retained on maps: Bookookoorara Creek, for example, is said to refer to the noise made by a possum and the original name for The Pyramids was Terrawambella, changed, regrettably, to the more prosaic The Domes in 1902, and finally The Pyramids in 1920.

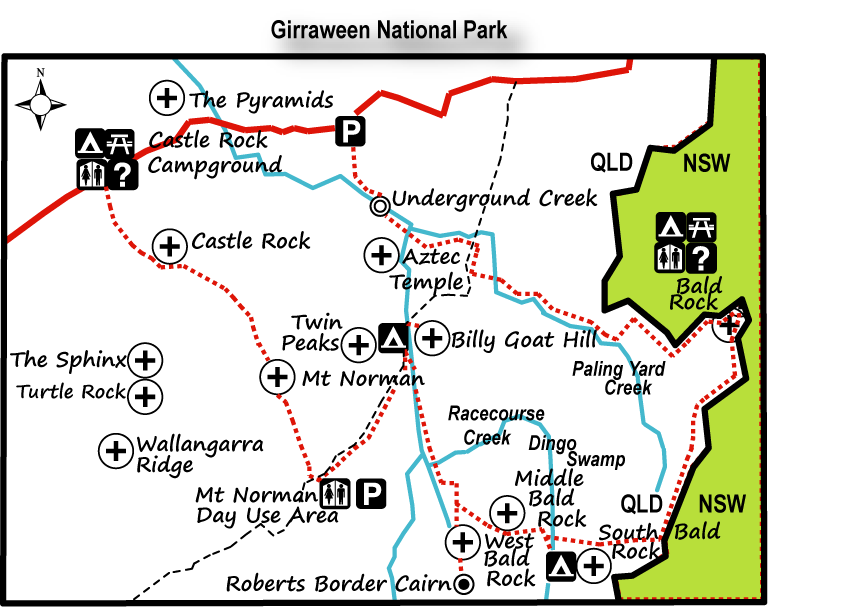

Sunday: Castle Rock Campground to Racecourse Creek: 11 kms.

And so, on a warmish Sunday afternoon at the tail end of September, six walkers, Sam , Peter , Brian , Eva , Joe and their worthy leader, yours truly, set off on the first leg of their 58 kilometre walk through the backblocks of Girraween National Park.

Today’s 11 kilometres would take us to our overnight campsite on Racecourse Creek; but not before stashing supplies for a final night BBQ bacchanal at Castle Rock Campground. Several of my walking companions, who should know better, were foxed by the early start to spring and had strategically downsized to lighter sleeping bags and coats.

Meanwhile, Peter and I ditched our rain gear, gambling on the Bureau of Meteorology’s promised forecast of fine weather until week’s end.

The easy part of the afternoon was walking the tourist track to Mt Norman. But once on the flanks of the mountain I imprudently let Peter convince me that crawling through a 50 centimetre wide crack between massive vertical sheets of granite would be a cool bushwalking thing to do.

Speleologists would call it ‘a squeeze’. For the svelte Sam, trim Eva and even the lean and hungry Peter, this was no drama. But for the three somewhat pudged-up and ageing track dogs, getting irretrievably wedged was a distinct possibility.

Predictably my size 12 Rossi boots got stuck. Comrade Rowe’s suggestion that I should re-arrange my feet ballerina style was a stretched tendon too far. But all in all, it was, as Peter predicted, great fun.

Life in the Fowler fast lane careered on. Peter, Brian and Sam took leave from their more cautious companions and shimmied up a rock slab, teetered along a dodgy looking ledge, hauled up on a sapling and then disappeared from view, heading for Mt Norman’s summit (1267 m).

Some half hour later three bottoms appeared and my friends gingerly lowered themselves one by one onto said ledge. To my considerable relief.

As the sun dipped low to the western horizon we beetled off to find an overnight campsite. On dusk, the sun gone, and the temperature plummeting, we settled into a bush camp on Racecourse Creek where it flows between Twin Peaks and Billy Goat Hill. To my knowledge the only billy goats around were the two-legged variety, minus their down jackets and minus warm sleeping bags.

Monday: Racecourse Ck Camp To South Bald Rock via West Bald Rock: 14.2 kms.

After an early morning jaunt up Billy Goat Hill (1118 m) to defrost (1°C), we shouldered our 15 kilogram monkeys and headed south, following Racecourse Creek upstream towards the Roberts Range and the QLD-NSW border.

It was gaiter central. We puddled along, winding in and out of creek-side thickets and ducking to and fro across the swamp’s edge. Slow progress this. But like all decisive leaders, I had “a” solution. Brian “The Bulldozer” Manuel was recalled to a temporary leadership role and pressed into service at the front, pushing his way through the dense whipstick re-growth.

This is precisely why we keep Brian on the payroll. Strangely, no-one challenged him for pole position. So, with his conga line of five walkers now in tow, Brian led us up Racecourse Creek, executed a hard left hand turn out of the boulder and thicket -choked creek bed and finally stepped out onto the West Bald Rock fire trail.

Not before Eva’s leg tangled with a deep bog-hole in the swamp. But, as I discovered, Eva is a walker of considerable tenacity and she strode on, without complaint, for the remaining 47 kilometres nursing a bruised shin and a wonky knee.

A pre-lunch climb led us to the summit of West Bald Rock (1210 m), rewarding us with hazy views across to our destination for today (South Bald Rock) and on the morrow (Bald Rock in NSW).

And then the highlight of the whole trip. Brian and I wanted to re-locate a nearby border cairn which, it is claimed, had been erected by Surveyor Roberts in the 1860’s during his survey to fix the QLD-NSW border. Brian had stumbled on it years ago and he and I were keen to find it again, although I had suspicions about the commitment of our fellow amateur historians to this venture.

