With one son about to depart overseas for several years, a nostalgia outing to Tassie seemed in order. However, the planned ascent of Frenchmans Cap was thwarted by an unexpected health issue in the old codger. Undeterred, we settled for the benign and familiar pastures of Cradle Mountain and Cape Raoul.

Our grown-up children have dispersed across the continent and overseas. We have bushwalked, camped and canoed with these sons since they were babies; first carrying them in baby backpacks before eventually gifting them their own packs and gear. Holidays meant bushwalking, camping and canoeing. This is what our family did and they accepted it…. mostly.

As a young family and adults we were fortunate to roam far and wide over Tasmania’s wild landscapes, enjoying some of Australia’s best bushwalking. So what better place for a farewell walk and catch-up.

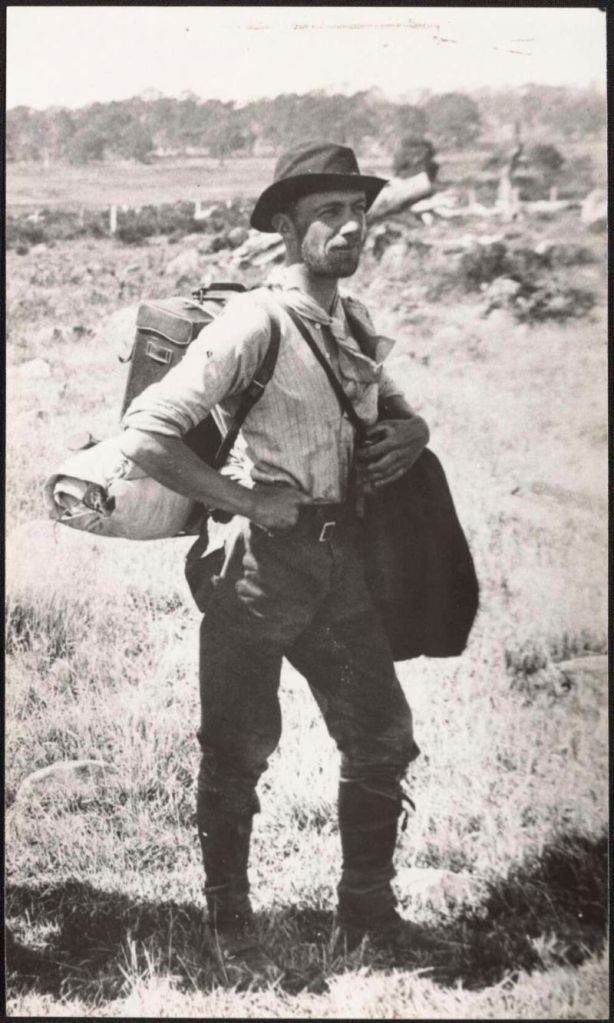

Out for an evening stroll. Overland Track 1990s.

Saturday

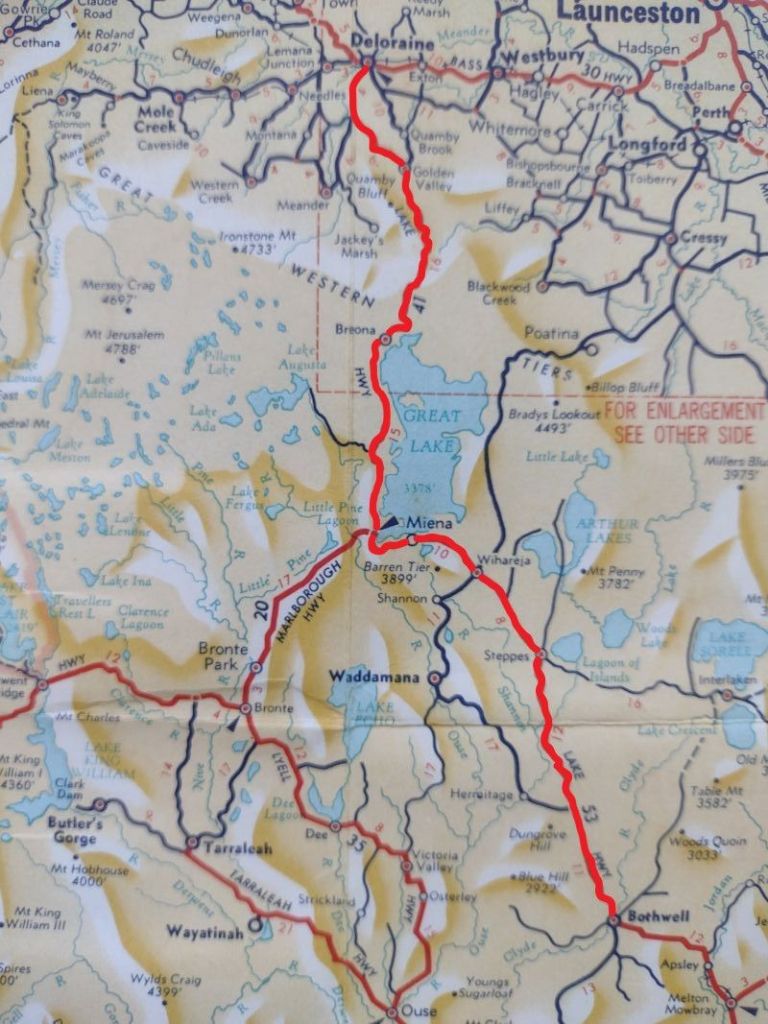

And so, on a soft gray Tassie Saturday afternoon in March, three lads and I met at Hobart Domestic Terminal and piled into our hire car. Wife had opted out of this boys-own expedition. Mid afternoon we swung onto the A1 and headed north for Deloraine, overnight. Thence to Cradle Mountain for a few days of hiking.

With the youngster at the helm, we headed off on his preferred ‘scenic’ route over the Central Plateau, the Great Western Tiers, thence to Deloraine. And it was all very scenic. But also windy, cold and misty.

Central Plateau and Highland Lakes Road

An hour later we exited the A1 at Bothwell and headed NW along a very tortuous A5, aka the Highlands Lakes Road, climbing up to the alpine Central Plateau at 1000 metres. Today, under a leaden sky these windswept plains were pretty dismal. But, as I tried to impress on the offspring, very interesting geologically. Though I sensed some resistance to matters geological. At best, mild enthusiasm, of the ‘let’s humour the old dad’ kind for these recently glaciated 183 million year old Tasmanian dolerite and basalt outcrops.

But the good news was that I would get another chance to harangue them with more geologic gems when we returned to the Central Plateau to check out Little Pine Lake on the morrow.

The Central Plateau is a landscape dominated by glacial lakes. The A5 skirts the Great Lake on its western side. The lake is vast. Thirty kilometres on its long north-south axis and eleven kilometres east-west. I read somewhere there are 4000 lakes on this plateau and looking at my topo map I wouldn’t be surprised by this claim.

Strung along the shoreline are a series of little villages: Miena, Liawenee, Reynolds Neck, Brandum, Breona and Doctors Point. All of a type: mainly ‘huntin’ n ‘fishin’ style cabins and lodges. Preppers according to son two.

The nearby Murderers Hill, Stony Plain and Wild Dog Plains suggestive of the frontier landscape that it once was. Throw in a long freezing Tassie winter and it would have been, indeed, a tough life. And probably still is.

