After our previous day’s walking on the Snowies Alpine Walk from Charlotte Pass Village to Perisher via Porcupine Rocks, we were keen to check out another new section. This time we settled on the new nine kilometre walk from Charlotte Pass to Guthega village. A top day beckoned. Clear skies, maximums hovering around 21o C and an alpine ramble with my walking friends Joe, Chris, Neralie and Garry.

by Glenn Burns

The BOM had issued a heatwave warning in its Snowy Mountains forecast. But for this quintet of Queenslanders the threatened 21o C maximum was just so. Not too hot, not too cold.

Snowies Alpine Walk

In 2018 construction started on the Snowies Alpine Walk. The NSW Government boasted it would deliver ‘ a world-class, multi-day walk across the alpine roof of Australia in Kosciuszko National Park.’

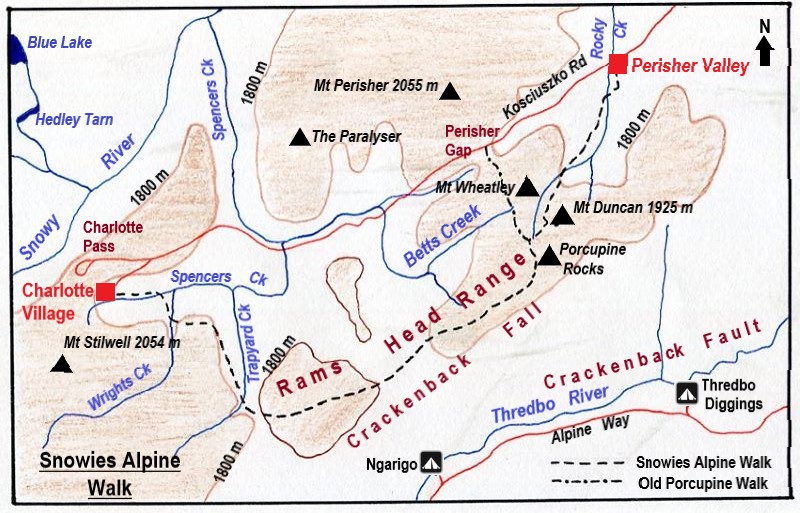

This 55 kilometre, 4 day walk, on Ngarigo Country, connects the existing Mt Kosciuszko-Main Range walk with three new sections. Namely, Charlotte Pass to Guthega Village; Charlotte Pass Village to Perisher Village via Porcupine Rocks and, as of 2024, the still incomplete section from Perisher Village to Bullocks Flat in the Thredbo River Valley.

After a top day of alpine walking yesterday from Charlotte Pass to Perisher, life on the track was on the up and up. An uneventful drive, with Joe at the wheel, from our digs at Sawpit Creek, delivered us to Charlotte Pass (1840 m).

Bang into an unexpectedly biting wind. Someone had neglected to clock the forecasted 50 kph wind gusts. So with the wind chill effect, the ambient temperature was pretty cold. And this was mid-summer, Australia. As my old walking pal Brian was apt to say: ‘strong enough to blow a brown dog off its chain’. We pulled on an extra layer.

Pleistocene Glaciation in Kosciuszko National Park

If you had been standing at this very spot some 60,000 years ago, in the frozen depths of the last Pleistocene ice age, the scene in front of you would have been vastly different.

You would have gazed across a panorama of snow and ice. Rivers of ice poured out from ice-filled glacial bowls on the south east flanks of Mt Lee, Mt Clarke, Carruthers Peak, and Mt Twynam. The current valleys of Club Lake Creek, Blue Lake Creek, Twynam Creek would be brimming with glacial ice grinding bedrock to a pulp on its way to join the major valley glacier in the Snowy River.

In fact, it is possible that your perch at Charlotte Pass would have been covered by a mass of abrading Snowy River glacial ice pushing over this interfluve into the neighbouring Spencers Creek valley. Or so some geologists hypothesise.