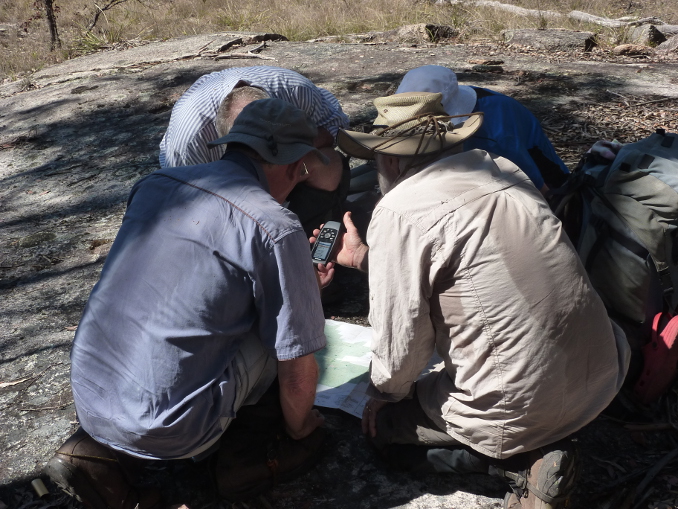

Despite the warm conditions we padded off across sheets of granite and through belts of scrub, heading about one kilometre to the south. With a bit of fancy bush navigation and some black magic from Joe and his GPS we found a fully intact survey cairn (Roberts No 1375), just where Brian predicted.

Bill Kitson and Judith McKay’s tome Surveying Queensland 1839-1945 has an excellent chapter on Queensland border surveys as well as a photo of the cairn.

An afternoon of relaxed pootling along slashed fire trails past Middle Bald Rock delivered us to our campsite under the towering slabs of South Bald Rock. This is an outstanding bush campsite: ample shade, flat tent pads and clear running water in nearby Dingo Swamp.

No dingoes, neither seen nor heard . But what was this… horror of all horrors… a campfires prohibited sign. How will Brian, Peter and Joe possibly survive? Fuel stove only tonight.

As the light faded Sam pointed out that the bright stars hanging in the western sky were, in fact, planets. The brightest, Venus, then Saturn and hanging low to the horizon Mercury. Near Mercury was a star, Spica.

On matters of astronomical trivia, on another late September eve in 1990, the Japanese astronomer Mr Tsutomu Seki of Comet Ikeya- Seki fame, discovered a new 4.7 kilometre diameter main-belt rocky asteroid. Naming rights were given to his friend and colleague in Australia, one Mr Kato who lived near Stanthorpe.

Thus we have asteroid 15723 Girraween, named for Girraween National Park. A more detailed account of asteroid Girraween can be found on the excellent website: www.rymich.com/girraween/.

Tuesday: South Bald Rock To Bald Rock Campsite: 14.35 kms.

Tuesday morning, warmer, a balmy 6°C, causing King Kookaburra, aka Brian, to bestir from his pea-pod yellow tent earlier than usual, soon after 4.30 am according to one of my bleary-eyed informants.

Conversely, a certain other party stubbornly refused to de-tent from his stately MSR pleasure dome until the more civilized hour of 6.00 am. In any event we were still under way soon after 7.00 am for the easy scramble up to the summit of South Bald Rock (1247 m).

South Bald Rock is the classic granite landform, a huge steep-sided domed mass of hard rock, technically referred to as an inselberg. Girraween lies at the northern end of the New England Batholith, an extensive plume of molten magma that cooled slowly deep below the earth’s surface, allowing the formation of rocks with large crystals, adamellite.

Good for boot traction. It is said that the Stanthorpe granites represent one of the most spectacular assemblages of granite landforms in Australia. For the geology buffs among you, an excellent and more detailed account of Girraween’s landscapes can be found in Warwick Willmott’s Rocks and Landscapes of the National Parks of Southern Queensland.

After descending South Bald Rock, we rounded up our now lighter monkeys and ambled off along the shady border trail towards Bald Rock. On this particularly enjoyable morning’s ramble through the shrubby open forest Peter sighted a Lyrebird scratching around in the leaf litter.

The wildflowers were a kaleidoscope of colours: the pinks of Boronias, and Kunzeas; yellow Gomphlobiums and Donkey Orchids; red and yellow pea flowers, and absolutely stunning white and yellow sprays of flowering rock orchids, the mighty kings of the orchid world, Dendrobium speciosum.

As the trail paralleled the border on occasion we played the game of stepping back and forth across the border, QLD-NSW-QLD-NSW-QLD.

Bald Rock Campsite, popular in school holidays, is operated by the NSW Parks Service and offers a well appointed camping ground: a shelter shed with BBQs, toilets, picnic tables, taps, dusty rock-hard tent pads and a big red TOTAL FIRE BAN sign which had Brian, Peter and Joe crying into their beers. Three cans of which Brian had somehow fandangled from a generous Victorian camper, another AFL tragic.

The main feature of the National Park is, of course, Bald Rock (1277 m), Boonoo Boonoo as it was known by local aborigines, meaning ‘big rock’. It is claimed to be the largest inselberg in Australia and also the Southern Hemisphere. We took the refurbished Bungoona Walk to the summit via the well manicured tourist track, only to be nearly blown off the top by a gusting 40 km/h westerly.

Wednesday: Bald Rock Campsite to Castle Rock Campsite: 17 kms.

Warm weather predicted (30°C) for our 17 kilometre walk back to Castle Rock Campsite. We followed the border trail initially, and then swung off-track to follow Paling Yard Creek northwards before fetching up at the Underground Stream (Bald Rock Creek) and the start of the tourist track.

