Up ahead, our path crossed its first cascade, then sidled up through stands of snow gum woodland, threading in and out of huge granite boulders before descending to a vast alpine grassland. With alpine scenery like this, and on a benign summer’s day, who could resist the opportunity to hike the new Snowy Alpine Walk?

by Glenn Burns

Certainly not me. Nor my walking friends Joe, Neralie, Chris and Garry. Surprising actually. Given the foul weather on our last foray together into the high plains of Northern Kosciuszko. Fortunately, my walking companions had remained undaunted by the cold wet weather over those six days. This time, however, a beneficent weather god smiled down on us. We luxuriated in sunny, pleasantly coolish, if somewhat windy days. Glorious alpine weather. Mr BOM promising a maximum of 17o C and a minimum of 8o C. But windy.

The Snowies Alpine Walk

In 2018 construction started on the Snowies Alpine Walk. The NSW Government boasted it would deliver ‘ a world-class, multi-day walk across the alpine roof of Australia in Kosciuszko National Park.’

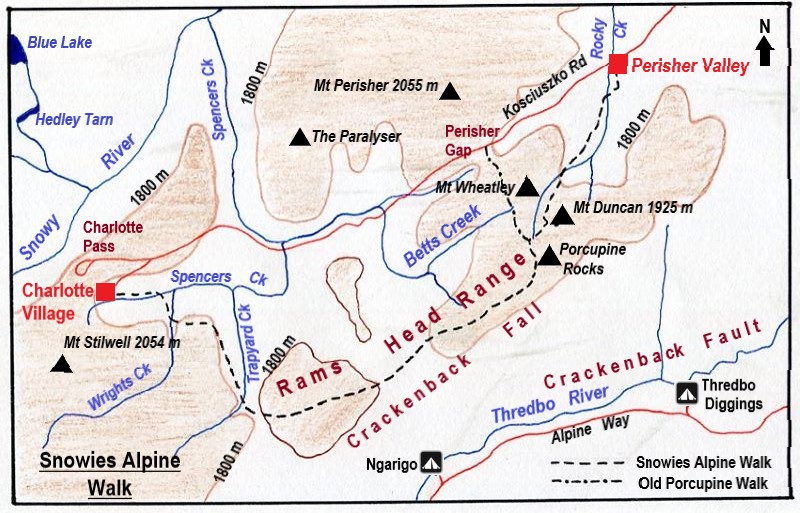

This is a 55 kilometre, 4 day walk connecting the existing Mt Kosciuszko-Main Range walks with three new sections. Namely, Charlotte Pass to Guthega Village; Charlotte Pass Village to Perisher Village via Porcupine Rocks and, as of 2024, the still incomplete section from Perisher Village to Bullocks Flat in the Thredbo River Valley.

Map: Perisher: 1:25000: Geoscience Australia.

Map of Snowies Alpine Walk: Charlotte Pass Village to Perisher Village via Porcupine Rocks.

Tuesday: Charlotte Pass Village to Perisher Village via the Porcupine Rocks: 13 kms.

An uneventful 25 minute drive took us from our Sawpit Creek digs to the start of of the day’s walk at Charlotte Pass Village. The corflute announcing ‘Cafe’ was duly noted by our resident caffeine addicts for future attention.

A Brief History of Charlotte Pass Village.

The first building at Charlotte Pass was the Charlotte Pass Chalet built in 1930 by the NSW Tourist Board ( NSWTB ). The NSWTB was prodded into action by the Seaman/Hayes tragedy in 1928 when both men perished in a blizzard on a skiing trip to Kosciuszko. It was thought that a much more efficient search could have been mounted from a site near Charlotte Pass.

The Chalet was burnt down in 1938 but was rebuilt for the 1939 season. For the next 30 years Charlotte Pass Chalet was the major centre of skiing in NSW. Since supplanted by the ski resorts of Perisher, Smiggins Holes, Guthega and Thredbo.

In 1962 the NSWTB leased the Chalet to a private company. A small alpine village sprung up, consisting of a hotel, private lodges, ski clubs, chairlifts, T-bars and Poma lifts.

Charlotte Pass was named after Charlotte Adams who, in 1881, was the first European woman to climb Mt Kosciuszko. Her father, Philip Francis Adams was Surveyor General of NSW from 1868 to 1887.

But we were on a different mission. A short stroll from the village took us to the track head.

Initially, the track heads over the boggy headwaters of Spencers Creek via a Cortan steel boardwalk. These boardwalks have spread like a rash over many sections of Kosciuszko’s alpine walks. But, dubious ambience aside, they do effectively minimise damage to fragile alpine ecosystems.