Our arrival at the Deloraine Motel was heralded by the first spits of the predicted three days of rain/sleet/snow. As we extracted ourselves from the hire car I spotted two bikies lurking on the verandah. No doubt checking out the mainland blow-ins piling out of their townie hire car. Deloraine (pop 3000) is a typical Tassie rural service centre: a bit daggy but having all the accoutrements for locals and any passing tourist trade heading for Cradle Mountain: a few pubs, a bakery, cafes, motels, Woolies supermarket, riverside walk and a service station.

First order of business, a decent feed and a few Boags at ye olde worlde Empire Hotel. Not bad tucker actually. I wolfed down a generous serving of Westbury gourmet sausages served with creamy mashed potatoes, grilled broccolini in a red wine jus. Just a fancy pants bangers and mash with a price to match. The lads tucked into their predictable pub grub: pizzas, parmies, burgers and Boags.

Before retiring for the night there was the small matter of provisions for the next few days. On reaching the supermarket, the food list which I had sweated over for hours and emailed out, was promptly discarded. As had been, I should mention, my detailed gear list. The lads scattered to the four corners of the store carting back armfuls of their favourite travel/hiking foods. It was pretty obvious that my suggested Back Country freeze dry Spag Bol and wheatmeal biscuits wouldn’t cut it.

Sunday

Rain drummed down most of the night and daylight brought a damp, overcast and cool morning. Not the best weather for hiking at Cradle. The official BOM forecast was not encouraging so dossing down in a Waldheim bunkhouse at Cradle now appeared a more palatable option than three days of tenting trackside in rain and sleet on Frenchmans.

Today, Sunday, was a benign 9oC to 14oC with 25 mm of showers. Reasonable. Monday was all downhill: 2oC to 7oC with more showers and sleet and snow at altitude. Things picked up for our final day at Cradle: 4oC to 11oC with occasional showers.

A quick feed of weetbix, sliced banana, my cheapskate muesli, a coffee and we hit the road. But not to Cradle. First, we backtracked to the Central Plateau to have a gander at Little Pine Lake. One of the 4000 glacial lakes found there.

Little Pine Lake

This gem of a lake is set high up on the Central Plateau at 1200 metres. Tasmania Parks have provided a boardwalk from the car park to lake’s edge. A matter of walking only 500 metres. Close enough to tempt the passing tourist trade.

It is a little slice of Central Plateau alpine landscape: moorland, bogs, glacial lakes, dolerite ridges, massive talus slopes and clumps of those ice age survivors, pencil pines. The landscape is largely the product of the last phase of Pleistocene glaciation some 20,000 to 10,000 years ago.

The Pencil Pine: a Tasmanian Paleo-endemic

Paleo means ancient and endemic means found only locally. That is, the Pencil Pine is an ancient tree found only in Tasmania.

The very slow growing Pencil Pine (Athrotaxis cupressoides) prefers wet soils, hence is characteristically found on flat ground at the edge of tarns, lakes and watercourses. It is the most frost resistant of Tasmanian trees and can tolerate temperatures that kill other trees. Hence it survives up here in the high alpine zone.

Athrotaxis usually grows as an isolated plant or in small clumps. It reproduces from cones which only release seed every ten years or so. Apart from this slow reproductive rate, it is also highly susceptible to fire and will be under threat if the climate continues to warm.

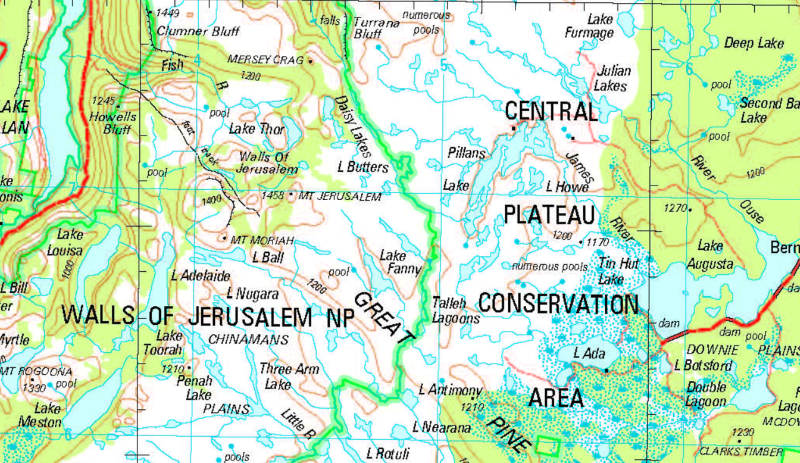

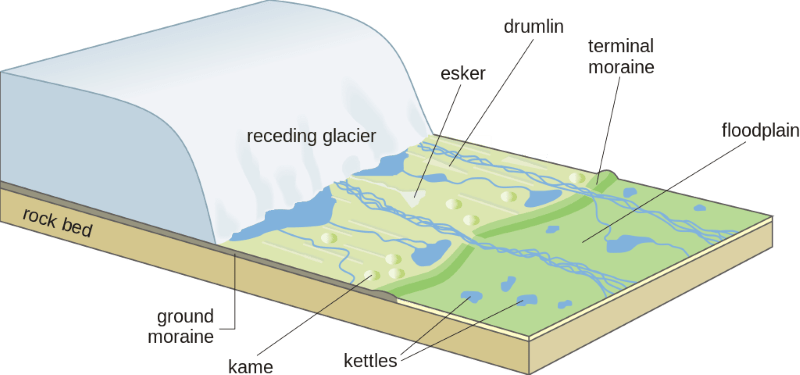

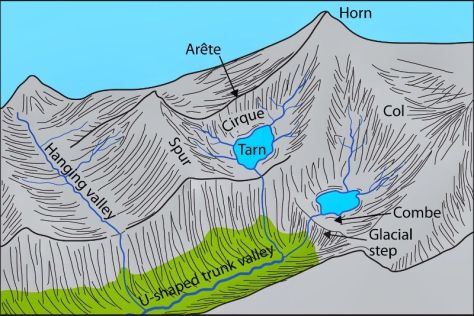

The Pleistocene Ice Age comes to the Central Plateau

It is thought that an ice cap 65 kilometre across covered much of the Central Plateau. Its legacy preserved in The Walls of Jerusalem National Park and the Central Plateau Conservation Area. The latter somewhat of a misnomer given the loggers are still busy plundering the forests here. The ice cap covered most of the plateau, even peaks standing over 1500 metres today (like Mt Jerusalem at 1459 metres). But towards the limits of the ice cap the ice thinned and flowed around the highest peaks leaving them as rocky outcrops known as nunataks. A landform still found in the Antarctic today.

The erosive power of moving glacial ice cut depressions into the bedrock which later filled with water, forming some of the myriad of glacial lakes we see today.

As well, the retreating ice front (snout) dumped piles of moraine which banked up fluvioglacial streams to create even more lakes. Little Pine Lake is fed by Little Pine River, a tributary of the Nive River. It rises nearby in the Great Western Tiers.

