by Glenn Burns

Mt Stilwell (2054 m) is, for me, probably one of the best short walks in Kosciuszko National Park. At only 1.8 kilometres from Charlotte Pass, on a clear day, it gives unsurpassed views of the Snowy River valley, the peaks of the Main Range and in season, brilliant wildflower displays.

A bonus of the Stilwell hike is that it is ignored by most of the walking fraternity. Out of the summer school holiday period you will have this part of the park to yourself. It’s Kossie or bust for most hikers, trail runners and, in recent years, flocks of mountain bikers, all heading for Rawsons Pass and Mt Kosciuszko.

But for those of us with more modest ambitions and time to spare, one can have a thoroughly enjoyable ramble to the top of Stilwell. And, should you have time, you can explore the extensive alpine meadows of upper Wrights Creek and Merritts Creek, duck across to nearby Little Stilwell, check out the ruins of the Stilwell Restaurant (aka the Ramshead Restaurant) or maybe head off along Kangaroo Ridge. Endless possibilities for the enterprising bushwalker.

Our fifteen kilometre summer ramble would take us to Stilwell Trig, thence off-track, contouring along the eastern flanks of Kangaroo Ridge. Followed by a gentle overland descent towards the Merritts Creek crossing on the Summit Walk from Charlotte Pass to Mt Kosciuszko. From here it’s a short hop over the Snowy River then uphill to Seamans Hut. The return trip is downhill along the Summit Walk to Charlotte Pass.

Map showing Mt Stilwell to Seamans Hut hike

And so, soon after 9 am on a blustery summer’s day, I set off with my ever keen walking companions, Neralie, Chris, Garry and Joe. Stilwell bound. Another cool 10O C but with the monotonously regular north-westerly idling along. Ideal walking conditions in my book.

From Charlotte Pass the track climbs through a belt of snow gum woodland to the rusting relics of Australia’s first mechanical ski ‘hoist’.

The Pulpit Ski Hoist

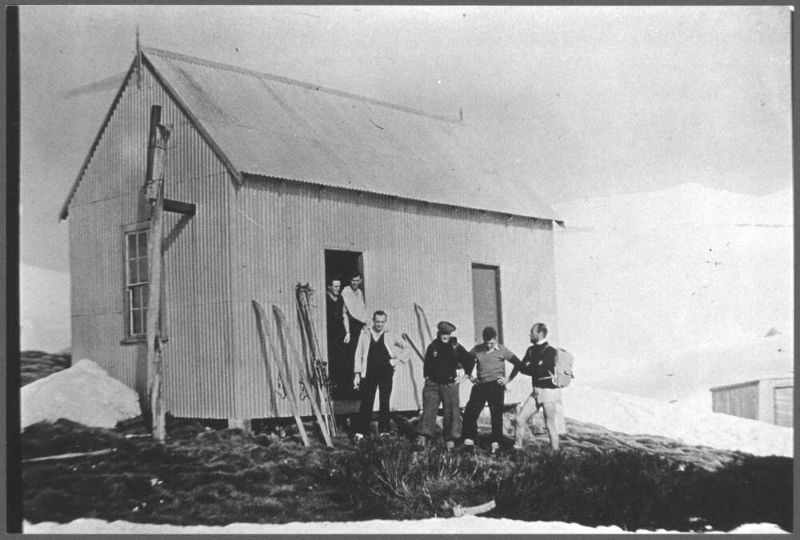

In 1938, the New South Wales Government Tourist Board (NSWGTB) built Australia’s first long ski tow from Charlotte Village to Kangaroo Ridge. It resembled a modern T-bar with steel cables suspended from wooden posts.

Way back in 1937-1938 it was a difficult build. The long poles for seven A frame towers were cut in Wilsons Valley and had to be carted and then assembled on a very steep slope. The wooden towers supported the heavy steel cable to which were attached non-OHS compliant J-bars for the skiers to hang on to.

But it was a very welcome addition to Australia’s skiing scene. Although it had a few issues. Rick Walkom in his wonderful book ‘Skiing off The Roof’ has this description:

‘Skiers experienced plenty of lengthy stoppages. The hangers travelled at no more than walking pace, and the build up of ice often caused derailments. Sometimes the J-bars would get caught up in the rocks or, worse still, the heavy hangers would fall off the cable. A veritable army of skiers was needed to lift the cable back onto the pulleys.’ All part of the fun.