Back then temperatures would have been much colder. The minimum temperature today was 12o C. 17,000 years ago it would have been at least 5 to 8o C lower.

In Kosciuszko there is evidence of at least two distinct glaciations. The Early and Late Kosciuszko glaciations. The Early Kosciuszko Glaciation consisted of a single major advance at approximately 60, 000 years ago called the Snowy River Advance. This was the most extensive advance with later advances less extensive.

Geologists tell us that the Snowy River glacier probably extended as far downstream as Illawong Hut. Possibly further. There is evidence of glacial debris downsteam at Island Bend, discovered during surveys for the Snowy Mountain Scheme.

The Late Kosciuszko glaciation consisted of three smaller glacier advances, starting about 32,00 years ago: Hedley Tarn Advance (32,000 years ago), Blue Lake Advance (19,000 years ago) and Mt Twynam Advance (17,000 years ago).

The systematic search for evidence of glaciation in Kosciuszko got seriously under way in 1901. A scientific party of Professor T.W. Edgeworth David (geologist), Richard Helms (zoologist and botanist), E.F. Pittman , and F.B. Guthrie (Professor of Chemistry) found incontrovertible evidence of the action of glacial erosion and deposition:

- striated rocks and boulders

- erratics

- terminal and lateral moraines

- roches moutonnees

- cirques

- tarns

- glacial polishing of rock surfaces

- truncated spurs

- U-shaped valleys

- abraded interfluves

The Kosciuszko Plateau has been now been free of of glaciers for about 15,000 years. In addition to the glacial landforms mentioned above, the observant bushwalker can find ample evidence of periglacial landforms over much of the higher country. Some easily identified of these landforms include blockstreams, solifluction terraces and thermokarst ponds.

Meanwhile, back in the Anthropocene, the Snowies Alpine Walk (SAW) from Charlotte Pass initially heads downhill on the paved NPWS vehicular track towards the Snowy River. Some 500 metres of descent will deliver you to a junction and noticeboard trumpeting the start of the walk to Guthega village. We executed a hard right onto the SAW path.

Map of Snowies Alpine Walk: Charlotte Pass to Guthega Village.

Here the SAW parallels the Snowy River on its eastern bank, winding around Guthrie Ridge on the 1700 m contour before dropping to Spencers Creek and the Snowy River at Illawong Hut. The final part of the day’s walk picks up the old Illawong-Guthega bushwalker’s pad to fetch up at Guthega Village, some nine kilometres from Charlotte Pass.

Back in the Day… 2009… Guthrie Ridge.

But, back in the day, in 2009, a 17 kilometre walk from our camp on Strzelecki Creek under The Sentinel to Charlotte Pass thence to Illawong Hut via Guthrie Ridge was more of a challenge. We set off with a brilliant off-track alpine ramble from Strzelecki Creek to Charlotte Pass via Carruthers Peak, Mt Northcote, Mt Clarke and the Snowy River Crossing.

Once at Charlotte Pass we swung off-track again to climb Mt Guthrie (1920 m). The usual suspect had cooked up this feral route that followed the spine of Guthrie Ridge (1900 m) and then descended to an overnight bivvi at the junction of Twynam Creek and the Snowy River. Close to Illawong Hut.

Mt Guthrie and Guthrie Ridge were named by Richard Helms for his friend F.B. Guthrie, Professor of Chemistry.

My peak bagging companion had hinted at another exceptional alpine stroll to cap off what had been, so far, a matchless day of hiking. A mere two and a half kilometres or a one hour leisurely amble along the spine of Guthrie Ridge would deliver us to our campsite on the junction of Snowy River and Twynam Creek. Fun times.

Mid afternoon, on a steep mountainside, high above the valley floor three beleaguered peak baggers pushed wearily through the tangle of granite boulders and scratchy mountain peppers, Kunzeas, Epacris and snow gums that lay between them and the day’s end. Route wise, a bad call.