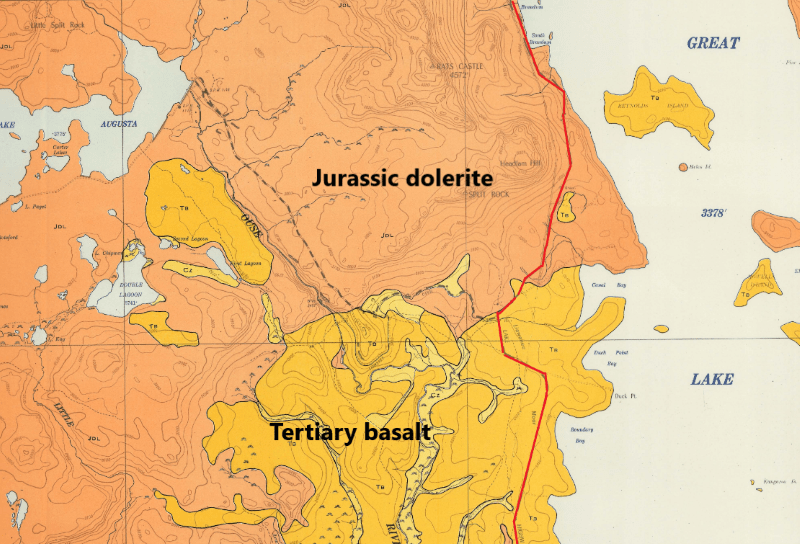

Having exhausted the Pleistocene geology of the Central Plateau, it was time to tootle off to Cradle Mountain. But not before a further excursion into Tasmania’s ancient geological history. All visible from the comfort of our warm hire car. The bedrock of the Central Plateau is predominately capped by basalt (younger) and dolerite (older). These basalt and dolerite surfaces have been scoured by the geologically more recent Pleistocene ice caps and valley glaciers, creating much of the scenery we see today.

Gondwana tears asunder

About 65 million years ago as Australia and Antarctica finally pulled apart, massive quantities of basaltic magma poured from fissures in the earth’s crust and covered swathes of the landscape of the Central Plateau. This period, known as the Tertiary, saw widespread volcanism across eastern Australia, and indeed, on a global scale. Extensive flows occurred on the Central Plateau with lava also filling ancestral valleys of the Derwent and Tamar Rivers whose headwaters are to be found on the Central Plateau.

The Older Dolerites

Capping the Central Plateau and the Great Western Tiers are spectacular columns of 185 million year old Jurassic Tasmanian Dolerite, displaying the typical ‘organ pipes’ effect. These polygonal columns formed by the cooling of magma contracting under and in (sills and dykes) the overlying beds of sedimentary rocks. This occurred at the breakup of the super continent Gondwana, when Australia and Antarctica were finally separating.

As the sedimentaries eroded away, vast swathes of Tasmania revealed a capping of hard dolerite. Dolerite outcrops are invariably fringed by massive talus slopes of frost shattered dolerite. Tasmanian Dolerite covers about 40 percent of Tasmania, said to be the largest province of dolerite on the earth and is a rarity globally.

Ancient Marine Sediments

Leaving the plateau, the A5 zig-zags down the 500 metre escarpment of the Great Western Tiers to more geological delights. Here, outcropping in road cuttings are the oldest rocks. Ancient quartzites and schists date back some 1100 million years ago, before life had begun on land (Proterozoic). ‘Tasmania’ was at the edge of Gondwana.

Thick layers of sand and mud washed off this land mass and were deposited in a vast area from what is now Rocky Cape in the north through Cradle Mountain, the Central Plateau, and Frenchmans Cap to the south coast.

The sediments compacted to sandstone and mudstone, with later earth movements metamorphosing the sandstone to become quartzite and the mudstone to schists and phyllites. The quartzite, being very hard, forms some of Tassie’s most spectacular mountains.

Cradle Mountain World Heritage Visitors Centre

We pulled into the vast car park of the Cradle Mountain Visitors Centre. Pretty much chockers even on this cold, windy and drizzly day. Not having been to Tassie for a number of years, I was taken aback by the sheer numbers of tourists, appropriately clad in outdoorsy clobber: hiking pants, puffer jackets, beanies and rain jackets.

Inside the warm Visitors Centre number three son sorted out our passes and cabin keys. The rest of us had a waddle around. Disappointing, comes to mind. For a World Heritage Area building, presenting the Cradle Mountain Wilderness Area and Overland Track to the world, it could be anywhere on the international tourist trail.

A busy Covid central café; check–in lanes for park and shuttle bus passes; a high-end tourist gee-jaw trap with $200.00 soft toy wombats or $16.00 fridge magnets. No sign of a cost-of-living crisis here. Overall, depressingly commercial but enticingly warm. A well appointed airport terminal comes to mind.

Made of sterner stuff than I, the lads forsook my suggestion that we check out the heated cosy café and its epicurean delights and, instead, ducked off to the outside ‘shelter’ shed (in name only), for a bite to eat. Cheds, chunks of bread, slabs of cheese served up with the cold reality of foul weather for a few days.

Then onward to the freezer-box aka the Interpretative Centre. It had seen better days. I swear the exhibits were much the same as I had seen some years ago. Still sporting photos, tat and piles of display folders. But the folders had heaps of useful natural history stuff. I was taken in by a pair of ancient tennis racket snowshoes tacked to a display wall. Canadian Mountie style. The troops, by now needing to thaw out, stalked off to the start of the Enchanted Forest Walk.

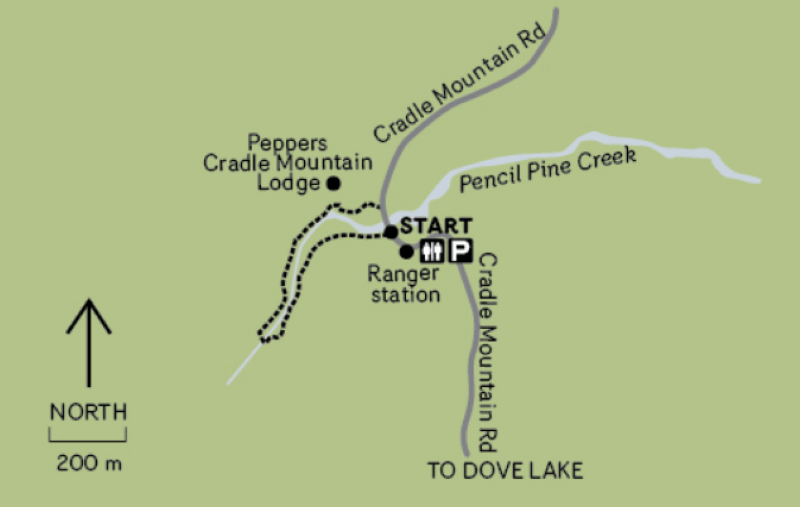

The Enchanted Forest Walk

This easy 1.1 kilometre circuit gives visitors a quick taste of Tassie’s subalpine wilderness. It starts and ends at the Pencil Pine Creek bridge and the hardened path makes it suitable for all comers. As the track heads upstream on Pencil Pine Creek it passes through button grass moorland.

Button grass (Gymnoschoenus sphaerocephalus) is a sedge that grows in large clumps or tussocks and dominates the flatter boggier terrain around Cradle Mountain. It is unmistakable with hard, dark button-like seed heads and long slender green-gold leaves.

Leaving the button grass moorland, the track then ducks into cool temperate forest which lines the banks of the creek. The three trees which I could identify were myrtle beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii), deciduous beech (Nothofagus gunnii) which is the only winter deciduous tree in southern Australia, and pencil pine (Athrotaxis cupressoides).