Bogs and Fens

Bogs are areas of wet, spongy ground usually found in areas of impeded drainage. Floristically bogs are dominated by spagnum moss (Spagnum cristatum) and associated with a variety of rushes and sedges, especially the tufted sedge (Carex gaudichaudiana) and the Australian cord rush (Restio australis). Bogs are formed by the decomposition of organic matter which will ultimately become peat.

From this point, at about 1770 metres, Spencers Creek wends its way downstream into the Snowy River some seven kilometres away. But for us, it was ever uphill to 1900 metres and the alpine grasslands and swamps that feed Spencers Creek and its major tributary, Betts Creek.

James Spencer

Spencers Creek was named after James Spencer, one of the first stockmen to take up a lease (Excelsior Run in 1880) and to graze his livestock on the ‘Tops’, including Mt Kosciuszko. The run extended over an area of 12,000 hectares.

The story goes that he fell off his horse attempting to drive his stock across a swollen alpine creek. That creek now bears his name, Spencers Creek. Spencer also named the nearby peaks of The Paralyser (1942 m) and Mt Perisher (2054 m).

His homestead was built lower down at the junction of the Snowy and Thredbo Rivers. That location, West Point, now Waste Point, was a favoured camping area for aborigines travelling to the high country to feast on Bogong moths. But more on mothing later.

Spencer’s other sideline was to act as a guide for visitors wishing to climb Mt Kosciuszko and explore other parts of the Main Range. Notables whom he led into the high alpine peaks included Thomas Townsend (surveyor), Baron von Mueller, Surveyor-General Adams and Dr von Lenderfeld.

Once on the southern bank of Spencers Creek the track rambles ever upwards through snowgum woodland to the 1800 metre mark, before thankfully, levelling off and contouring to the south-east. Wrights Creek, a tributary of Spencers Creek, is crossed as the track curves around a major SW-NE trending spur of the Rams Head Range.

Soon after the start of the climb onto the Rams Heads we met a bunch of older walkers perched trackside taking a quick breather. The first of many groups of hikers. The newly minted SAW tracks are obviously a big hit with summer visitors, and must be making the New South Wales Parks people very happy with their investment.

By now Garry had disappeared from my radar. But, having walked with him before, I knew there was no need to be concerned. He is a super fit, experienced walker. Soon enough we would find him waiting patiently at the next track junction or even, on occasion, having a catnap in a patch of springy snowgrass. And I could rely on him to suss out the best spots for our morning tea and lunch breaks.

This time we found him idling in a pleasant glade with its own steel bridge spanning a gently cascading stream. Just the spot for morning tea. This was Trapyard Creek, a tributary of Spencers Creek. Upstream were falls and cascades, while downstream was Johnnies Plain on the southern bank of Spencers. The plain below is strewn with striated boulders providing evidence of the Pleistocene glaciation in the Kosciuszko area.

Johnnies Plain and the Kosciuszko Reservoir

At the start of the Snowy Mountains Scheme in the early 1950s, Johnnies Plain came within a whisker of being flooded. The background to this was that the wily SMA Commissioner, William Hudson, had to get a couple of projects on the go quickly to placate his political masters , some of whom were pretty twitchy about the whole scheme.

One of the projects on Hudson’s early bird list was a high altitude reservoir on Spencers Creek, to be completed about 1954. The Kosciuszko Reservoir.

At 1780 metres above sea level, the reservoir would have inundated Johnnies Plain and lapped up to the back door of the Chalet in Charlotte Village.

It was to be fed by Betts and Spencers Creeks and 150 kilometres of water races and aquaducts including one contouring along the western face of Mt Kosciuszko. Like the proponents of the the Lake Pedder debacle in Tasmania, these people had little sense of environmental stewardship. But, to be fair, in later phases of the scheme, the SMA’s work on soil conservation and landscape restoration was world-class.

Fortunately, test drilling revealed that the footings for the dam wall would be in moraine rubble and not solid rock. The engineers proposed a number of hare-brained work-arounds including some process to freeze the unconsolidated moraine.

Also the SMA feared a PR thrashing if it attempted to flood a pristine alpine environment. The project finally stalled when the Kosciuszko State Park Trust declared the Kosciuszko Primitive Area to be closed to road and engineering works, buildings and commercial activities. Vale the Kosciuszko Reservoir.

Of course, within a few short years equally damaging commercial ski developments took place around the periphery of the Kosciuszko Primitive Area. By and large, all blights on the landscape, if you want my opinion.