But I was resigned to this stuff. Situation normal when walking with my bush-bashing, peak bagging buddy Brian. He claimed it was just the price we had to pay for a very satisfying and bludgy morning’s walk. Finally, we staggered in just on dusk. The campsite made it all worthwhile. We set up on a springy snow grass ledge… lulled to sleep by the riffling Snowy River. All was well in my little slice of bushwalking paradise and all is forgiven Brian.

The new Snowies Alpine Walk.

After mulling over this previous cross country experience I gave thanks for the newly minted super SAW highway. Cortan steel elevated boardwalks, rock-armoured track surfaces and dry boots compliments of a high suspension bridge over Spencers Creek. A speedier passage than taking that infernal high road along Guthrie Ridge. But nowhere near as interesting.

The track took us initially over another of those eyesore Cortan steel boardwalks much favoured in Kosciuszko National Park. But I admit they do an excellent job of protecting the low heath and snow grasses below.

Eventually the track leaves the low heath and climbs on its granite pavement ever upward through snow gum woodland. As did Garry. Left us, that is. We found him, as I expected, propped on a log in a bower of snow gums. The ideal morning tea stop.

Snow gum woodland, invariably, is clothed in a dense scrubby understorey of beastly spikey undergrowth like Bossiaea, Epacris, Hakea, Grevillea, Oxylobium, and Kunzea . Here’s where those weird knee-length canvas gaiter things worn by Australian bushwalkers are a brilliant piece of kit.

The low growing snow gum woodland is found above 1500 metres and is dominated by snow gums or white sallee ( Eucalyptus pauciflora).

The snow gum zone is found extending down to the lower levels of winter snowfall and is the only tree to grow above 1500 metres. Above this woodland zone the landscape transitions suddenly into the true alpine zone of heathland, grassland and bogs.

The undergrowth is called heath and can be waist-high with tough whippy branches to withstand the weight of snow (and, hopefully, bushwalkers) without breaking. Throw in the odd torpid highland copperhead and pit-fall traps of wombat and bunny burrows and hiking through this scrub quickly losses its appeal.

Fortunately, the new super SAW highway saved us from having to thrash through that stuff.

Much of the SAW walk parallels the Snowy River which flows NNE downstream towards Guthega Pondage. It is joined on its western bank by the south east flowing drainage lines of Blue Lake Creek, Twynams Creek and Pounds Creek.

These creeks have their headwaters along the highest parts of Australia’s Great Dividing Range: Carruthers Peak (2010 m), Mt Twynam (2196 m), Mt Anton ( 2010 m) and Mt Anderson (1997 m). The Main Range peaks all visible from this section of the SAW.

Today’s walk provided expansive and unimpeded views down the nearly straight Snowy River Valley. Its side slopes planed back by late Pleistocene valley glaciers. Glacial valleys all over the world typically exhibit these truncated spurs and U shaped valleys.

Some 4.5 kilometres after the track entrance our path left the snow gum woodland and descended across low heath covering a gently rounded spur at the intersection of the Snowy River and Spencers Creek. An abraded spur, ground down during the Pleistocene by the Snowy River and Spencers Creek valley glaciers.

Joe and I caught up Chris and Neralie just short of the Spencers Creek suspension bridge. They were magging with two walkers travelling in the reverse direction. Uphill to Charlotte Pass. I’m not sure of the rationale for doing this section uphill, but many people do. Meanwhile, Garry was last seen as a distant speck beetling toward Illawong Hut.

The SAW track builders had thoughtfully provided a nifty suspension bridge consisting of a steel mesh plank and handrails to usher walkers safely across Spencers Creek. Built in 2021 it is said to be, in terms of its location, at 1627 metres of altitude, the highest suspension bridge in Australia .

Meanwhile Garry had escaped the wind by taking refuge at the side of the hut. Just don’t turn up here in a serious blizzard. You will find the inn door locked, as we did. An unusual arrangement for high country shelters. But this is because Illawong is the only private lodge outside the main ski resorts.