The circuit exits the forest at Peppers Cradle Mountain Lodge which fortuitously houses a public restaurant and boozery. A cursory glance inside revealed the clientele enjoying a tankard or three and tricked out for their next adventure when the misty rain cleared. Again, surprisingly, the offspring passed on a schooner of Boags with Gen Boomer and hot-footed it off to our digs in a cabin at Waldheim. Apparently, we were here to do a lot of hiking.

Waldheim Cabins

Not in the same class as Peppers , our rustic bunkhouse sported two bedrooms with two double bunk beds each, a small but functional kitchen/dining area with all mod-cons. Heaters kept the rooms at a toasty 13oC. Very cosy. The freezing midnight trip to the outside ablutions block a less attractive proposition. But a big bonus of the Walheim Cabins is their proximity to the start of the Cradle Valley/Mountain walking tracks and our isolation from the hordes at the ritzy Peppers or Cradle Big 4.

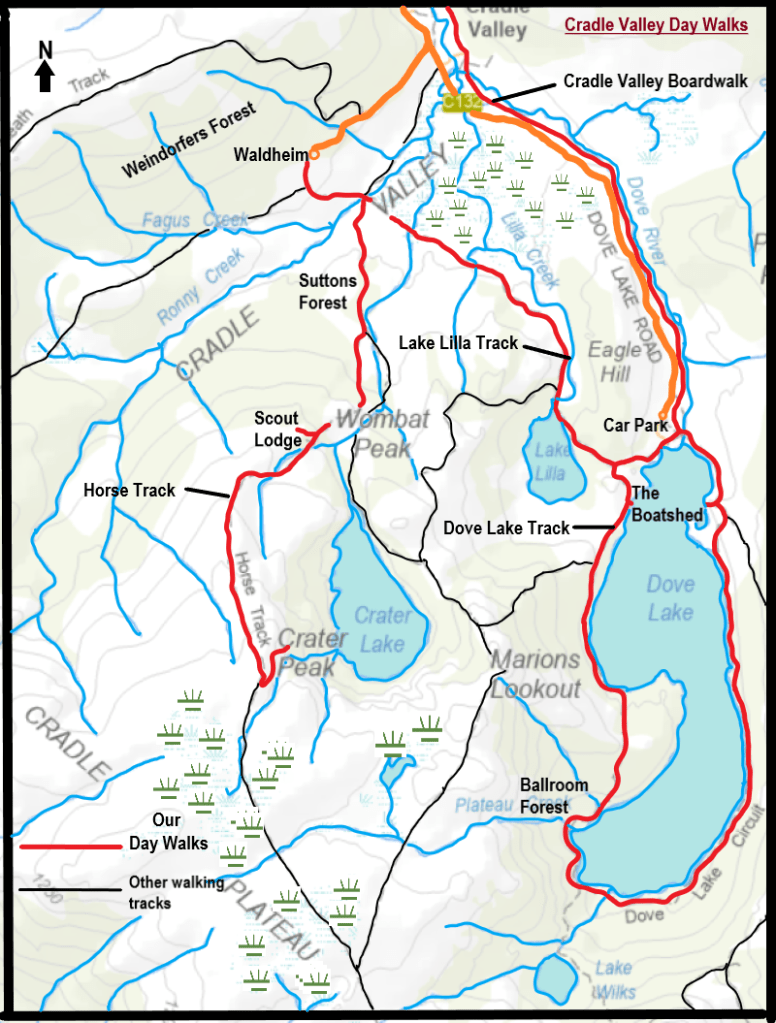

Map of our walks in Cradle Valley

I quickly got a message that slacking around in the comparative warmth of cosy Karana was not on this afternoon’s agenda. Donning our WW2 Atlantic Convoy Kit we ventured out into the elements. As befitting born and bred Queenslanders, we had made the incongruous decision to step out in shorts rather than long trousers and rain pants. They breed them tough and stupid north of the border.

Middle child, having more experience of living through miserable cold wet winters, was suitably togged in long trousers and Hi-viz fleece. The latter, he announced, so we could find him in the snow tomorrow.

After several hours of slogging along in the wind and freezing rain I swear my bare legs were borderline frostbitten and discoloured with great red blotches. My ancient foxed and furred Tyrone T. Thomas Tassie tome advised that:‘Warm, waterproof clothing is essential’. His italics for emphasis. Lesson learned.

The afternoon’s plan was to nip over to Dove Lake and the Boat Shed. Which was a good choice given that the surrounding tops were shrouded in mist and rain. As, indeed, was our lowland option. Wind, rain, and mist. This is an easy six kilometre return walk via Lake Lilla, all on boardwalks and tracks.

The Boatshed

The boatshed was built by the area’s first Ranger, Lionel Connell in the 1940s. The shed was constructed mostly of King Billy Pine. Some restoration work was done in 1983 but the shed is mostly original. The now vacant structure was commonly used until the 1960s. Huon Pine boats ferried passengers around the lake in the 1930s. The boatshed provides the reference point for photos of the stunning mountain scenery.

We made it back to Waldheim, drowned ship rats; changed into warm gear, hovered over the wall heaters and rigged up our wet kit to dry overnight. My chefs got busy with a pasta extravaganza, having rejected my offer of sachets of freeze-dry Back Country Beef Teriyaki or Spag Bol.

Monday

And so to the day of our main walk in Cradle Mountain. I peeked out. The high tops were dusted in snow with cloud building quickly. Showers and mist drifted over the moors below our cabin. The BOM promised a 2oC minimum and 70C maximum for Cradle Valley. And that’s a forecast somewhere 600 metres lower than the high tops.

The Horse Track

Our planned walk was to nip out of our front door, cross Ronny Creek, turn right, take the Horse Track to Crater Peak, tootle along the exposed Cradle Plateau, swing down to Marions Lookout and head back to Waldheim. An easy day walk.

I had walked this track to Kitchen Hut and back via the Face Track way back in the late summer of 2007, so I convinced the troops that a jaunt on the Cradle Plateau was right up our alley.

All well and good in fine weather, but this time, just above the Scout Lodge at 1000 metres, things turned decidedly nasty.

Tyrone T. Thomas describes the walk from Waldheim onto the Cradle Plateau as ‘unforgettable’. Which it was. Just not in the way he meant. The distant views of snow on the tops and the wind gusts in nearby trees gave us a clue as to what would unfold on the high tops.

Both cues for us to now don full Arctic Convoy kit. This time remembering we were in alpine Tasmania not sub-tropical Queensland. We gave up a lifetime of walking in shorts and gaiters and togged up into long trousers, rain pants, gloves, fleece coats and thermal shirts.

From our front door we ducked out onto open snow grass moors and descended to Ronny Creek courtesy of a netted boardwalk. The snow grass is predominately Poa gunnii, which, like button grass has a tussock habit. But it is a true grass with long blue-green leaves and feathery spikes for flower heads.

The weird looking plants found near this boardwalk are a grove of Pandani (Richea pandanifolia). Each plant has a single thin stem rising to a crown of green strap-like leaves and a skirt of grey dead leaves which hang untidily from the stem.

And if you are keen to see wombats, this is the place to be. The tourists thought so too. Endless streams of puffy jacketed visitors wander up the Ronny Creek boardwalk in the hope of spotting a wombat. And they aren’t disappointed. This is a veritable wombat Serengeti, with herds of them grazing even in the middle of the day. Seemingly unfazed by the predations of dozens of camera wielding humans.