Some 600 metres further on is the Charlotte Village to Kangaroo Ridge Triple Chairlift, which does not operate in summer. Here, at 1920 metres, is a Cortan steel lookout with unimpeded views to the Main Range and Mt Stilwell, capped by its trig tower. An information board acknowledges indigenous links to Kosciuszko:

‘The local rainmaker, Dyilligamberra, represents all the rain, snow and water from these mountains to the sea. His relatives make wind and cloud. They are very powerful, so we show our respect by going quietly in the mountains.’ Rod Mason. Aboriginal Education Officer.

The lookout platform provides a brilliant skyline view of the Main Range. On a clear day like this, all the high peaks are visible and you can identify them from the labelled panorama on the information board. From east to west (L to R): North Rams Head, Mt Kosciuszko, Mt Clarke, Mt Townsend, Mt Lee, Carruthers Peak, Mt Twynam, Mt Anton and Mt Tate. A Who’s Who of Australia’s highest peaks.

But the Stilwell summit beckoned. We were now in Australia’s true alpine zone. In Kosciuszko this equates to about 1850 metres ASL. Here the average summer temperatures are less than 10 C, too cold for even hardy snow gums to survive. Hence snow gum woodland is replaced by tall alpine herbfield.

Tall alpine herbfield

The tall alpine herbfields are the most extensive of all Kosciuszko’s alpine plant communities and are found on well-drained and deeper soils. These herbfields occur on a variety of bedrock types, suggesting that lithology has a negligible influence on location. Here, the bedrock is Mowambah granodiorite which erodes to form sandy and well-drained soils. Obviously perfect for wildflower meadows.

This plant community is the most diverse of all the alpine vegetation types in terms of number of species. Showy wildflowers grow in a matrix of snow grasses (Poa caespitosa) and sedges (Carex sp). Technically, it is an association dominated by the genera Celmisia (daisies) and Poa.

As we were walking in late summer the wildflowers were well past their prime. Later the same year in mid-December the display was spectacular.

Here is my mid-December list: silver snow daisy (Celmisia astelifolia), Australian bluebells (Wahlenbergia spp), star buttercups (Ranunculus spp), bidgee widgee (Acaena anserinifolia), Australian gentians (Gentiana spp), eyebrights (Euphrasia collina spp), billy buttons (Craspedia uniflora), spoon daisy (Brachyscome sp), yellow Kunzea (Kunzea muelleri), tall rice-flower (Pimelea ligustrina), alpine mint-bush (Prostanthera sp), alpine Stackhousia (Stackhousia pulvinaris), mountain celery (Aciphylla glacialis) trigger plant (Stylidium montanum), purple alpine Hovea (Hovea montana), and violets (Viola betonicifolia).

Alpine wildflower guide for your rucksack

A bushwalkers’ pad climbs up through these meadows and is very exposed. It was windy, the UV index was off the scale but the walking was brilliant. We crossed meadows, seepages and weaved in and out of the outcropping granodiorite boulders.

Xenoliths

If you keep your eyes open, you will see large patches of foreign rock or minerals embedded in the granodiorite. These are Xenoliths. There is some argumentation over the origins of Xenoliths (Foreign Rock). At its simplest, it is thought they are fragments of existing country rock caught in the molten magma as it cools.

As usual, I couldn’t gee up much interest in Xenolith spotting, so we pushed on to the summit. It is topped by a trig tower atop a spine of heavily frost-shattered rock. With the summit photo shoot completed, we retreated to the lee of the summit. To a pleasant sunny spot that Garry and Neralie had secured for our morning tea, out of the wind.

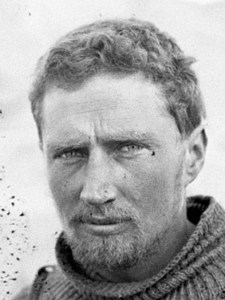

Frank Leslie Stillwell

It is likely that Mt Stilwell was named after Frank Leslie Stillwell (1888 – 1963).

Stillwell (note spelling shift) was an Australian geologist and Antarctic Expeditioner (1911-1914). He served under the famous Douglas Mawson. Stillwell’s later career took him to the mining provinces of Broken Hill and Kalgoorlie.