Back on the track, our supplies of chocolate bullets, nuts and crystallised ginger dispatched, we puffed our way up onto the 1900 metre summit spine of the Rams Heads. Here were jagged outcrops of granodiorite, their outlines cutting a perfectly blue and cloudless skyline. Hence, I imagine, the derivation of the name Rams Head Range.

Then followed a gentle 150 metre descent into a vast grassy alpine saddle separating the north flowing Betts Creek headwaters from the Thredbo River system off to our south. The ‘grassland’ was a typical Tall Alpine Herbfield found over much of Kosciuszko’s terrain above 1800 metres.

Tall Alpine Herbfield and Tussock Grassland

The Tall Alpine Herbfields are the most extensive of all Kosciuszko’s alpine plant communities and are found on well-drained and deeper soils. These herbfields occur on a variety of bedrock types , suggesting that lithology has a negligible influence on location.

This plant community is the most diverse of all the alpine vegetation types in terms of number of species. Showy wildflowers grow in a matrix of snowgrasses (Poa caespitosa) and sedges (Carex sp). Technically, it is an association dominated by the genera Celmisia and Poa.

Wildflowers which I recognised included: silver snow daisy (Celmisia astelifolia), Australian bluebells (Wahlenbergia spp), star buttercups (Ranunculus spp), bidgee widgee (Acaena anserinifolia), Australian gentians (Gentiana spp), eyebrights (Euphrasia spp), billy buttons (Craspedia uniflora), and violets (Viola betonicifolia).

These summer wildflower displays are invariably spectacular, matched only, in the Australian context, by the wildflowers of the south-west of Western Australia.

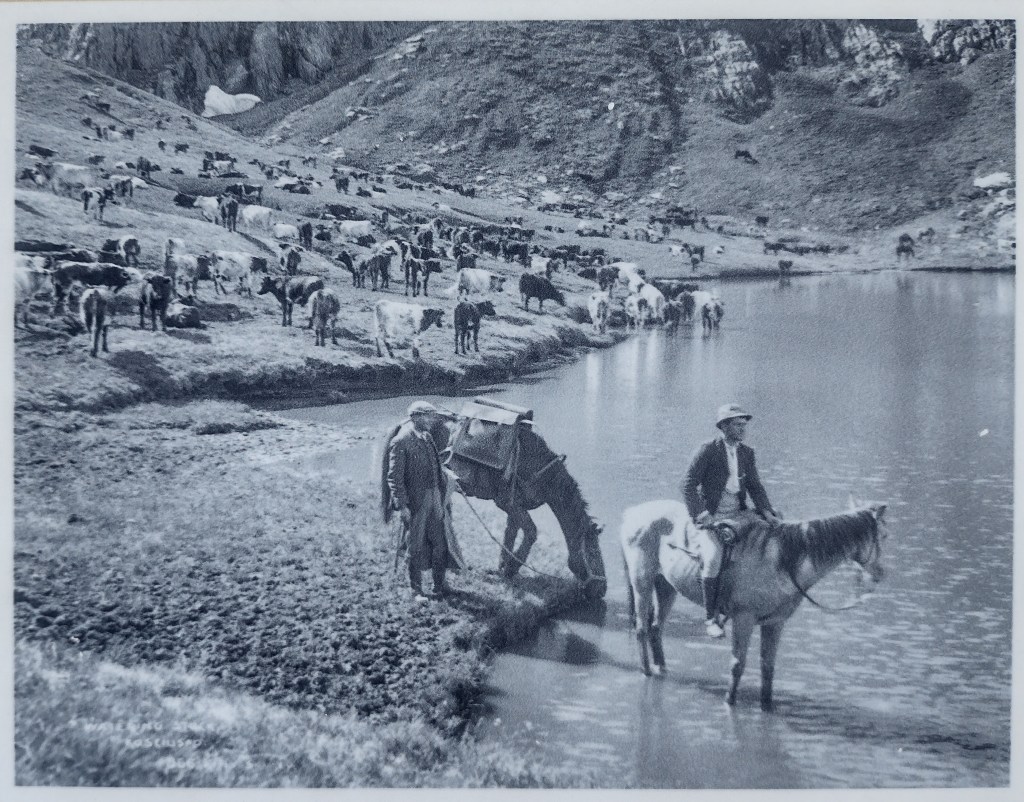

During the era of extensive sheep and cattle grazing across Australia’s high country, some of the more palatable plant species were pushed to the edge of extinction as sheep and cattle munched away at their preferred herbage.

Fortunately, small pockets survived in ‘refuges’ in rocky outcrops. Thankfully, sheep and cattle were given their marching orders with the declaration of Kosciuszko National Park in 1969. In the decades since, the threatened species have been re-colonising their earlier habitats.