But for us, we headed for the Horse Track which traverses the high tops. Initially, the track crosses Ronny Creek and climbs gently through a landscape of hummocky button grass. Not far along, the Overland Track hives off to the left. But we turned right onto the Horse Track. From here a steep and very rough path weaves ever upward along the edge of Suttons Forest towards the Scout Lodge turnoff. Several hundreds of metres of altitude gain.

Suttons Forest is sub-alpine woodland dominated by Tasmanian snow gums (Eucalyptus coccifera) and Alpine yellow gums (E. subcrenulata). But I was too pooped to engage in surveying the understorey plants. Persistent scuds of rain/sleet quickly dampened my enthusiasm for things botanical.

Or much else, apart from keeping on the move to stave off the cold seeping into my gloved fingers. Suffice to say the understorey looked very wet, prickly and dense. Suttons Forest was named in the early 1900s by G. Weindorfer after Dr C.S. Sutton of Melbourne who did extensive botanical surveys of Cradle Valley.

Soon after the Scout Lodge we popped out onto the alpine zone at 1000 metres. In the main, Australia’s alpine landscapes and weather are pretty benign in the global context.

But, today, even here the weather was moderately unpleasant. Gusting wind and snow is potentially dangerous wherever you are on the planet. We had the right gear but a biting wind was scouring the Cradle Plateau. Middle son , realising what was about to unfold, retreated to more equitable pastures.

The track, partly board-walked, climbs steadily on a NE-SW spur of the exposed plateau. By now we should have been able to look down into Crater Lake, off to our east and 200 metres below. Normally a spectacular sight, today our visibility was down to 50 metres.

Nothing to see here. Just snow and our boot prints in the snow.

Crater Lake was named in 1905 for its likeness to a volcanic crater. Which it isn’t. It was formed by a valley glacier eroding a bowl-shaped trough some 60 metres deep. Crater Lake now occupies what was once a glacial cirque.

The lads were still bushy-tailed so we pushed on to a sheltered nook at Crater Peak (1270) metres. Here we took stock of the situation and decided it was risky continuing on over the now very cold, windy and exposed Cradle Plateau.

My minders, although well versed in this snow and ice stuff, were possibly thinking the old bloke wasn’t up to it anymore. Whatever the reason, it was a sensible decision to abandon ship… Read on to find out why….

Recent Incidents at Cradle Mountain

In the past year Tasmanian search and rescue have been on numerous callouts to rescue hikers in distress. Mainly it is bad luck, lack of preparation and just lack of experience that is causing the spike in rescues. Over the past winter/summer season, 200 helicopter rescues were needed in Tasmania, apart from all the ground rescues.

At Cradle Mountain specifically, a number of incidents played out over the year.

In late autumn a female tourist got lost on the Lake Wilks track and had to be rescued overnight. She was relying on her phone for navigation.

Mid-winter, a 52 year old male went missing and the search for him was abandoned. Presumed dead.

In early spring an incident involved a woman dying as her hiking group was ‘overwhelmed’ by the weather conditions. They required ground rescue after being assisted by a passing hikers. The group did not have appropriate equipment including a PLB.

Later in spring a man and woman suffering from mild hypothermia activated their PLB. While their equipment was suitable they underestimated the conditions and the effort required to cope with the weather.

What you should know: Advice from Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service

Two safety videos from Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service.

Summary…..

- The Cradle Mountain alpine zone can be unforgiving even for day walks.

- Many incidents involved inadequate preparation such as: no PLB; relying on mobile phones for navigation and communications; underestimating weather risks; underestimating terrain; inadequate clothing; overestimating fitness and ability.

- Don’t rely on helicopter rescue. Weather and terrain often make flying impossible. Ground extraction will always be hours away, so be proactive in trying to sort out your own problems.

- Casual hikers are most at risk.

But for us there was, as always with this mob, the important matter of a mid-morning feed. Taken standing up with our backs to the buffeting wind. Much like the long-horned shaggy Highland cattle we had seen grazing in paddocks on our way to Cradle Mountain.

Feed dispatched, we turned tail and headed for Waldheim, propelled off the snow-clad boardwalk with every fresh gust. Even my hiking poles gave no guarantee of staying firmly anchored on the boardwalk.

Back at the ranch we hoovered up a very late lunch and took off to check out Waldheim Museum, thence to the lower section of the Cradle Valley Walk. The homeward run would, hopefully, take us past herds of grazing wombats along Ronny Creek.

Waldheim

Set among the beech myrtles and King Billy pines of Cradle Valley is a replica of the original Waldheim Chalet built by German immigrant, Gustav Weindorfer. Gustav Weindorfer’s first trip to Cradle Valley was in 1909 with a naturalist friend, Dr Sutton. They attempted to climb Cradle Mountain but thick fog stymied their efforts.

Weindorfer returned in 1910 with his adventurous wife Kate and a Major R.E. Smith. This time they ascended Cradle Mountain. Here Weindorfer is said to have made that famous quote: ‘This must be a national park for the people for all time.’

Gustav and Kate purchased some land in Cradle Valley and built a guest chalet and home in 1912 and called it Waldheim, meaning ’forest home’. Built of King Billy Pine from nearby stands, it was opened for visitors. It featured a living room, a dining room and two bedrooms. The energetic Weindorfers enlarged the chalet, cleared and marked trails and named many of the features of the area.

In 1974 the chalet was destroyed by a bushfire. The current museum building is a replica of Waldheim constructed in 1976. But the Weindorfers left an indelible legacy for the world. As a result of their lobbying, in 1922, Cradle Mountain and Lake St Clair were gazetted as a Scenic Reserve. In the 1980s the area was recognised as part of the Tasmanian World Heritage Area.

Tuesday

A somewhat warmer morning at 4oC, with the sun and blue skies staging a comeback. As we still had time to squeeze in a morning walk before leaving for Hobart, we settled on a circuit of Dove Lake. There was the usual dissenting voter who opted to beetle off on a solo mission on the Cradle Valley Walk. Every family has one.

On a re-run of Sunday’s walk we took off towards the Dove Lake Walk via Ronny Creek.

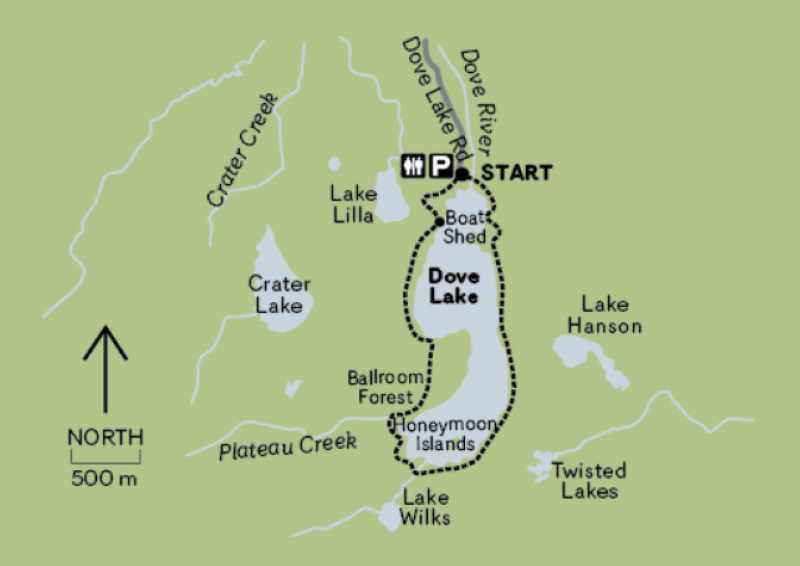

Map of Dove Lake Circuit

This time without the sheets of freezing rain. Soon after Ronny Creek the track climbs through what is loosely called ‘hummocky ground’.