The walk back was relatively easy: traversing open granite slabs, across dry swamp meadows, down Paling Yard Creek and finally connecting with the system of 4 WD management trails that led to the Underground Stream. Paling Yard Creek has some beautiful reaches where it riffles over sheets of granite, and trickles gently down cascades and over small waterfalls to fill tranquil pools below. We propped on one of these for morning tea.

As a finale, we could do no better than the Underground Stream. This is geologically interesting and well worth a visit. Here the creek has eroded swirling spa-like potholes deep into the granite bedrock.

Below, a jumble of massive boulders has choked the creek; the water disappears from view, hence the ‘Underground Stream’. In times of low flow it is possible to climb down and through the boulders.

Nearby granite slabs have been scored by dykes. These are usually narrow linear depressions or ridges in the granite bedrock. They are the result of liquid magma being squeezed along planes of weakness in the bedrock. The magma cools very quickly to form a rock which can be either softer or harder than the contiguous bedrock.

A four kilometre trudge down The Pyramids Road to the Castle Rock Campground knocked some of the gloss off our morning’s relaxed perambulations, but with a decent shower, a feed and one of Joe’s beers to slake our thirst, who could complain.

Late in the afternoon, we saddled up again and headed off for the three kilometre round trip to climb The Pyramid (1080 m). Finally, for those of you who are familiar with this walk, I can report that the famous Balancing Rock is still firmly glued in situ despite Samantha’s determined efforts to unseat it.

More information

B.McDonald et al The Flora of Girraween and Bald Rock( Qld Department of Environment and Heritage Brisbane 1995)

C.W.Twidale Structural Landforms (ANU Press Canberra 1971)

Excellent website: http://www.rymich.com/girraween/

Other hikes in Girraween and nearby Sundown National Park

The Green Gully Track or Snakes Alive

by Glenn Burns

The Green Gully Track is a relatively new 65 kilometre loop walk in the Oxley Wild Rivers National Park in northern NSW. Oxley Wild Rivers takes its name from the explorer John Oxley who passed through this part of NSW in 1802. It offers a brilliant four day throughwalk into the remote Green Gully Creek, a tributary of the Apsley River. The walk lies on the eastern fall of the New England Tableland where the rivers have extensively dissected the escarpment creating a tangled wilderness of gorges, waterfalls and rapids.

And guess what? You can leave behind your tents, therma-rests, stoves and other cooking paraphernalia. The Parks service has refurbished three cattle mustering huts and lashed out to provide stretchers, comfy mattresses, gas stoves, enamel cooking pots, kettles and basic sets of crockery and cutlery. But before you post off your dosh, a $120 booking fee, it is well to remember that this is a trek with several daunting ups and downs, some off-track sections, rock hopping and numerous creek crossings. It is described in that excellent publication of the NSW Confederation of Bushwalkers The Bushwalker as “challenging”. It really isn’t all that hard physically and it is well within the capabilities of any fit walker. But for those of you interested in Australia’s cultural and natural history, this is definitely a walk for you. Parks NSW is to be congratulated on developing this outstanding walking experience in the World Heritage-listed Oxley Wild Rivers.

Tuesday 4 September: Cedar Cottage

Four crusty old track dogs, Brian Manuel (leader), Don Burgher, Richard Mottershead and this scribe travelled to Cedar Creek Cottage at the start of the track, some two hours from Walcha, and south-east of Armidale in New South Wales. It is recommended that walkers stay at Cedar Cottage overnight to ensure a good night’s sleep before embarking on the first 17.5 kilometre leg to Birds Nest Hut. But this is no hardship. It is five star bushwalkers’ accommodation also serving time as a base for NSW firefighting teams. Cottage is a misnomer as it is, in reality, a very comfortable farm house with all modcons including slow combustion stove, hot showers, bunk beds, flushing toilet, fully equipped kitchen, and a smoke alarm with irritable bowel syndrome.

Wednesday 5 September: Cedar Cottage to Birds Nest Hut: 17.5 kms: 6.5 hrs.

We creaked out into a brisk – 4°C morning, heading north-west on the Kunderang Trail. This 4WD management track meanders up and down along a 1000 metre ridge which forms the drainage divide between Kunderang Brook and Birds Nest Creek, reaching 1100 metres at its highest point for the day. Kunderang is an aboriginal name, a clan group of the Thungutti who still maintained a close connection with their land even as recently as the early 1900s, working as stockmen and domestics on nearby properities. It is said that the Green Gully area still has evidence of aboriginal occupation: stone tools, flakes, blades, scarred trees and evidence of occupation in a cave in the nearby Kunderang Valley.

Our first stop was Kunderang Lookout, sporting an excellent information board, the first of many. We peered down into the valley of Kunderang Brook, but it was now wreathed in dense smoke haze from bushfires pushed along by north-westerly winds gusting up to 70km/h.

But this was a fleeting cause for concern compared with the sighting of our first snake, a sleek track-side tiger snake which seemed in no hurry to wriggle off into the undergrowth. Mid afternoon we dropped into Brumby Creek, a tributary of Green Gully Creek and site of Birds Nest Hut at about 900 metres. This was the first of three mustering huts and their extra heavy duty cattle yards. They are an integral part of the story of cattle grazing in these remote and rugged ranges and gorges.

Birds Nest Hut was but one of a system of huts and yards built by the O’Keefe family in the 1950’s to manage their 12500 hectare cattle property, Green Gully. It became part of the Oxley Rivers National Park in 2004, ending another era, that of the cattle stockmen. That is why it is so pleasing to find that the Parks service has maintained the stockyards, fences and huts as a tribute to these hardworking people. And so to relax on our stretchers and mattresses lulled to sleep by the croaking of the endangered Barred Stuttering Frogs in nearby Brumby Creek.