The Crackenback Fault

From our vantage point in the saddle we peered over into the 600 metre Crackenback Fall to the Thredbo River Valley far below.

This spectacular fall can be explained by a combination of tectonic uplift (called the Kosciuszko Uplift) during the Tertiary (66 to 2.6 mya) and the rapid downcutting of the Thredbo River into the shattered bedrock along the Crackenback Fault. The Crackenback Fault dates back to the Tabberabberan tectonic contraction of the Lachlan orogeny some 390 to 380 mya.

Thus, the Thredbo flows in a reasonably straight line from Dead Horse Gap to Lake Jindabyne. A consequence of the structural control exerted by the Crackenback Fault.

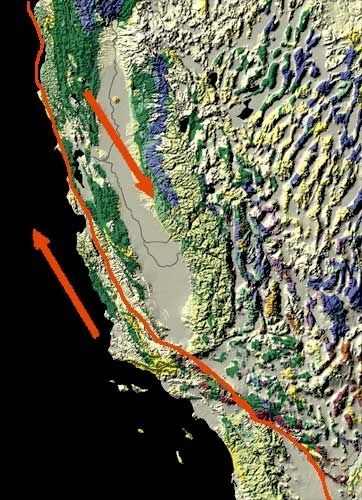

The course of the Thredbo River presents an interesting drainage pattern when viewed on a map. It is described by geomorphologists as a rectilinear drainage pattern, where the main bends of the Thredbo River change direction at right angles. In the case of the Thredbo, it initially flows south-east, then turns south-west, then north-west and finally into the main Thredbo valley which runs north-east to Lake Jindabyne.

Map showing rectilinear drainage pattern of Thredbo River and the influence of Crackenback Fault

Joint lines are structures along which there has been no discernable differential movement. Large scale joints are are common feature of granitoid landscapes, like the Rams Heads.

Faults, however, show clear evidence of differential earth movements. The Crackenback Fault is a 35 kilometre long, south-west to north-east trending strike-slip fault between the Jindabyne Thrust Fault (at Jindabyne) and Dead Horse Gap.

A strike-slip fault has horizontal movement of the earth’s surface with little vertical displacement. It is along this straight fault structure that the Thredbo River flows towards Lake Jindabyne.

Other well-known strike-slip faults include New Zealand’s Alpine Fault, the Dead Sea, and the San Andreas fault in North America.

San Andreas Fault. North America.

Meanwhile, high above the Thredbo River, the saddle gave way to another climb, another group of elderly hikers and further on, Garry, bunked down in a grove of snow gums.

By now my fellow walkers had lost interest in Crackenback faults, Crackenback falls and such like geological POIs and were insinuating that lunchtime was long overdue. Our lunch spot should preferably be sheltered from the wind. North-westerlies were idling along at about 30 kph. Somewhere sunny, with a view would be nice. My advance scouts came up trumps. A spectacular eyrie on a jumble of boulders looking down the steep Crackenback Fall to the Thredbo River far below.

This was an ideal lunch nook. Grand views, a pool of warm sunlight, and a chance to keep tabs on the passing elderly bushwalker caravanserai plodding its weary way along the path below. Wafting up to my rocky perch were bleats of dismay as the final steep climb to Porcupine Rocks hove into their view. My turn would come.

Porcupine Rocks

Half an hour later I too was obliged to struggle up said ridge and clambered onto the bouldery outcrops known as Porcupine Rocks. Their appearance explains the name. Piles of shattered, pointy boulders on the crest of the Rams Head Range extend for 25 kilometres in a SW to NE axis. The highest point is Mt Duncan trig at 1926 metres.

These are outcrops of Silurian Mowambah granodiorite (443 to 419 mya). Granodiorite is a coarse-grained intrusive rock similar to granite.

The spine of tooth-like boulders is a consequence of the tendency of granitic tors to weather in sheets. Then severe freeze-thaw action further breaks down the edges of boulders to give the characteristic jagged appearance of granitoids in cold alpine climates.

You can climb any of the boulders easily for fine views 800 metres down into the Thredbo Valley extending from Dead Horse Gap to Lake Jindabyne.

I have been here a number of times before and mused that we were standing at a crossroads in time. Present, early National Park days, grazing era and the distant past.

Pathways through Time

Kosciuszko’s most recent path is the freshly minted Snowies Alpine Walk. Built to entice visitors to the Snowy Mountains during the summer downtime. Walkers can now easily access previously lesser known parts of the Main Range.

New, also, in techniques of path construction. This was no rough bushwalker’s pad through the scrub. It is a wide, heavily engineered path.