Glacial Deposition

In fact, this hummocky ground is a belt of Pleistocene glacial deposition from the terminal moraines dumped by the Dove Valley glacier.

Hummocky ground is typically a chaotic micro-relief pattern of multitudinous small hummocks and low hills interspersed with undrained depressions holding swamps or ponds. This topography is technically called ‘kettling’.

Kettling formed along an active ice front or around masses of stagnant ice blocks from the Cradle Mountain glacier. The Ronny Creek topography likely formed during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM). Datings for the deposition of the Dove Valley moraines are between 22,000 and 17,000 years ago.

Glacial Erosion

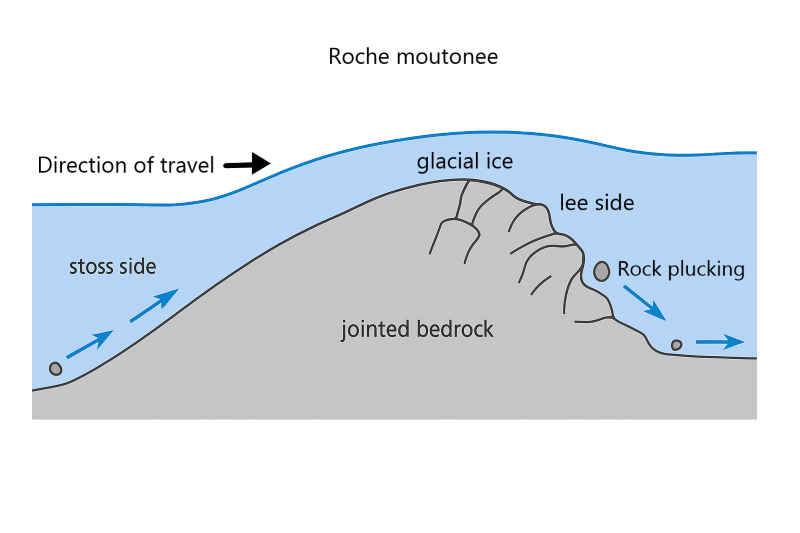

Soon after the belt of hummocky ground, the track steepens and passes into rockier terrain. Here one can find examples of landforms resulting from glacial abrasion of bare rock surfaces. Polished surfaces are the result of the passage of fine silt particles suspended in the basal ice. Examples of glacial striations, or scratches, in the bedrock were present but less frequently observed. Deeper striations or grooves are enlarged striations resulting from repeated channelling of basal debris along the same line.

The overall effect of abrasion is to smooth and round off bedrock in a process termed mammillation. I noticed these rounded surfaces faced upstream. Their orientation would be a good indicator of the direction of glacial flow.

As we climbed to the Lake Lilla outlet, I identified a number of larger scale landforms known as roche moutonees, rock sheep. Said in many textbooks to resemble recumbent sheep, but this etymology is disputed. Roche moutonees are humps of rock, smoothed on the upstream side by abrasion and with a steep lee slope resulting from glacial plucking as the glacier swept over the bedrock.

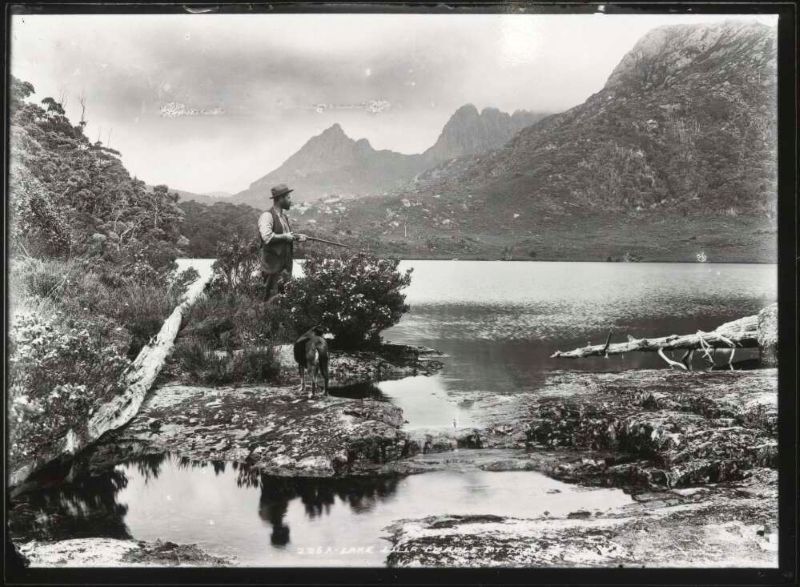

Lake Lilla and its big brother, Dove Lake, are cirque basins scoured out by glacial ice. With the retreat of the glacier these basins filled with water forming the two lakes. Lilla was Miss Lilla Spurling, youngest sister of Stephen Spurling, who named the lake in 1905.

Stephen Spurling was a pioneer of Tasmanian wilderness photography. He was the first of an outstanding line of fine Tasmanian wilderness photographers which includes the likes of Olegas Truchanas, Peter Dombrovskis, Rob Blakers, Cameron Blake and Hillary Younger.

After crossing the Lake Lilla outlet, the track climbs through a myrtle beech forest, Thrush Forest, before descending to the boathouse on the shores of Dove Lake, or alternatively to the Dove Lake Car Park. We chose the latter for our clockwise circumnavigation of Dove Lake.

Dove Lake consists of two deep interconnected basins. The southern downstream basin (50m) is a scour basin formed under the moving valley glacier where the bedrock was possibly softer and more shattered. A peninsula of hard quartzite rock separates this scour basin from the upstream cirque basin.

The upper basin was the Dove Valley cirque. A cirque is an armchair hollow at the head of a valley glacier where snow and ice accumulate. A cirque has a steep backwall which is eroded out by downward sliding ice. Dove Lake’s backwall rises some 400 metres up to the level of Little Horn at 1355 metres. The cirque section of Dove Lake is very deep, nearly 64 metres.

Meanwhile we crossed Dove River and headed south on our circumnavigation of the lake. It was named in 1905 by Weindorfer for a Mr Dove, an official of the Van Dieman’s Land Company.

The walking track takes you through a mix of terrains. Scrubby button grass gives way to sandy lake beaches, cascading waterfalls and dense rainforests on this loop trail.

Dove Lake itself is scenically outstanding especially when the wind isn’t howling across its surface. On a sunny day it is dark blue. The denser blue colouration the result of tinting from tea tree vegetation and button grass leaching into the water. From multiple points on the lakeside circuit, you can get brilliant photos of the lake and the snow-capped peaks in the background.

First stop, Suicide Rock. Oops… my new map shows a name change to Glacier Rock. This massive rock on the east coast of Dove Lake has a lookout and information boards to explain valley glaciers. Look carefully at the rock under your boots and you will see striations that run parallel to the length of the lake. This outcrop of hard quartzite withstood the erosive power of the Dove glacier.

The Dove Lake Circuit is an easy walk following the lake’s edge on good quality paths. On a sunny day like this it was an outstanding morning’s walk. Interestingly, it appears on old maps as the Truganini Track. But, again, that seems to have been erased from later maps.