On the eastern side of Mt Stilwell, just below the summit, if you look carefully you should be able to find a massive vein of milky quartz embedded in a boulder of Mowambah granodiorite. Milky quartz is a very common mineral. I have sat here many times for morning tea, but 2024 was the first time I clocked this huge outcrop.

Also nearby, if you peer hard enough off to the south east, there are the ruins of Top Station or Ramshead Restaurant. It is located near a biggish outcrop on the Rams Head range about 1.5 kilometres across the marshy valley of Wrights Creek.

The World’s Longest Chairlift

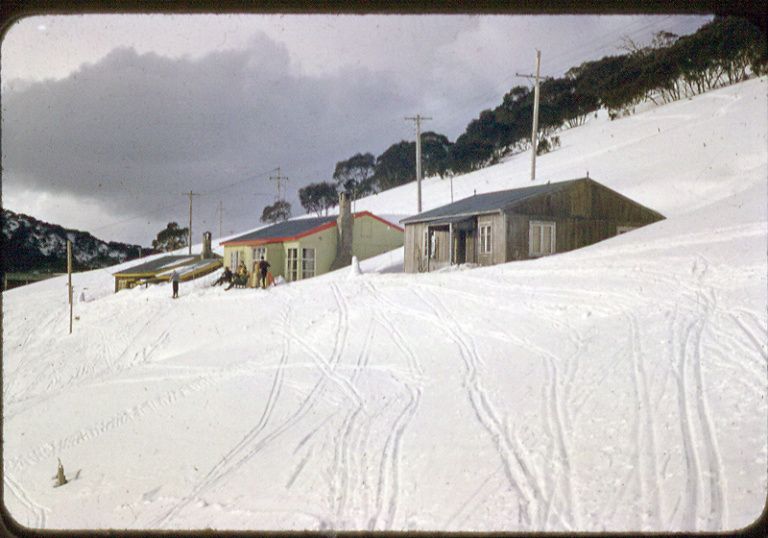

A restaurant and lift transfer station were built at the highest point on the line of the Thredbo valley to Charlotte Village chairlift. Purportedly, the ‘World’s Longest Chairlift’. It was built in 1964-1965 at the junction of the two chairlifts. One from the Thredbo valley and the other from Charlotte Village.

Building the chairlift was a major engineering feat. Work started in 1963 on a ‘Sedan’ style chairlift moving 350 skiers per hour in both directions. The sedan seat was enclosed by a fibreglass cupola.

There were high hopes for the popularity of the chairlift which was to glide five kilometres over the freezing roof of Australia. As a bonus, punters could drop in for a feed at the Stilwell/Ramshead Restaurant. At 2057 metres touted to be the highest in Australia.

Rick Walkon in ‘Skiing off the Roof’ has this description of the chairlift’s history:

‘The chairlift was a disaster from the start.

The Snow gods wasted no time in showing disdain for the sea level engineers. With the first snow falls in 1964, a variety of design faults became glaringly obvious… Incessant strong winds on an extremely exposed plateau hit the chairs at right angles, causing them to swing violently and nearly collide with towers.

More often than not, a busload of sightseers complete with high-heeled shoes, cameras and bags ended up dangling in icy winds awaiting rescue. Inevitably a few passengers fell out of the chairs’.

Apparently, a blizzard started in July 1964 and lasted 31 days. At the time wind gauges registered 180 kph and eventually blew away. Chairs were ripped from the cables and towers buckled. More blizzards followed.

Understandably, rumours of frozen corpses arriving at the Top Station did not engender confidence in a ride on the World’s Longest Chairlift. Suffice to say, the chairlift closed after only two seasons.

For those of you keen about skiing and the history of skiing in Australia and Charlotte Pass in particular, look no further. Rick Walkom’s ‘Skiing off The Roof‘ is jammed packed with facts, anecdotes and hundreds of historical photographs. This book is a treasure.

But we were on a different mission. After a bite to eat, we headed off, travelling south west, paralleling the summit skyline of Kangaroo Ridge on the 2050 metre contour. What followed was an outstanding alpine walk. Our route had us crossing alpine meadows and ducking in and out of fields of granodiorite boulders.