But, to be fair, the illustrous Illawong Ski Tourers have thoughtfully provided a sealed crawl space for midgets under the hut for just such an emergency. And, they have thrown in as a goodwill gesture, a snow shovel to dig yourself out or in. Once out of your blizzard, don’t try to sit up. The upside is that you are safe and don’t have to share the under floor space with assorted snakes, wombats and other creepy-crawlies.

Illawong Hut

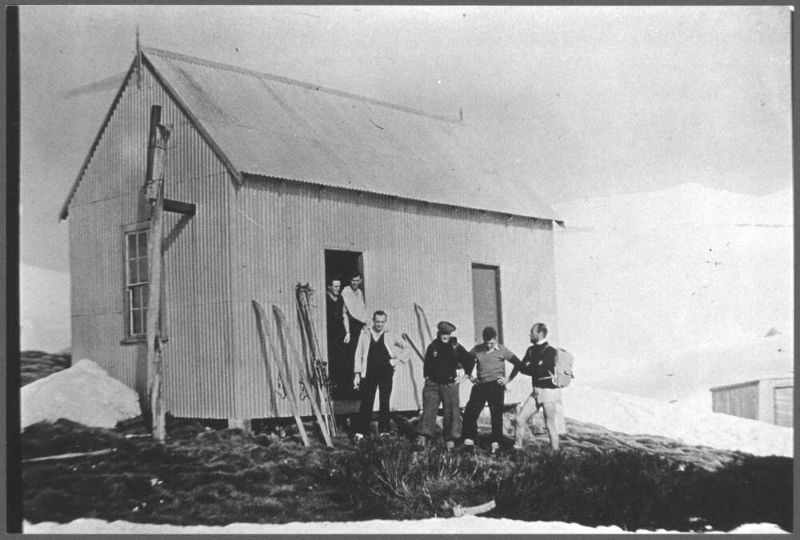

Illawong, also known as Pounds Creek Hut and Tin Hut No1, was constructed in the summer of 1926-1927 as a shelter hut. Illawong is said to mean ‘view of the water’. A basic two roomer/four bunks, it was built by the NSW Tourist Board to assist Dr Herbert Schlink in his first Kiandra to Kosciuszko ski crossing during the winter of 1927.