Thursday 6 September: Birds Nest to Green Gully Hut via Birds Nest Trig: 15 kms: 7.5 hrs.

We woke to a coolish 6°C morning, the wind chill from gusty north-westerlies driving the temperature down even further. The first leg of today’s walk is off-track, climbing up a three kilometre ridgeline to 1202 metres, an altitude gain of about 300 metres over one and a quarter hours. An easy enough walk navigationally and physically. Birds Nest Trig was the highest point on our walk and is, in fact, the highest point in the entire Apsley-Macleay system. From here we linked onto The Rocks Trail, a groomed management track. This is a superb walk downhill through Eucalypt forest with a verdant understorey of shrubs and ferns. Here we found a number of large owl pellets, possibly from the Powerful Owl according to my Scats and Tracks book. The trail brought us to The Rocks Lookout, our lunch stop. An opportunity to peer down into Green Gully Canyon some 400 metres below as well providing us with good views of the isolated outcrop of The Rocks at 900 metres and Tooth Rocks (700 metres) across Green Gully Valley.

|

|

Our post prandial leg was one of the hardest of the walk: a 500 metre altitude loss down a long steep ridge line to Brumby Pass and Green Gully Hut. Jelly legs stuff. Perversely, conditions on the open woodland ridgeline were surprisingly hot, despite the wind idling along at 40km/h. But our reward at the end of a hard day was a hot shower, a very comfortable hut and another evening relaxing in front of a blazing log fire. And here was the chance to pick over the obligate knick-knackery that always seems to infest these huts: rusty horseshoes, a drum of Morrison’s Neatsfoot Oil, assorted grimy billies and faded agricultural calendars illustrated with rural scenes or decorous ladies dressed in the matronly styles of the 1960s and 1970s.

Friday 7 September: Green Gully Hut to Colwells Hut: 13.5 kms: 8.0 hrs.

Overnight the gusting wind had not relented but other things had changed. It was time to swap boots for volleys or track shoes and take to the freezing water. One entry in a hut log book whined on about frost forming on walkers’ legs as they waded upstream. Today’s ‘walk’ up Green Gully Creek involved kilometres of rock hopping, inspecting huge boulders of red jasper, wading through a gorge, 41 creek crossings and dodging five more snakes, several being of the best -avoided large red-bellied black kind. And one aggro little sod intent on trying to sink its fangs in, chased me across the rocks. In my hurry to back-pedal away I fell over. Fortunately my rucksack cushioned the fall. Not a good place for an injury or snake bite. But our best sightings were Brush-tailed Rock Wallabies (Petrogale penicillata). This furry fellow with a paintbrush style tail was once abundant in the mountainous parts of Australia but is now an endangered species. Seventy five percent of the remaining colonies of Brush-tails are right here in northern NSW. For more info on our furry friends chase up an article by Inger vandyke: Securing the Shadow Wildlife Australia. Autumn 2009 Vol 46 No 1.

And so to Colwells Hut. A smallish mustering hut. Realistically accommodating only four adults. If you swing by with five or six, then park the excess under the open-sided shelter. There wasn’t enough room for Don to swing Richard’s much doted on cat in this hut and sleeping outside was definitely not a good option on the night we stayed there; it was still very windy with rain threatening. We were driven inside soon after four o’clock by the cool wind but the rain was a total fizzer, a few spits. This was the last of the mustering huts built in The Oxley Wild Rivers, constructed in 1994 by Ian and Nev Colwell to replace Alan Youdale’s 1950s post and bark humpy.

Saturday 8 September: Colwells to Cedar Cottage: 17.5 kms: 7.5 hrs.

Our final day on the track. With a 700 metre climb out of Green Gully this is said to be the most challenging part of the walk. But it is on a 4WD management trail and with light packs it is not too arduous for walkers who have retained some functionality of their knees and ankles. From high up on a 900 metre ridge we looked down into one of the patches of dry rainforest, remnant communities that have species from the great Gondwanan continent. These have survived in cool inaccessible gullies, protected from the ravages of heat and fire. Soon we regained the Kunderang Management Trail and set sail for our final berth at Cedar Cottage. And thus came to an end a most satisfying throughwalk: rambling along through wild high country forests, with spectacular views, remote gorges, Brush-tailed Rock Wallabies and a landscape steeped in the history of cattle grazing.

Photo Gallery

Extra Info:

Cauldwell, Dave: Green Gully: Gorge Raiders. Wild 124.

Green Gully Track Notes. Wild 132.

Inger vandyke: Securing the Shadow. Wildlife Aust. Autumn 2009. Vol 46 No 1. This is an article about the Brush-tailed rock wallaby.

The Jatbula Trail. NT: The Cicada Dreaming

by Glenn Burns.

Tucked away on the far south-western fringes of Australia’s Arnhem Land Plateau is Nitmiluk National Park, a 2928 square kilometre little brother to the World Heritage Listed Kakadu. Nitmiluk, named by a dreamtime ancestor, Nabilil, for the drumming sound of the cicada…Nit! Nit! Nitnit! This landscape belongs to the Jawoyn, freshwater people. It is also home to a major Northern Territory tourist destination, Katherine Gorge. Less well known is Nitmiluk’s 58 kilometre Jatbula Trail, one of the most spectacular remote area track walks in Australia. This outstanding walk climbs up onto the Arnhem Land Plateau and features magnificent views across 17 Mile Creek Valley, Aboriginal rock art, waterfalls, gorges, rapids and secluded rockpools. The Jatbula honours Peter Jatbula, a former drover and aboriginal custodian, who fought to have Nitmiluk returned to its traditional owners in the 1970s and 1980s. It was finally handed over to its traditional owners on the 10th September 1989.