Several kilometres along we intersected the soggy headwaters of Merritts Creek. From here we swung north west, staying high but paralleling Merritts to where it crosses the Summit Track. This is a section of the Australian Alps Walking Track (AAWT) that joins Rawsons Pass (below Mt Kosciuszko) to Charlotte Pass.

On the Summit Track. Part of the Australian Alps Walking Track

We had stepped through into a parallel universe. From the solitude of Kangaroo Ridge we hit the teeming AAWT. Swarms of hikers and mountain bikers bustling along. All intent on summitting Mt Kosciuszko, at 2029 metres Australia’s highest mountain.

A short trot took us across Merritts and then the mighty Snowy River. We stood a mere two kilometres from its topmost seepages.

Seamans Hut

From the Snowy, the AAWT climbs up a steep pinch onto Etheridge Ridge and Seamans Hut.

Seamans is a nifty stone shelter on the Summit Trail below Rawsons Pass. The 7m X 3m granite stone hut was originally named the Laurie Seaman Memorial Chalet. A bit of a mouthful, so now is universally known as Seamans.

It was constructed in 1929 to commemorate W. Laurie Seaman who perished in a blizzard with his fellow skier, Evan Hayes. Seaman’s body was found leaning against a rock near the present site of the hut.

The two skiers had departed under blue skies but got caught in an afternoon blizzard while skiing off the summit of Kosciuszko. The men separated and Hayes’ body was found above Lake Cootapatamba. Lying on his skis. A cairn of stones marks the spot. He was found about one kilometre north of the hut on the side of Mt Kosciuszko.

An emergency shelter was built near Lake Cootapatamba c 1952 as an emergency hut for Snowy Mountains Authority Hydrologists on Cootapatamba Creek for a proposed diversion of its waters via aqueducts and tunnels to the Kosciuszko Reservoir on Spencers Creek. The Koscuiszko Reservoir proposal was abandoned in about 1965.

Seaman’s camera was retrieved and the processed photographs showed them standing next to Kosciuszko’s summit cairn.

Laurie’s parents travelled from the USA to visit the site where their son was found. They contributed 150 pounds to build a memorial shelter. The full story of the tragedy can be read in Nick Brodie’s ‘Kosciuszko’.

The hut now serves as an emergency shelter for skiers and bushwalkers caught out in Kosciuszko’s fickle alpine weather.

We ducked into Seamans for lunch and to dodge the westerlies that had been plaguing us all week. A quick bite, a gander at the hut’s log book and info board and we were off again. With the whiff of the finish line in the air, Chris, Neralie and Garry loped off, leaving Joe and I to wend our way back, at a pace more suitable for elderly gentlemen. A mere six kilometres downhill.

We fell in with happy throngs of summiteers. These ranged from two young turks who had just completed a 10 peaks challenge to a very stylish hiking couple. The latter, still to summit, were heading uphill at 2.30 pm, untrammeled by the weight of the basics like waterbottles, backpacks, rain gear and spare warm gear. Just Hokas, sunnies and light-weight outdoor apparel to speed them on their way to a sunset viewing from Kosciuszko summit. See photo below.

The Ten Peaks Challenge

I hadn’t heard about this 10 peaks lark, but I discovered later that it is a 64 plus kilometre peak bagging ‘challenge’ involving ascents of the highest Main Range peaks over a 24 hour period.

- Mt Kosciuszko 2228 m

- Mt Townsend 2209 m

- Mt Twynam 2195 m

- Rams Head 2190 m

- Etheridge Ridge Peak 2180 m

- Rams Head North 2177 m

- Alice Rawson 2160 m

- Abbot Peak 2159 m

- Abbot Peak East 2145 m

- Carruthers Peak 2145 m

All of which I had climbed with bushwalking companions over the decades, but certainly not in 24 hours. Commmercial operators offer two/three/four day packages if you are not confident about this alpine stuff. Our two young friends being made of sterner stuff, had completed the feat over a weekend.

Joe and I gladly soaked up the easier downhill pace and the enjoyment of extensive views down the Snowy River Valley far below us.

So ended another brilliant day out and about in Australia’s Snowy Mountains with my fellow Kosciuszkians Joe, Neralie, Garry and Chris. Mt Stilwell is a short walk but if you look around, there is much to interest even the casual hiker.