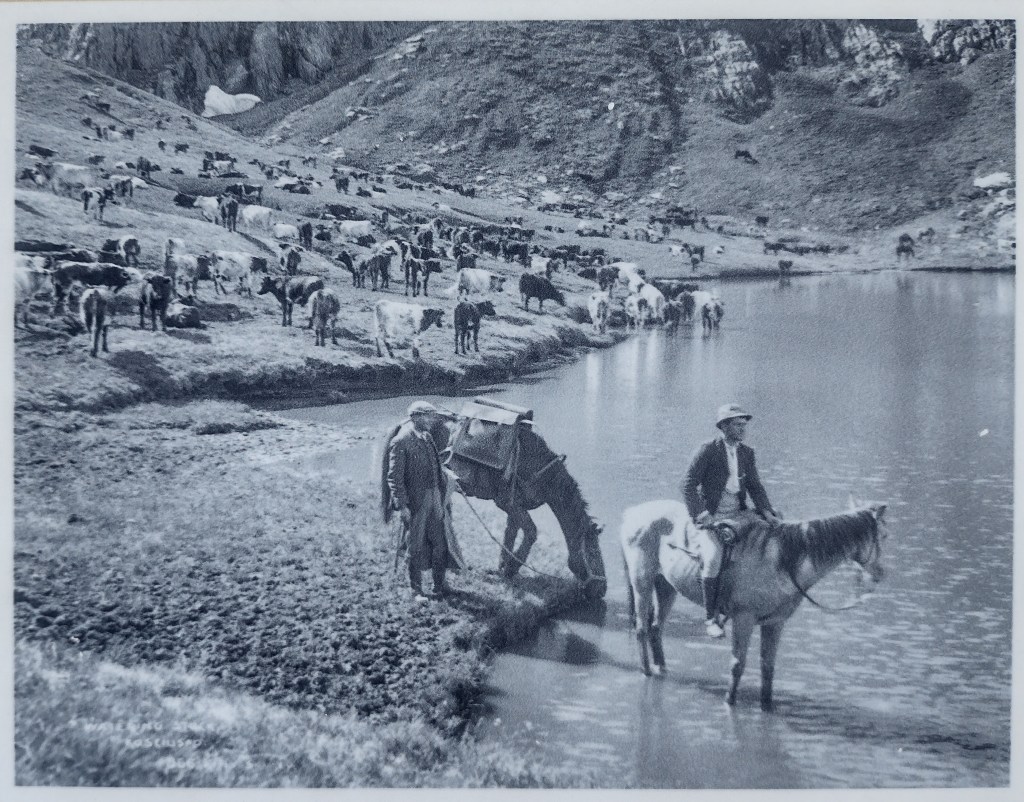

After construction it was used for early ski touring, summer bushwalking and by mountain cattlemen. At the time only two other buildings existed in the high country: Betts Camp and Kosciusko Hotel.

In 1955, John Turner of the Ski Tourers Association brewed up a plan to convert Pounds Creek Hut into a ski lodge. A year later, in 1956, the Kosciuszko State Trust gave permission for the hut to be extended to become a private ski lodge managed by Illawong Ski Tourers.

The conversion was a bit of mission for lodge members. No helicopter lifts in those days. All materials and food supplies had to carried in. Though some ingenious work-arounds were dreamt up. Klaus Hueneke in his first-rate tome: Huts of the High Country provides this description:

” Over the next two years members, friends and passersby spent endless summer days and occasional premature wintry ones carrying, rowing, pushing and dragging materials to site. “

And this:

” Rowing the materials up Guthega Dam was a new twist to mountain transportation and not without incident… boat trips took on ice floes, wind driven sleet and polar wombats! The final leg was considerably aided by a sled and the muscle power of Mick, a horse from the Chalet. Unfortunately he had only two speeds – stop and run like hell. “

Those enterprising Illawongians weren’t finished yet. Over the years the Lodge was spruced up with a septic tank, electric lighting, a gas cooker, a refrigerator, a hot water service, decent mattresses, carpets and a phone. A veritable home away from home. My membership application is in the mail.

Members also designed and built the flying fox over Farm Creek and the suspension bridge over the often raging Snowy River. For this latter feat all skiers and bushwalkers wanting to access the Main Range should give them fulsome thanks. Two earlier bridges had been swept away before a decent one was installed in 1971. The final version was designed and built by one Tim Lamble and assembled with the help of the NPWS helicopter.

Tim, incidently, is also the author of my favourite piece of cartographic art: the Mt Jagungal and The Brassy Mountains 1:31680 map.

Illawong Hut has been placed on the National Heritage Register, the National Trust (NSW) Register and NPWS Historic Places Register. Its NPWS citation reads:

” Illawong Hut is one of the most historically significant huts in the park, being a rare remnant of early 20th century NSW Government Tourist Bureau efforts to promote alpine tourist recreational activities.”

For good measure the Farm Creek flying fox and the Snowy River suspension bridge are also on the register.

With little over two kilometres to Guthega my friends had scarpered in a cloud of dust. The upgraded SAW track follows the old bushwalking pad between Illawong and Guthega. It skirts around the southern bank of Guthega Pondage. This pondage, a tunnel and Guthega (Munyang) hydro power station were built as part of the Snowy Mountains Scheme in the early 1950s.

Munyang (Guthega) Hydro Power Project

This Munyang (Guthega) project area is the start of many of my favourite walks in Kosciuszko.

And it is also the start of the first major project of the Snowy Mountains Scheme in 1951. The tender was awarded to a Norwegian firm, Ingenior F. Selmer. A serious player in global dam and hydro construction. The bulk of the workers were Norwegians (450, mainly labourers) from the rural areas of the Arctic Circle.

On the 21 February 1955 , only a few weeks behind schedule, electricity flowed from Munyang.