For my money, the Jatbula showcases some the best that Arnhem Land has to offer and even the most blasé trekker will be captivated by its landscapes. And to walk over country that resonates with human occupation stretching back at least 20,000 years is especially pleasurable. The trail is officially ‘challenging’ but for most bushwalkers, once conditioned to the warmer days, it is really quite easy. In the parlance of our leader, Kiwi Ross, it is a ‘spiv’ walk. The first two days traverse the high “stone” country above the escarpment, each day dropping down to a campsite beside placid rockpools, running cascades and roaring waterfalls. The final three days take walkers into the headwaters of the Edith River and then downstream to the campground at Leliyn (Edith Falls).

Wednesday 27 June: Nitmiluk Visitors Centre to Biddlecombe Cascades: 8 kms.

So here we are. Ten throughwalkers sardined into a snub-nosed punt, nudging up to the northern bank of the Katherine River, Jatbula’s trail head. A stone’s throw away on the opposite bank the circus was in town. This was the Nitmiluk Visitors Centre and Campground. A tourist bedlam, bustling with all manner of backpackers, flashpackers, campers, glampers, trampers and tattooed Territorians rubbing shoulders with jaded German jetsetters: all 200,000 of them, most arriving in the five months of the Northern Territory’s cooler dry season.

Our 5.30am campground starts are not universally welcomed. But things could only get better for long suffering fellow campers. And they did. For a start, we vacated the campground soon after 7.00 am allowing our neighbours to catch another ten winks before sunrise. Meanwhile, we had lined up for a surprisingly bargainous breakfast, a poolside buffet. Our chef arrived fashionably late, Top End time. Chef piled our plates with lashings of sizzling sausages, gooey eggs, crispy bacon, crusty toast and sachets of jam and vegemite all washed down with multiple mugs of tea and coffee. Brilliant.

Back on the northern bank our party of eight disembarked: Kiwi Ross, leader; those sirens of the savanna: Linda, Di, Lyn and Sally; Don, an experienced track dog from way back and Brian, his silver-tail sidekick from Peregian Springs. And finally, this pudged-up scribe. Our companion walking party was a couple from Brisbane: George and Mildred. Or was that a TV show from my youth? Graham and Mildred? By walk’s end my brain had it sorted: Marion and Charles or mostly just Charlie. And the best of track companions.

Our first section struck out across a baking savanna woodland heading for the cool oasis of the Northern Rockhole some four kilometres from the drop off. Already the day was firing up to be a stinker. An early departure is the key to enjoying this country and the trick is to trek in winter, start early, drink plenty of water and swim often. We learnt to leave our campsites by 7.30ish when temperatures are a mild 12-14°C and complete the day’s walk by early afternoon. By midday, temperatures are hovering around the 28-30°C mark. Remember that these temperatures are measured in the shade. It is said that above the escarpment, on the stone country, temperatures rise by a further 5-10°C, a fact which I wouldn’t dispute.

Water is the second key element of walking in the Territory. Initially I had hoped to do the daily ten to fifteen kilometres from camp to camp sneaking along on a litre of water. But after our experience in the open savanna on the first morning most of us elected to carry at least two litres from camp to camp. Another useful trick was to dunk hats, heads, shirts and bodies into any rockholes that crossed our path.

Speaking of rockholes, the Northern Rockhole was our first morning tea stop-over. This is a large waterhole where a creek tumbles 50 metres over the escarpment to a deep green plunge-pool below. Distinctly crocodilian. I resisted the temptation to take a dip. Not that I’m aquaphobic but swims could keep until I was over the escarpment and on the plateau. Safely out of the clutches of any peripatetic croc out on a day walk from the nearby Katherine River. Rule Numero Uno of Top End swimming is that pools on top of the escarpment are safe, because crocs can’t, in theory, climb. Pools at the base of the escarpment should always be treated with some suspicion, especially as I had spotted a croc trap while paddling down the Katherine Gorge the previous day.

From the Northern Rockhole the trail follows a 4WD service track as it climbs a long spur up to the plateau at 200 metres, walking us through a snapshot of 1650 million years of Arnhem Land geology. First, past outcrops of volcanics to finally reach the Kombolgie Sandstones which outcrop across vast swathes of the Arnhem Land Plateau. But more of that on the morrow.

We were now meandering through open woodland and spinifex grasslands, sometimes called savanna woodland. This is a harsh dry environment with surface water draining quickly into the sandstone. Scruffy vegetation has adapted to thin and poorly developed soils. Occasional high level bogs and swamps covered with reeds, banksias, grevilleas and even sundews provided a contrast, a pick of green in the drab landscape and fed the permanent streams like Biddlecombe Cascades, our first overnight stop.

We heard the cascades before we saw the campsite, mostly shady with grassy tent sites. And here was our introduction to Mukkul, the green ant. Don pointed out two large arboreal leafy green ant nests woven together with their silky exudates. From here columns of ants marched down the tree trunk and fanned out across the campsite in search of food and human trespassers. Ian Morris in his book Kakadu has an entertaining description of their behaviour: “Green Ants are not particularly tolerant of humans and will respond to a disturbance…. by swarming over the intruder. Their multiple bites are mostly nuisance value…. but their habit of directing a fine jet of acid up to eight centimetres can cause extreme discomfort if it hits the eye.” According to Ross, the Mukkul is a Jawoyn delicacy, much like the honeypot ants of Central Australia or the chocolate-coated ants that my sister had an expensive addiction to. Never one to pass up a good feed, Brian, a well practiced trencherman, chose a large meaty ant but didn’t back up for his usual seconds. And he baulked at squishing their nests which is supposed to make a nice zesty drink when added to water.