Hordes of hiking tourists swept along the first kilometre but numbers thinned out the further we went. At the far end of the lake we bunkered down in a sheltered nook for a solitary morning tea. Couldn’t possibly miss out on Cheds, choc-coated licorice bullets and ginger chunks. Impressive mist-shrouded peaks loomed above.

Towards the northern end of the lake the track crosses the boggy outlet of Lake Wilks, another small cirque lake. If you look up, the peaks of Little Horn (1355m), Weindorfers Tower (1459m), Smithies Peak (1527m) and Cradle Mountain (1546m) rise spectacularly 500 metres vertically above you. Half a kilometre further on, and on the return leg, the path enters The Ballroom Forest, at the outlet of Plateau Creek.

The Ballroom Forest

This cool temperate rainforest is filled with ancient myrtle beech trees that are covered in moss. The rainforest floor is also covered in moss to give the whole scene a somewhat dank feeling. This rainforest is quite rare because these fire sensitive plants are usually destroyed when bushfires sweep across the area. But somehow this patch of the rainforest has survived.

After the Ballroom a somewhat rougher track climbs over the quartzite ridge separating the upper and lower basins of Dove Lake. From here it was a downhill trot back to the Boatshed and carpark. But we still had a few kilometres to trudge back to collect our car at Waldheim.

Then it was off to the Interpretation Centre to collect the renegade walker who we found lurking in the carpark. Just to be different, the trip back to our palatial Sandy Bay digs in Hobart took an alternative route via Mole Creek and thence to Deloraine for a late lunch.

As I recollect, curried beef pies featured on the menu. The eldest appeared clutching something healthy… a bread roll overflowing with goodies like lettuce and sprouts. Fillings that would appeal only to Peter Rabbit.

Hobart

Late afternoon, we snailed through central Hobart. Well timed to join a peak hour Tasmanian traffic snarl. But our holiday house at Sandy Beach for the next two nights was pretty spiffy. A room each. Bonus, no snoring boys .

Wednesday

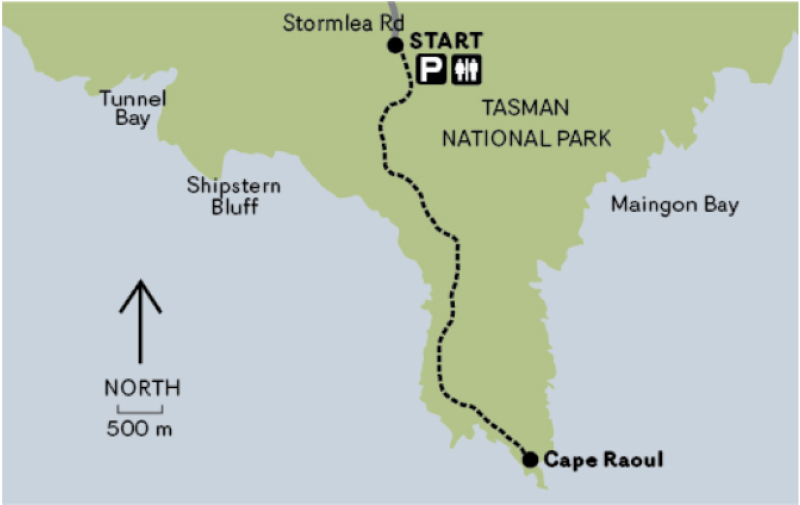

Our final full day in Tasmania. A brilliant blue sky and 21O C maximum. A welcome contrast to the previous three days. We pencilled in a foray to Cape Raoul on the southern tip of the Tasman Peninsula. The 14 kilometre return walk features dramatic dolerite sea cliffs, dry Eucalypt forest, patches of cool temperate rain forest and coastal heath.

Judging by the full carpark at the Cape Raoul track-head, the rest of Tasmania had decided to enjoy a rare sunny day in the bush too.

Cape Raoul: The Forgotten Cape

Cape Raoul was originally slated to be part of The Three Capes Track: Capes Raoul, Pillar and Hauy (Hoy). But, of course, it was just another casualty in the conga line of environmental vandalism, disasters and stuff-ups that seem to plague long suffering Tasmanians.

In the same camp as the Thylacine extinction, the Aboriginal wars, Atlantic salmon farms, the flooding of Lake Pedder, woodchipping, logging in the Tarkine, inoperable ferry terminals or the current $280 million AFL stadium own goal. Richard Flanagan should write a book about all this.

In the building of the Three Capes Track, it is rumoured that logistical issues and cost over-runs may have led to the dumping of the Cape Raoul section. The ‘Two Capes’ with its old bushwalkers’ pad has been seriously tizzied up with steps, a hardened M1 highway masquerading as a bushwalking track, lookouts, art installations and bench seats. Grandiose huts have been constructed to house tent-free Three Capes hikers.

The Tasmanian Parks Service describes the walk : “the 48-kilometre track has been designed as an achievable experience for a wide range of ages and abilities. It has been built to a dry-boot standard from a range of materials, including timbers, stone and gravel and is wide enough for two people to walk side-by-side.

The journey begins with walkers checking in at the Port Arthur Historic Site. You will then board a Pennicott Wilderness Journeys purpose built vessel for a cruise of up to 75 minutes exploring coves and the tallest sea cliffs in the Southern Hemisphere before delivering walkers to the start of the track at Denmans Cove. Over four days and three nights, walkers will cover the 48 kilometres amongst tall eucalypt forests, coastal heath and Australia’s highest sea cliffs.

Evenings are spent in warm and comfortable environmentally-sensitive cabins; Surveyors, Munro and Retakunna.”

I’m not sure about the ‘environmentally-sensitive’ claim. The footprint of multiple huts and associated infrastructure is hardly in keeping with the national park ethos of habitat preservation or low key experiences.

As one disgruntled bushwalker wrote: “It’s not a hike, it’s a hotel stay with long corridors”.

But, apart from the few bushwalking curmudgeons like myself, the Three Capes Walk is widely acclaimed in much of the hiking community and is usually fully booked out.

There is still a lingering rearguard action to the plethora of private lodge style “ecotourism” ventures sniffing around our national parks. And, quite obviously, I’m not a fan of these private lodges or any overblown infrastructure in our national parks. But most of my acquaintances seem unfazed. The argument usually trotted out is that any development that gets people out in nature must be a good thing. QED.

If you happen to care about the commercialisaton our national park estate, check out the links below:

- Josh Hamill: The Slow Death of Australian Wilderness in his Better Hiking website.

- James Mc Cormack, Editor of Wild Magazine: Luxury Lodges means Wilderness Lost.

- James Mc Cormack, Editor of Wild Magazine: Luxury Lodges means Wilderness Lost. Part 2.

- Bushwalking NSW. Tourist development in protected areas. Analysis by John Souter.

While I fully support the concept of encouraging people to be out and about in our national parks, I have some fundamental reservations about what is happening:

- The incursions of private lodges and huts into our national parks.

- The overkill in the construction of tracks with widening and hardening.

- The excessive footprints and glamping up of publicly owned huts.

- The cost of walking some of these ‘Great Walks’ .

The Tasmanian National Parks Association suggested an alternative to the Three Capes Walk ( called the Tasman Trail) which linked existing tracks from Waterfall Bay in the north to Cape Pillar in the south. A bloody good proposal if you want my opinion. I’ve walked it.

The Three (Two) Capes project was opened for business in 2016. And it is a good business that attracts heaps of walkers. Good for its operators …. less so for cash-strapped taxpayers, some of whom will never be able to afford to use the huts on the Three Capes Track.