The word Munyang or Muniong derives from local aboriginal people. When camped on the Eucumbene Valley, they would point to the snow covered Main Range and repeat the word ‘Munyang’ or ‘Muniong’ . Said to mean ‘big’ or ‘high mountain’. Also ‘big white mountain’.

If you want to read more about the fascinating people and places of the Snowy Mountains Scheme, I can highly recommend Siobhan McHugh’s: ‘The Snowy, a History.‘

Nearing the end of our walk, the SAW crosses Farm Creek via a metal bridge then climbs to Guthega Village. No need to risk life and limb on the the rusty old flying fox still there. Fortunately, it has been padlocked by some kill-joy to discourage thrill seekers like my walking companions.

At the still to be completed track exit, rangers were busy fiddling around sorting out signage. Here we had views over the waters of Guthega Pondage, the dam wall and the intake for the tunnel to the top of the Munyang penstocks.

Guthega Ski Village or Little Norway

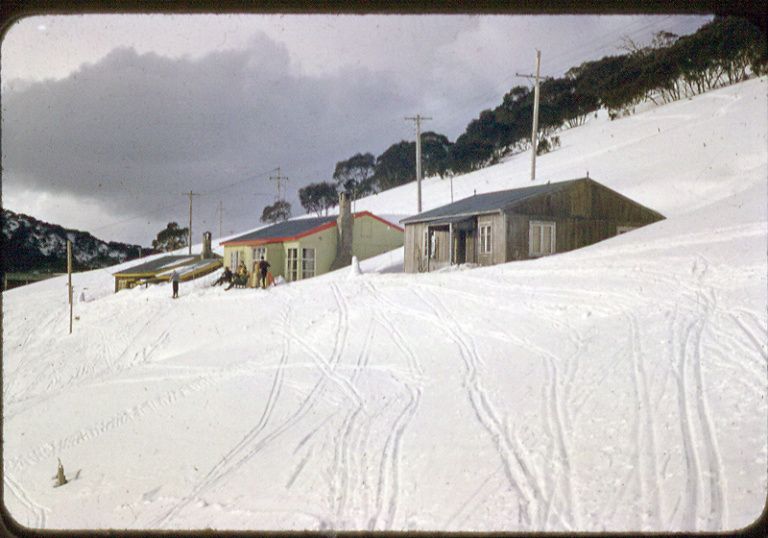

Guthega village did not exist before 1950. The only building in the area was our old friend Illawong Hut. In 1951 when the Norwegian company Selmer started construction on the first major project of the Snowy Mountains Scheme , their construction camp became known as ‘Little Norway’ as it housed the largest number of Norwegians living outside of Norway at the time.

When Selmer returned to Norway in 1954, at the end of their contract, they took most of their construction camp with them, leaving just three huts. These huts kick-started the modern day Guthega Ski Resort.

The huts were scooped up for peanuts in 1955 by SMA Cooma Ski Club, YMCA Canberra Ski Club and Sydney University Ski Club. The village now sports private lodges, a restaurant and bar, commercial resort accommodation and various tow knick-knacks to ferry skiers to the top of their runs.

Guthega serves as a winter base for downhill skiing, cross country skiers, snow-shoers and snow-boarders. The alpha adventurers head for Blue Lake to try out their ice climbing skills. But in summer, Guthega is pretty much dead. A ghost resort. Hopefully, this will change given the number of walkers I saw on the track.

It was now two hours past our lunch hour. A familiar pattern developing here, much to the chagrin of my fellow walkers. We found Garry’s vehicle, wheels still attached, piled in and headed for nearby Island Bend Campground on the Snowy River for a belated feed.

The campground was once the site of a construction village for the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

We ducked into a pleasant little nook with a picnic table and some soft grass for a post-prandial kip. All in all, a top day of alpine hiking with my walking companions, Joe, Chris, Neralie and Garry.

I had many more days of alpine adventures for my fellow Kosciuszkians. God bless their little walking boots. Maybe not so little.