The cascades were named after an early gold miner, Biddlecombe. But prospecting was last thing on our minds; we were more interested in seeking out a prime spot for a cooling dip in the numerous and private rockpools and spas that abounded above the falls. And so the pattern of our days was set. Start early, walk in the cool, campsite in time for lunch and then a long afternoon of sloth and swims.

Thermarest banana lounges appeared and we settled for some reading in the shade. The quiet time short lived. Brian again, not agitating this time for his afternoon walk but batting ineffectually at the bushflies roosting on his scaly legs. Now, it is nothing unusual for Brian to be flourishing some sort of suppurating bushwalking wound or three, but the weeping dog’s disease spreading over his scaly shanks was an entirely different kettle of fish. Barcoo Rot was my diagnosis. A chronic skin infection right up there with Sandy Blight as an affliction best avoided on long bushwalks. But Nurse Di and Nurse Lyn took a more measured view of his predicament and applied various ungulates and a goodly dose of tough love “Don’t think you can buzz for attention whenever you feel like it tonight, Brian.” Kiwi Ross, a softer touch, took pity on an old walking mate by providing a few metres of fly veil which he rigged up to drape around Brian’s fly-blown legs, noting: “You’d look good in a tutu Brian, but the legs spoil it.”

By late afternoon the Biddlecombe Campsite was full. Our eight, Marion and Charlie and finally four young walkers who blew in late afternoon, having driven from Darwin in the morning and walked in the heat of the afternoon. Mad dogs and Territorians.

Thursday 28 June: Biddlecombe to Crystal Falls: 10.5 kms.

Out in the pre-dawn darkness. To the east a brilliant astronomical display for early risers. Shining closest to the eastern horizon was Aldebaran, brightest star in the constellation Taurus. Then two very bright planets, Venus and Jupiter. But the real gem of the morning sky was an open cluster of stars, The Pleiades or Seven Sisters. The star names are taken from classical mythology and are the seven daughters of Atlas who were pursued by Orion. Zeus, taking pity on them, placed them in the heavens as stars but even there Orion continued his chase. The brightest is called Alcyone who was daughter–in-law to Lucifer, the light-bearer, the star that brings in the day. In fact there are hundreds of giant blue stars in this cluster but only seven are visible to the naked eye.

We were all up, fed and track side by 7.45am closely followed by Marion and Charlie. Here’s the thing about this pair. Both were elderly and Charles had a disability, a problem with his leg. The rocky track and river crossings would have been difficult for Charlie but they were obviously experienced walkers and really dogged. We would swan past, but no sooner had we pulled up for a break in the shade than Marion and Charlie would glide effortlessly past leaving us scrambling to play catch up.

First up was the boots-off crossing of Biddlecombe Cascades, then we followed the track snaking up through increasing rocky terrain; this was the Stone Country. Much of Arnhem Land is made up rocks of the Kombolgie Formation. This formation was first described at Kombolgie Creek a tributary of the South Alligator River. The Kombolgies are mainly sedimentary: sandstones and conglomerates which formed about 1650 million years ago (mya) when huge braided rivers spread at least a one kilometre thickness of the coarse and poorly sorted sediments over the area that we now call Arnhem Land. By 1000 mya the sediments had hardened and compacted to form the

Kombolgie sandstones. We found plenty of examples of ripple marks and cross-bedding testifying to their origins in shallow fluvial or lacustrine environments. The main bedding planes in the Kombolgies are horizontal, reflected in the level surfaces over much of the Arnhem Land Plateau. Interleaved with the sedimentaries are two episodes of volcanic activity, the dark basalts which we saw yesterday as we traversed Seventeen Mile Creek Valley and on the climb up onto the escarpment.

The Jatbula follows in part old droving trails but more significantly it follows the ancient song lines of the Jawoyn. These were landscapes created in a time known as Buwarr, The Dreaming, when the ancestors journeyed across Nitmiluk bringing to life its plants and animals, visiting rock shelters and leaving important artwork. This land was created by Bula, a saltwater being. Bula, accompanied by his two wives, the Ngallenjilenji, journeyed across Nitmiluk creating and naming the landscape as he went. Another dreamtime ancestor was Nagorrko, who told the Jawoyn what skin names they should have and taught them about proper behaviour and marriage relationships. Other creation ancestors included Garrkayn, the brown goshawk; Ngarratj, the white cockatoo; and Barrk, the black wallaroo.

So it wasn’t surprising to find art sites at several of the rock outcrops that we passed on our morning’s travel. The rock art was predominately simple in design: for example, a red ochre hand print, representative of the earliest art work. Other motifs included human stick figures with large headdresses and skirts; larger human figures in red ochre; and highly ornamented figures in motion, the dynamic style. But there was a paucity of animal designs or animals in hunting scenes. These art styles are typical of Pre-Estuarine Art (50,000 – 8,000 years before present); a time when the earth’s climate was cooler and drier and a land bridge existed between Northern Australia and New Guinea.

For the remainder of the morning the trail paralleled the escarpment edge. We cut across six major streamlines, all tributaries of Seventeen Mile Creek and all aligned at roughly 90 degrees to Seventeen Mile, indicative of the strong structural control over the drainage patterns in Nitmiluk. Eons ago, regional crustal tensions cracked and faulted the Kombolgie Sandstones and overlying Cretaceous sediments, often at right angles, forming orthogonal cross joints across the plateau surface. Streams later followed these surface weaknesses and faults leading to the spectacular gorges and rectangular drainage patterns we see today.

Soon after midday we pulled into Crystal Falls, a pokey hot campsite saved only by its proximity to perfect swimming holes and spas. Di and I took to the largest pool immediately while the rest drifted hither and yon in a desultory fashion hoping to unearth a half-way decent tent pad. Trust me, there were none. I moved several times…too hot…too dusty…ant ridden…too close to crocs… before settling on a make-do campsite. The four youngsters drifted in, had a swim then headed off to 17 Mile Falls, ten kilometres hence. Spartans. Late in the afternoon three older walkers sweated it it having walked through from Katherine Gorge in the heat. Clearly shattered. As was our solitude.