Contrast this with the egalitarian approach to huts and tracks in New Zealand. For a modest outlay all trampers are welcome to use the extensive, but basic, hut network. Nothing smick, but more than adequate shelter from the elements.

Meanwhile, back in Tasmania, hand over a fistful of shekels and you can walk the Three Capes track for the tidy sum of $600.00 per person, self-guided. A self-guided family (2 adults, 2 children) would need to shell out a cool $2210.00. But you can get an inner glow from knowing that your dollars are helping the Tasmanian Walking Company (TWC) pay for some of its advertising budget via a cack-handed agreement for the Tassie government to pay for some TWC media.

In an estimates committee meeting of the Tasmanian Parliament in June 2022, a government official owned up to payments totalling $361,000 of taxpayers’ dosh going to TWC for ‘marketing reimbursement‘ since 2018.

Well-heeled hikers, of whom there appears no shortage, can opt for a plush guided Three Capes Wilderness Experience with the TWC who the Tassie government has designated as the sole operator. Prices range between $3000 to $4000 for four nights. Inclusions are overnighting in luxury private lodges, gourmet meals, beverages, hot showers, massages and spas.

Some blurb from the TWC on their Signature Walk suggests that ‘… your pace might quicken in the knowledge there is a massage, facial or plunge bath on offer at Cape Pillar Lodge.‘ Tough stuff this hiking lurk. But sign me up as I inexorably slide into my eighth decade.

State governments all over Australia are joining the hiking gold rush, hatching similar ecotourism projects to transfer prime national park estate to the ecotourism spivocracy to turn a quick buck. Western Australia is, at present, the standout exception with very significant upgrades to park facilities for all people to enjoy. Not just those with deep pockets. Well done WA.

Elsewhere in Australia, park facilities are often handed over for peanuts in woeful commercial-in-confidence deals. The target demographic according to Brett Godfrey, CEO TWC, in an interview with the ABC was : ‘a 52 year old single female who finds going into the wilderness not her cup of tea’. I assume he was just kidding. The TWC model of bushwalking does seem to be a very popular and safe option.

A far cry from bushwalking in the days of yore when bushwalking could be hard yakka. But self-organised, egalitarian, family friendly, and affordable.

In my biased and humble opinion, bushwalkers then were definitely more stoic and independent. I did this walk way back in 2010 as a three day 40 kilometre walk from Fortesque Bay out to Cape Pillar and back via Cape Hauy. No guides, grand huts, hot showers and spas then.

At the time I wrote in my journal: “Here is a landscape of coastal grandeur, of natural and cultural richness unsurpassed. For the bushwalker the Tasman Peninsula is a ‘must do’, the possible discomfort of pelting rain and and gale force winds as the track winds along the edge of massive cliff lines adding a modicum of spice to an otherwise easy 40 kilometre walk.”

On reflection, maybe it is easy to understand why today’s hikers might vote with their wallets and relax in a heated lounge with their drinkies before retiring under a cosy doona /sleeping bag.

Meanwhile, back at the Cape Raoul track head we followed the wide, manicured path that climbs two kilometres through open Eucalypt forest. The dominant trees are Silver peppermint (E. tenuiramis), Black peppermint (E. amygdalina) and White stringybark (E. obliqua). A dense understorey clothed the slopes. A few of the understorey plants that looked vaguely familiar were Native fuschia (Correa reflexa), Hop bush (Dodonaea viscosa), Bottlebrush (Banksia marginata) and a Prickly heath (Epacaris impressa).

Map of Cape Raoul Walking Track

The forest opens out finally at the cliff’s edge at Cape Raoul Lookout. Here we had impressive views of Cape Raoul projecting far out into Raoul Bay. The famous dolerite-cliffed coastline dropped 400 metres into the clear blue waters of the bay.

Cape Raoul was named in 1792 by the French mariner D’Entrecasteaux after the pilot for his expedition, Jean Francois Raoul.

By now the inexorable march of time caught up on us, so we headed off to the Ship Stern Lookout for a peekaboo in the other direction.

The Ship Stern track cuts westward from the Cape Raoul track. After a kilometre the track leads out to Ship Stern Lookout. The Ship Stern is a truncated bluff of glaciomarine sediments and also home to one of Australia’s famous large wave surfing breaks.

Waves here reach up to 9 metres, smashing down onto a rocky wavecut platform bounding Ship Stern. This notoriously dangerous wave break attracts surfers from around the world. Sensibly, they often opt to be towed through the swash zone on jet-skis, which we could see operating today.

In 2017 a huge chunk of the bluff collapsed, but that wasn’t unusual. A few years previously a car-sized boulder fell out of the cliff as walkers passed underneath. Suffice to say we saw no walkers or surfers mooching around on the platform today.

Ship Stern is a truncated headland with a fringing wave cut platform. The headland is not dolerite, but Late Carboniferous to Triassic glaciomarine sediments some 250-290 million years old. These sediments are predominately pebbly mudstones, sandstones and layers of limestone. One can find dropstones in the glacial layers. The presence of dropstones is a definitive indicator of glacial deposition.

These glacial deposits are much older than the Pleistocene glaciated landscapes that we had seen on the Central Plateau or Cradle Mountain. They are the consequence of an ice cap that covered Tasmania during a prolonged cold phase known as the Late Palaeozoic Ice Age, aka Late Palaeozoic Icehouse, some 360-255 million years ago. This was the longest and most extensive ice age in the Earth’s geological history but centred on the southern super-continent of Gondwana.

Back at the carpark, those Phar Laps of the track and trail were waiting patiently for the old nag to show up. A short road trip took us to the Lucky Ducks Café in Nubeena for a final celebratory feed. The food was delicious and we were seated near the large windows giving views across Parsons Bay. I ordered the lunch special, curry with steamed rice and local greens. The lads went traditional: chips and salad with fresh local fish (caution: see below) and lamb burgers.

But if you peer across the placid waters of Parsons Bay, you will see fish pens floating in the bay. These are but a small part of Tasmania’s increasingly infamous salmon farming industry. News services report on mass salmon deaths and“great globules of fatty fish flesh” washing up on Tassie’s ‘pristine beaches’.

Data from the Tasmanian Government’s EPA revealed that four million salmon died prematurely in Tasmanian Salmon Farms in 2025, with 500,000 fish dying in November and December alone. In Norway, mass fish deaths can attract big fines. Aquaculture company Salaks copped a fine of A$286,000 for salmon deaths in November 2025. Tasmania has no equivalent legislation to hold salmon producers to account. Enjoy your swim and feed of farmed Atlantic salmon.

Atlantic Salmon farming is just another in Tasmania’s long line of environmental horror stories. Just ask Richard Flanagan, Tassie author and winner of Man Booker Prize. Flanagan has written a book about Salmon Farming in Tasmania: ‘ Toxic: The rotting underbelly of the Tasmanian Salmon Industry’.

With bulging bellies these lucky ducks headed back to our digs via the Cascade Brewery (est.1824) for a tankard or two. Except the chauffeur.

Late afternoon, back in Sandy Bay, eldest and youngest sons shrugged off my dire warnings about fatty fish balls and took the Polar Plunge into the frigid waters of the Derwent Estuary as their farewell salute to our Tassie adventure. We would all fly home to our respective states on the morrow.

And I must say it was a pleasure to share another Tassie adventure with my three sons. Every dad should be so lucky.