Surfaces have been hardened by the placement of massive stepping stones of granite retrieved from the old Snowy adit rock pile. The interstices filled with compacted granite. Fragile bog and fen areas and creeks are bridged by boardwalks of Cortan steel.

Given the hordes using the track today, I can well understand Parks thinking on the use of hardened track surfaces.

If visitor useage is a measure of success, the push for summer tourism has succeeded. The place was awash with active oldsters and legions of pint-sized trampers out in the fresh air on school excursions to the Snowy Mountains.

This onlooker was impressed by their youthful energy and boisterous enthusiasm. They were still going hammer and tongs after having already trekked the 12 kilometres from Charlotte Pass. Their principal less so. A recumbent figure sprawled trackside.

The old bushwalking pad and ski trail to Porcupine Rocks

Pre-dating the SAW are my earlier strolls to the Porcupines. These began at Perisher Gap. From the Perisher Gap car park a rough bushwalker’s pad and ski pole line contoured around Mt Wheatley (1900 metres).

I often gave Mt Wheatley a miss as it is a pile of boulders overgrown with snowgums and an understorey of whippy, prickly shrubs. But if you persist and don’t mind a scratch or three, it does give an excellent view of much of the highest parts of the Kosciuszko Plateau. Between Wheatley and Porcupine Rocks the terrain is much more open as you leave the snowgum woodland and cut onto the high alpine meadows and bogs of upper Betts Creek. Wet boots always guaranteed. It was rare to see any other walkers.

Old Kosciuszko Road

Older still, in the grazing era, was the Old Kosciuszko Road which passed by the Porcupine Rocks on its way to summer pastures and Mt Kosciuszko.

The Old Kosciuszko Road (circa 1870 to 1898) started on river flats near Old Jindabyne and passed near The Creel before ascending a spur east of Sawpit Creek. From there it went through Wilson’s Valley, Boggy Plain, Pretty Point and ascended to pass by the Porcupine Rocks. Then it edged south-west, paralleling the spine of the Rams Head Range to Rawsons Pass.

It was used mainly by graziers bringing stock up to high summer pastures.

A later Kosciuszko Road (1908) avoided the Rams Heads and followed valleys through through Smiggins Holes, Perisher and The Chalet before ascending to Rawsons Pass. Essentially the same route taken today.

Aboriginal Pathways

Aborigines ranged over Kosciuszko’s high alpine country during the summer months. Their stone tools have been found nearby at Perisher Gap as well as Mt Guthrie, Mt Carruthers, Little Twynam and the Rams Head Range.

It is likely that they followed ancient pathways to the high tops of the Ram Heads and the Main Range in search of a major food source, the Bogong moth (Agrotis infusa).

The Bogong moths migrate from the hot inland plains of New South Wales and southern Queensland to hibernate in the cool rocky crevices and caves of Kosciuszko’s granitoid landscapes.

The aborigines, too, migrated to the high tops to feast on the moths. They came from far and wide. From Yass and Braidwood, from Eden on the coast, and from Omeo and Mitta Mitta in Victoria.

Europeans often commented on how sleek and well fed the aborigines looked after their moth diet. Edward Eyre who explored the Monaro in the 1830’s wrote: “The Blacks never looked so fat or shiny as they do during the Bougan season, and even their dogs get into condition then.”

At summer’s end, with the arrival of the cold southerlies, the moths and aborigines decamped and headed for lower altitudes. As did my walking companions.

Tempting as it was for me join our still recumbent principal for a quick kip, my companions had already galloped off. A final descent of 3.5 kilometres to Perisher village followed, where Garry had stashed his ute. The new SAW track follows the old bushwalking pad downstream along Rocky Creek to Perisher Village.

The walk exit at Perisher was still a work in progress. Rangers had set up a diversion around the final section of track. Here Joe and I caught up with Neralie and Chris chatting with two young track builders. Extracting useful information as is their wont. Apparently the rangers were experimenting with another system of hardening track surfaces in preparation for the final Perisher to Bullocks Flat section.

And so, after six hours and 14 kilometres, a most satisfying day of alpine walking was over. Garry’s ute waited patiently at The Man from Snowy River pub to ferry its passengers back to Charlotte Village where we retrieved the Joemobile.

Who could ask for a better bunch of walking companions? Thanks to Neralie, Garry, Chris and Joe for sharing the day with me. And I still had many more days of alpine adventures up my fleecy sleeves for their delectation.

Accommodation

I chose to hike sections of the SAW as day walks. We overnighted in a heritage-listed chalet at Kosciuszko Tourist Park, Sawpit Creek. Our abode was a little shabby on the outside but clean and refurbished inside. Entirely satisfactory for our purposes.