A helicopter chuttered in low over the campsite and settled on the emergency helipad set high on the ridge behind us. A genial Kiwi pilot appeared bearing a picnic hamper, all apologies for the intrusion. Two guest appeared. One, a matchy matchy matron from Tassie. Her fellow passenger: unkempt, decked out with dreadies. In fact, badly in need of a major zhooshing up.

In any event they disappeared out to the cascades to enjoy their picnic. In due course our new best friend, the pilot, returned, clutching a barely touched bottle of bubbly and scrumptious left-overs from the hamper. Compliments of his guests. Stand aside Usain Bolt. It was a winner-take-all scramble back to the tents for mugs.

By 4.30 pm our helicopter and its occupants had departed leaving behind a campground of slightly blootered hikers and a tube of perfumed aloe vera ungulate for Brian’s legs. Time for an afternoon explore, a look at the falls. Fortunately, as was often the case, Marion and Charlie had already scouted out the best vantage point: a superb view of the falls and in the other direction, a look down into water foaming through a deep, dark slot canyon.

Friday 29 June: Crystal Falls to 17 Mile Falls via The Amphitheatre: 9.5 kms.

We were now well into our daily walking rhythm. Packed and ready to rock and roll by 7.00 am. Wading across the cascades first, then the 80 metre climb up onto the plateau. Today we would finish our northward march before swinging west towards the Edith River catchment tomorrow. Tonight’s campsite at Seventeen Mile Falls is a titch over the half way point on the Jatbula. This was going to be very easy walking across a stony plateau cut by the occasional dry gully and boggy swamps, still spongy from the wet season.

We were motoring along at a respectable pace when Brian ground to a halt. A blowout in the driver’s side boot. No RACQ service here. So he jury-rigged a temporary fix, thick rubber bands and electrical tape. Interestingly, Ross and a walker from another group also had boot problems. Possibly boot glues drying out in the low humidity. Something to be checked on before extended walking in the Territory.

By mid morning we were traversing burnt out open woodland, a moonscape of rocky pavement covered by ironstone. Since Biddlecombe, on the very highest ridges at about 300 metres we found nodules and cappings of ironstone or ferricrete. These nodules were formed by the laterisation of the Cretaceous sandstones which overlie the Kombolgie Formation. During the Tertiary starting 70 million years ago, much of northern Australia was subjected to a humid tropical climatic regime. Under high rainfall conditions hydrated oxides of iron and aluminium accumulate steadily in surface rocks as other minerals are leached out, so that a hard iron rich crust develops.

The track led out to the escarpment’s edge where we pulled up at a horse-shoe ring of cliffs, The Amphitheatre. Below in its basin was a cool clear stream trickling under the dappled shade of a pocket of sandstone monsoonal rainforest.

The rainforest canopy is dominated by Native Apple Tree (Syzygium spp.), Leichhardt Tree (Nauclea orientalis), Carpentaria Palm (Carpentaria acuminata), Native Nutmeg (Myristica insipida) and the White Paperbark (Melaleuca leucadendra). Nestled in their shade were numerous ferns and flowering shrubs like Melastoma polyanthum. These pockets are considered to be relict plant communities from a time when much of the Top End was covered by rainforest.

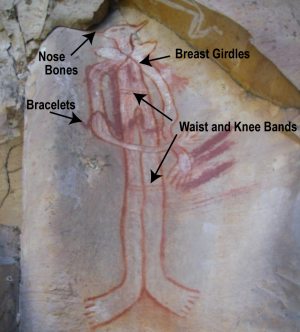

There are said to be 420 rock art sites in Nitmiluk, but one of the best is along the walls of The Amphitheatre. Three main panels display a mixture of Pre-Estuarine and Estuarine Art styles. Early designs of hand stencils, emus, emu tracks, long-necked turtles mixed with later art styles from the Estuarine Period (8000 to 2000 BP). These included Yam Figure Style, X-ray art, and most spectacularly, a large humanoid figure of a Jawoyn Lady wearing nose bones, breast girdles, bracelets, waist and knee bands.

From the coolth of The Amphitheatre it was onward across the baking savannah, at least 32°C and hardly a breath of wind for the three kilometres to our campsite. Interestingly, despite the high temperatures I heard no cicadas for most of the trip. Perhaps the humidity was too low (generally below 20%) for hatching. The track quickly wound out to another lookout, this time for a view of Seventeen Mile Falls, the highest single-drop fall in Nitmiluk. Half an hour later we trailed into Hades, our godforsaken burnt-out campsite above the falls. Still, with an excellent rockpool just below the campsite, one was actually in heaven. Lunch in the shade, sprawled out on a rock shelf, washing of clothes, swims, and more swims. A whole afternoon of general lethargy stretched ahead. Lying on the rocks, books in hand. Ross and Linda engrossed in Michener’s Hawaii; Di, Lyn and I delving into Jodi Picout’s 19 minutes; Sally lounging in the water; Brian still fussing away over his bodgy boots and Don, an afternoon of rockwalling his tent site in an effort to keep out the passing campground riff-raff.

Late in the afternoon Marion and Charlie again slipped silently away from the campsite, off on another of their evening rambles. I waited and watched. Sure enough, they re-appeared on a rocky outcrop high above the campsite, overlooking the falls. I knew I could count on them to ferret out the ideal eyrie for a look at the falls and down Seventeen Mile Creek. We formed up and wandered up to join them.

Another warmish evening. No campfires allowed, but we sat around chewing the fat while the moon rose. Too bad about the moonshine, for it is said that the glow of the lights of Katherine are visible to the south west.

Saturday 30 June: 17 Mile Falls to Sandy Pool Camp: 16.5 kms.

Our longest day, sixteen kilometres. Sunrise came soon after 7.00 am, a blood-red sun shrouded in a curtain of smoke haze. The iconic Top End sunrise. Fire is an integral part of Nitmiluk’s landscapes and its aboriginal custodians and Parks staff burn off during Malaparr, the early dry season from May to June. It is then that the grasses still contain a little moisture and the burn-off will be low intensity and will generally falter at watercourses, swamps and rock pavement. For much of our walk we encountered patchworks of burnt and unburnt areas, presumably to suppress the possibility of a major wildfire along the track and at campsites.

Our last hours on the stony plateau country, again travelling on the high laterised surfaces. We were now on the drainage divide between the Edith River and Seventeen Mile Creek. As always termite mounds abounded, one of the most ubiquitous features of the Northern Territory landscapes. Right up there with the favourite Top End images of crocs, waterfalls and red sunsets. Here the surrounding termite mounds took on a distinctly reddish tinge in contrast to the lighter coloured mounds we encountered elsewhere. Wherever there is grass in the Top End, there are termites, which is everywhere.

During the long dry season it is so dry that other important recyclers like earthworms cannot survive. So termites are known as the ‘earthworms of the tropics’. The termite is an ancient order of insect which has been ranging the earth for as long as crocs, some 30 million years. Its nearest relative is the cockroach, not ants. Hence the name ‘white ant’ is a misnomer. Most termites have simple appetites, content to graze on dead grass, seeds and wood, converting cellulose directly into glucose for energy. But the most primitive group, the Masto termite, endemic to Australia, is not so particular and has been found happily munching through old car battery cases, bitumen highways, PVC, lead sheathing on Telstra cables and demolishing a three bedroom house in a single 10 week feeding frenzy; much like our pre-trip poolside breakfasters.

Our route took us westwards off the stone country into an unnamed swampy headwater tributary of the Edith River. The Edith River was named by William McMinn in 1871 during the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line. Lady Edith Fergusson was the wife of the South Australian Governor, Sir James Fergusson.

Here was a different landscape, a mosaic of swampy grasslands, riverine forest and open woodlands. The vegetation around us marked the change, now pandanus, melaleucas, banksias and grevilleas. We had reached the Edith River Soaks, a landmark for drovers which signalled that they had finally left behind the harsh stone country for the succulent grasses of the Edith River floodplain. Some three hours of early morning hard yakka paid off as we cruised into the Edith River Crossing and a well-earned dip. Here the Jatbula shifts to the western bank all the way downstream to Leliyn. A quick feed and we took off on the six kilometre hop to Sandy Camp Pool hoping to beat the heat as my pack thermometer was fast cranking up, a mid-morning 32°C. Sandy Camp is one of the highlights of the walk, easily the most picturesque of Jatbula’s pools. The campsite nestled on a sandy beach under shady trees. A few metres from my tent I launched into the deep clear waters of Sandy Camp Pool. Fantastic.

Sunday 1 July: Sandy Camp Pool to Sweetwater: 10 kms.

Awake with the pre-dawn howling of dingoes, another clear piccaninny dawn for our penultimate day. Trackside by 7.45 am but a slight delay as we bumbled hither and yon looking for those nifty blue Jatbula triangles. Eventually someone got smart and realized that if we headed downstream we would soon find the trail. Just so. Much of the morning’s walk is through dense swathes of high grassland. I’d hate to walk this stuff without the well-defined pad that we were following. Above our heads, old flood debris had caught in the scattered shrubs and trees, obviously not a good place to be during the late wet season. We puttered along in the balmy tropical morning and just before

mid-day we rounded up onto a low river bluff overlooking the Sweetwater. Below, those toads of the trail… day trippers. Four of the cheeky blighters frolicking in the cascades above Sweetwater Pool. Our throughwalking solitude was over. Sweetwater is easily accessible to day walkers so we could expect to see legions on the move in our final 24 hours on the track.

A final lux afternoon of swims, rambles around the Sweetwater, botanising, checking out the sandstone ripple marks, more reading and brew-ups. Having exhausted these possibilities for the productive use of my time, I turned my attention to niggling Don about his ongoing refusal to buy a Thermarest banana lounge. After many years of badgering he finally caved in and agreed to try one out and grudgingly conceded it was “…comfortable”. But stubbornly unconvinced. Thence to Brian, whose beloved ancient hike tent stood agape where several zips now refused to close, its flaps cobbled together with a network of safety pins. “It’ll see me out.” With dingoes serenading in the near distance we drifted off to our beds, but not before peering into the dark then pulling our boots into our tents and finally zipping the doors firmly closed. We left Brian to his fate.

Monday 2 July: Sweetwater to Leliyn: 4 kms.

A cool 11°C start for our final two hours on the track, Leliyn being a mere four kilometres away, passing numerous rapids and the Longhole on our way through. We were now a pretty subdued bunch. After such an outstanding trip I wouldn’t have minded a few more days on the track. All good things come to an end and we pulled into the well-appointed Leliyn campground soon after 10.00 am. But we quickly perked up when the campground manager threw open the chuck wagon and we tucked into a truck load of pies, sausage rolls, potato chips, chocolates and soft drinks. An afternoon of general slacking around and desultory walks completed a memorable six days of walking with great companions and excellent leadership provided by Ross and co- organizer Linda.

Related Articles:

A. Davison The Jatbula Trail Wild Magazine Issue 110

J. Byrne Exploring the Jatbula Trail Aust Geog May 2011